Pago Pago, American Samoa

Pago Pago | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Nicknames: O le Maputasi ("The Single Chief's House") | |

| Coordinates: 14°16′26″S 170°42′16″W / 14.27389°S 170.70444°W | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Island | Tutuila |

| District | Eastern |

| County | Maoputasi |

| Became Capital | 1899 |

| Named for | Pago Volcano |

| Government | |

| • Body | Village Council |

| • Mayor | Pulu Ae Ae |

| Area | |

• Village | 8.85 km2 (3.42 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 653 m (2,142 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Village | 3,000 |

| • Density | 412.5/km2 (1,068/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 15,000 |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Samoa Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799[1] |

| Area code | +1 684 |

| Climate | Af |

| FIPS code | 60-62500 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1389119[2] |

| Website | pagopago |

| |

Pago Pago (/ˈpɑːŋɡɔːˈpɑːŋɡɔː/ PAHNG-gaw-PAHNG-gaw; Samoan: Samoan pronunciation: [ˈpaŋo ˈpaŋo])[3] is the capital of American Samoa. It is in Maoputasi County on Tutuila, the main island of American Samoa.

Pago Pago is home to one of the deepest natural deepwater harbors in the South Pacific Ocean, sheltered from wind and rough seas, and strategically located.[4][5]: 52 [6]: 12 The harbor is also one of the best protected in the South Pacific,[7]: 11 which gives American Samoa a natural advantage because it makes landing fish for processing easier.[7]: 61 Tourism, entertainment, food, and tuna canning are its main industries. As of 1993, Pago Pago was the world's fourth-largest tuna processor.[8]: 353 In 2009, the total value of fish landed in Pago Pago — about $200,000,000 annually — is higher than in any other port in any U.S. state or territory.[9] It is home to the largest tuna cannery in the world.[10][11][12]

Pago Pago is the only modern urban center in American Samoa[6]: 29 [13] and the main port of American Samoa.[14][15][16] It is also home to the territorial government, all the industry, and most of the commerce in American Samoa.[17]: 166 The Greater Pago Pago Metropolitan Area encompasses several villages strung together along Pago Pago Harbor.[18][19] One of the villages is itself named Pago Pago, and in 2010, that village had a population of 3,656. The constituent villages are: Utulei, Fagatogo, Malaloa, Pago Pago, Satala and Atu'u. Fagatogo is the downtown area, referred to as "town", and is home to the legislature, while the executive seat is in Utulei. Also in Fagatogo are the Fono, police department, the Port of Pago Pago, and many shops and hotels. In 2000, the Greater Pago Pago area was home to 8,000 residents;[20] by 2010 the population had increased to 15,000.[21]

Rainmaker Mountain (Mount Pioa), located near Pago Pago, contributes to a weather pattern that results in the city having the highest annual rainfall of any harbor in the world.[22][23][24] It stands protectively over the eastern side of Pago Pago, making the harbor one of the most sheltered deepwater anchorages in the Pacific Ocean.[25]: 3

Historically, the strategic location of Pago Pago Bay played a direct role in the political separation of Western and Eastern Samoa. The initial reason that the U.S. was interested in Tutuila was its desire to use Pago Pago Harbor as a coaling station.[26]: 30–31 The town has the distinction of being the southernmost U.S. capital, and the only one located in the Southern Hemisphere.

Etymology and pronunciation

[edit]The origin of the name Pago Pago is uncertain. One hypothesis suggests that it is derived from the Samoan language, where it is interpreted to mean "place of prayer."[27]

The letter "g" in Samoan sounds like "ng"; thus Pago Pago is pronounced "pahngo pahngo."[28][29][30][31][32][33]

An early name for Pago Pago was Long Bay (Samoan: O le Fagaloa), which was a name used by the first permanent inhabitants to settle in the Pago Pago area.[26]: 26 [34][35]: 123 It was also called O le Maputasi ("The Single Chief's House") in compliment to the Mauga, who lived at Gagamoe in Pago Pago and was the senior to all the other chiefs in the area.[35]: 123

For a brief period in the 1830s, Pago Pago was also known as Cuthbert's Harbor, named after British Captain Cuthbert, who was the first European to enter Pago Pago Harbor.[36]

History

[edit]Pago Pago was first settled 4,000 years ago.[37] The area was initially settled by Polynesian navigators, who established a vibrant community rooted in agriculture, fishing, and the distinct cultural practices of Samoan society.[27] There is archeological evidence of people living in the Pago Pago Valley at least 1500–1300 years ago.[38] The ancient people of Tutuila produced clay pottery known as Samoan Plainware. The majority of these open bowls had plain designs and featured rounded bases. Such pottery has been retrieved from sites in Pago Pago, including at Vaipito. The production of such pottery ceased approximately 1500 years ago.[39][40] A site in the Vaipito Valley has also revealed more substantial elements, such as constructions made from rocks, like house foundations and terraces (lau mafola).[41][42]

Ceramic findings have been retrieved at Vaipito, an inland area within Pago Pago village. A deposit here is thought to be an old hill-slope below a living area where people threw away their waste. Numerous large ceramic pieces have been retrieved here. The layer with the ceramics dates back to the time between 350 BCE and 10 CE. Another site, Fo’isia, is located approximately 100 meters from Vaipito, at the same elevation inland in Pago Pago. During sewer line construction, the American Samoa Power Authority noticed many broken pieces of clay pottery. Five dates associated with the ceramics indicate a time range between 370 BCE and 130 CE.[43]

Tongan rule

[edit]The island of Tutuila was part of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire from the invasion around 950 CE to when Tongans were expelled in 1250. According to Samoan folklore, a warrior from Pago Pago, Fua’au, is associated with driving the Tongans out of Tutuila. According to the legend, Fua’au's fiancé, Tauoloasi’i, was kidnapped and taken to Tonga while sleeping on an exquisite mat known as Moeilefuefue. Filled with anger at the loss of his fiancé and the renowned mat, Fua’au rallied the Tutuilans, encouraging them to revolt against the Tongan rule imposed by Lautivunia.[44][45]

During the period of Tongan rule, political opponents and defeated Samoan warriors were exiled to Pago Pago. The surrounding settlements effectively functioned as a Samoan penal colony. In response to the oppression, the Samoans, under the leadership of paramount chief Malietoa, eventually revolted against their Tongan rulers.[46] According to one source, it was Chief Fua’autoa of Pago Pago who successfully expelled the Tongans from Pago Pago.[47]

Old Pago Pago

[edit]Until 1722, Pago Pago, like several other villages in American Sāmoa such as Fagasā and Vatia, existed as a ridge-top settlement. This upland community, now part of the National Park of American Sāmoa, was strategically situated to provide safety during a period marked by inter-island conflicts involving Sāmoa, Fiji, Tahiti, and Tonga. The elevated location offered protection from coastal raids, as attackers arriving by boat posed a significant threat to shoreline settlements. By 1772, the majority of families had relocated from the highlands to the coast, establishing new homes near the shoreline. However, oral histories indicate that a few households continued to reside or farm in the upland areas into the late 19th century. Archeological findings at the site of Old Pago Pago include ancient rock walls, building foundations, and graves. Some of these graves are believed to belong to chiefs or ceremonial figures, such as a taupou (a ceremonial maiden), with legends suggesting one may have been interred in a bonito boat. The remnants of Old Pago Pago are accessible via the Mount ‘Alava Trailhead at Fagasā Pass, just west of Vaipito Valley.[48]

When Westerners first visited Tutuila, the Mauga was the leading matai (chief) of Pago Pago.[49]

19th century

[edit]

In 1791, Captain Edward Edwards, leading the British warship HMS Pandora in the pursuit of the Bounty mutineers, arrived at Pago Pago Harbor. During their search, the crew stumbled upon a French military uniform belonging to one of Pérouse’s men, who had been killed at Aʻasu in 1787.[50][51]

In 1824, Otto von Kotzebue is believed to have discovered the entrance to Pago Pago Harbor, according to one source.[52]

In 1836, the English whaler Elizabeth, captained by Cuthbert, became the first European vessel to enter Pago Pago Harbor. Captain Cuthbert is credited with ‘discovering’ Pago Pago and naming it Cuthbert Harbor.[53]

In the 1830s, two missionaries were assigned to Tutuila Island: Reverend Archibald W. Murray and his wife to Pago Pago and Reverend Barnden to Leone. They landed at Fagasa Bay and hiked over the hill to the High Chief Mauga in Pago Pago. Mauga welcomed the missionaries and gave them support. RMS Dunottar Castle later moved to Pago Pago, becoming the second ship to enter Pago Pago Harbor.[25]: 79–80 Under the auspices of Maunga, Murray established a wooden residence in Pago Pago, where he endeavored to exemplify Christian living.[54][55]

In 1834, Matthew Hunkin arrived in Pago Pago and served as a companion to Archibald Murray, both residing under the patronage of High Chief Mauga. Together, they conducted visits to villages situated along the eastern end of Tutuila. Subsequently, both men relocated to Leone, where Murray undertook preparations to establish the Mission Institute for Pacific Islanders at Fagatele, situated on the outskirts of the Leone village.[56]

Beginning in 1836, whaling vessels started calling at Pago Pago Harbor, quickly transforming it into a favored stopover. Crews found it to be a secure place to rest, take on supplies, and carry out repairs. As of 1866, whalers no longer visited the Samoan Islands as whaling activities had shifted farther north.[57]

In 1837, Tutuila’s chiefs and Captain Charles Bethune of H.M.S. Conway reached an agreement on Pago Pago’s first documented commercial port regulations, finalized on December 27 of that year.[58][59]

On May 9, 1838, the London Missionary Society established a church in Pago Pago.[60][61][62]

In 1839, the Sāmoan Islands experienced its first recorded epidemic, which resulted in the death of High Chief Mauga of Pago Pago. After his passing, Manuma assumed the title.[63][64] After the death of his stepbrother Pomale, Manuma provoked controversy within the Christian community by eloping with Pomale's widow. As a result, the aiga deposed him from his position. Nevertheless, Manuma was later reinstated, and he presided as the Mauga of Pago Pago until his death in 1849.[65]

As early as 1839, American interest was generated for the Pago Pago area when Commander Charles Wilkes, head of the United States Exploring Expedition, surveyed Pago Pago Harbor and the island. Wilkes' favorable report attracted so much interest that the U.S. Navy began planning a move to the Pago Pago area. During his time in Pago Pago, Wilkes negotiated a set of “Commercial Regulations” with the matais of Pago Pago under the leadership of Paramount Ali'i Mauga. Wilkes' treaty was never ratified, but captains and Samoan leaders operated by it.[66] Rumors of possible annexation by Britain or Germany were taken seriously by the U.S., and the U.S. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish sent Colonel Albert Steinberger to negotiate with Samoan chiefs on behalf of American interests.[67] American interest in Pago Pago was also a result of Tutuila's central position in one of the world's richest whaling grounds.

On August 8, 1844, Archibald Wright Murray wrote a letter recounting how the Tutuilans, at one point, prepared to vacate their settlements and negotiate with the French while taking refuge in the highlands. Recognizing Pago Pago Harbor as the island’s most significant lure for European powers, they planned to cede it to France in return for a pledge safeguarding Tutuila’s independence.[68]

In 1871, the local steamer business of W. H. Webb required coal and he sent Captain E. Wakeman to Samoa in order to evaluate the suitability of Pago Pago as a coaling station. Wakeman approved the harbor and alerted the U.S. Navy about Germany's intent to take over the area. The U.S. Navy responded a few months later by dispatching Commander Richard Meade from Honolulu, Hawaii to assess Pago Pago's suitability as a naval station. Meade arrived in Pago Pago on USS Narragansett and made a treaty with the Mauga for the exclusive use of the harbor and a set of commercial regulations to govern the trading and shipping in Pago Pago. He also purchased land for a new naval station.[25]: 137–138 High Chief Mauga of Pago Pago stated his wish for the village to be recognized as Tutuila Island’s capital.[69]

In 1872, the chief of Pago Pago signed a treaty with the U.S., giving the American government considerable influence on the island.[70] It was acquired by the United States through a treaty in 1877.[71] One year after the naval base was built at Pearl Harbor in 1887, the U.S. government established a naval station in Pago Pago.[72] It was primarily used as a fueling station for both naval- and commercial ships.[73]

During the Tutuila War of 1877, all buildings in Pago Pago were destroyed. The war emerged during a tumultuous period, where Samoans were sharply divided over the future direction of their government. In response to the growing threat posed by the Puletua — a rising opposition faction — the Samoan leadership based in Apia sent Mamea to Washington, D.C. to negotiate an agreement with the U.S. While Mamea was abroad, the Puletua launched a rebellion, escalating the situation into full-scale war in Tutuila. To regain control, government forces stationed in Leone advanced toward Pago Pago, where the rebel leader Mauga was headquartered. The troops burned every building in Pago Pago and pursued Mauga along with several hundred followers to Aunu’u Island. The Puletua faction on Tutuila, led by the former U.S. Consul to Sāmoa, S. S. Foster, who had moved to Pago Pago after his dismissal, and Mauga, found Aunu’u incapable of supporting their forces. Consequently, they returned to Tutuila where they soon surrendered.[74][75]

In 1878, the U.S. Navy first established a coaling station, right outside Fagatogo. The United States Navy later bought land east of Fagatogo and on Goat Island, an adjacent peninsula. Sufficient land was obtained in 1898 and the construction of United States Naval Station Tutuila was completed in 1902. The station commander doubled as American Samoa's Governor from 1899 to 1905, when the station commandant was designated Naval Governor of American Samoa. The Fono (legislature) served as an advisory council to the governor.[76]: 84–85

Despite the Samoan Islands being a part of the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany maintained a strong naval presence in the area. Twice between 1880 and 1900, the U.S. Navy came close to taking part in a shooting war while its only true interest was the establishment of a coaling station in Pago Pago. The U.S. quietly purchased land around the harbor for the construction of the naval station. It rented land on Fagatogo Beach for $10/month in order to store the coal. Admiral Lewis Kimberly was ordered to Pago Pago while in Apia waiting for transportation home after the hurricane of 1889. In Pago Pago, he selected a site for the new coaling station and naval base. In June 1890, the U.S. Congress passed an appropriation of $100,000 for the purpose of permanently establishing a station for the naval and commercial marine. With the appropriation, the State Department sent Consul Harold M. Sewall from Apia to Pago Pago to buy six tracts of land for the project. Some parts were previously owned by the Polynesian Land Company, while other tracts were still owned by Samoan families. For the defense of the harbor in event of a naval war, the U.S. Navy wanted to purchase headlands and mountainsides above the Lepua Catholic Church which directly faced the harbor's entrance.[25]: 138–139

In 1883, a conflict began at Pago Pago Bay between Mauga Lei and Mauga Manuma. The dispute revolved around the entitlement to the title "Mauga". Mauga Lei's actions led to widespread dissatisfaction among the residents of Fagatogo and Aua, culminating in the Taua o Sa’ousoali'i conflict. The residents of Fagasā joined Pago Pago village in an effort to overthrow Mauga Lei and support Manuma. The uprising forced Mauga Lei's forces to Aunuʻu. Mauga Lei, who had a close friendship with King Malietoa Laupepa, secured intervention through two warships to resolve the hostilities. Intervention came in the form of a peace mission led by HMS Miranda, under Captain William A. Dyke Acland, and supported by the German gunboat SMS Hyäne. Both Mauga Lei and Mauga Manuma were summoned to a peace conference aboard the HMS Miranda. Both initially resisted boarding the ship but eventually relented after diplomatic pressure. The agreement that followed emphasized reconciliation and required both parties to disarm publicly.[77][78] The conflict led to the deaths of 12 people.[79]

In 1887, the Kaimiloa, a 171-ton steamer and the only warship in the fleet of King Kalākaua of Hawai‘i, was sent on a diplomatic mission to the Sāmoan Islands as part of the Hawaiian monarch's initiative to create a united Polynesian kingdom. The journey included visits to several key locations, including Pago Pago, which was an important trading hub at the time. Historical accounts document the trade of the Kaimiloa's cannons to the Samoans, with at least one of these cannons now preserved and on display at the Jean P. Haydon Museum.[80][81]

In 1889, Robert Louis Stevenson paid a visit to Pago Pago.[82]

On May 27, 1893, a branch of the LDS Church was established in Pago Pago. The church had first arrived on the island in 1863 and became formally organized on Tutuila in 1888.[83]

In 1898, a California-based construction and engineering firm was contracted to build the coal depot. The naval engineer in charge was W. I. Chambers. On April 30, 1899, Commander Benjamin Franklin Tilley sailed from Norfolk, Virginia on USS Abarenda with a cargo of coal and steel for the project. The U.S. Navy was the only American agency present in the area, and it was made responsible for administering the new territory.[25]: 139–140

In 1899, Pago Pago became the administrative capital of American Samoa.[84][85] Pago Pago and Tutuila Island were formally part of the Kingdom of Samoa until 1899, when they became U.S. territory.[86][87]

On April 17, 1900, the first American flag was raised at Sogelau Hill above the site of the new wharf and coaling facilities in Fagatogo. For the ceremony, a group of invitees from Apia arrived with German Governor Heinrich Solf onboard SMS Cormoran. USS Abarenda, home of B. F. Tilley and his new government, was in the harbor. American consul Luther W. Osborn arrived from Apia, and many spectators arrived from American Samoa villages and other countries. Tilley was the master of ceremonies and began the program by reading the Proclamation of the President of the United States, which asserted American sovereignty over the islands. Next was the reading of the Order of the Secretary of the Navy, followed by chiefs who read the Deed of Cession, which they had written and signed. Before raising the flag, reverend E. V. Cooper of the London Missionary Society (LMS) and reverend Father Meinaidier of the Roman Catholic Mission offered prayers. Students from the LMS school in Fagalele sang the national anthem. The two ships, Comoran and Abarenda, fired the national salutes.[25]: 145–146 [26]: 111 The Deed of Cession of Tutuila and Aunu'u Islands was signed on Gagamoe, and formalized the relationship between the U.S. and American Samoa. Gagamoe is an area in Pago Pago which is the Mauga family's communal and sacred land.[88][89]

20th century

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pago Pago became American Samoa's port of entry.[35]: 179

On April 11, 1904, the first public school in American Samoa, called Fagatogo, was established in the naval station area. The school had two teachers and forty students at the time of its opening.[90]

From December 16, 1916, to January 30, 1917, English author W. Somerset Maugham and his secretary and lover, Gerald Haxton, visited Pago Pago on their way from Hawai'i to Tahiti. Also on board the ship was a passenger named Miss Sadie Thompson, who had been evicted from Hawaii for prostitution. She was later the main character in the popular short story, Rain (1921), a story of a prostitute arriving in Pago Pago.[91] Delayed because of a quarantine inspection, they checked into what is now known as Sadie Thompson Inn. Maugham also met an American sailor here, who later appeared as the title character in another short story, Red (1921).[84][92] The Sadie Thompson Inn was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 2003.

In 1920, Mauga Moi Moi, the highest ranking chief of Pago Pago, initiated the Mau movement.[93]

First and Second World Wars

[edit]In May 1917, when the U.S. joined World War I, two German ships anchoring in Pago Pago were seized. The 10,000-ton Elsass was towed to Honolulu and turned over to the U.S. Navy, while its smaller gunboat, Solf, was refitted in Pago Pago and given the name USS Samoa. Wireless messaging between Pago Pago and Hawaii was routed through Fiji. As the British censored all messages through Fiji, the Navy quickly upgraded the facilities to go directly between Pago Pago and Honolulu.[25]: 188

On January 10, 1938, the flying boat Samoan Clipper exploded just after leaving Pago Pago Harbor. Pilot Edwin Musick and his crew of six died in the accident.[94][95]

Pago Pago was a vital naval base for the U.S. during World War II.[96] Limited improvements at the naval station took place in the summer of 1940, which included a Marine Corps airfield at Tafuna. The new airfield was partly operational by April 1942, and fully operational by June. On March 15, 1941, the Marine Corps' 7th Defense Battalion arrived in Pago Pago and was the first Fleet Marine Force unit to serve in the South Pacific Ocean. It was also the first such unit to be deployed in defense of an American island. Guns were emplaced at Blunts and Breakers Points, covering Pago Pago Harbor. It trained the only Marine reserve unit to serve on active duty during World War II, namely the 1st Samoan Battalion, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. The battalion mobilized after the attack on Pearl Harbor and remained active until January 1944.[76]: 85–86

In January 1942 Pago Pago Harbor was shelled by a Japanese submarine, but this was the only battle action on the islands during World War II.[97] On January 20, 1942, the 2nd Marine Brigade arrived in Pago Pago with about 5,000 men and various supplies of weaponry, including cannons and tanks.[98]

On August 24, 1943, Pago Pago and the U.S. Naval Station was visited by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[99][100]

On October 7, 1949, the USS Chehalis, a World War II oil and gas tanker, exploded and sank in Pago Pago Harbor. It remains the only shipwreck from that era found in the harbor and lies just over 100 feet beneath the current fuel dock. Measuring 90 meters in length, the wreck continues to be considered a source of pollution impacting the water quality as of 2002.[101][102]

1960s

[edit]Pago Pago was an important location for NASA's Apollo program from 1961 to 1972. Apollo 10, Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 13, Apollo 14 and Apollo 17 landed by Tutuila Island, and the crew flew from Pago Pago to Honolulu on their way back to the mainland.[103][104] At Jean P. Haydon Museum are displays of an American Samoa-flag brought to the Moon in 1969 by Apollo 11, as well as moonstones, all given as a gift to American Samoa by President Richard Nixon following the return of the Apollo Moon missions.[105] The museum was officially opened in October 1971 with an opening featuring Margaret Mead as a guest speaker. The National Endowment for the Arts provided a start-up grant. The most valuable asset was an exquisite mat reputed to be the Fala o Futa, the first important fine mat of Samoa, donated by Senate President HC Salanoa S.P. Aumoeualogo. The other major contribution was a cannon which came off Kaimiloa, a 171-ton steamer and the only warship in the fleet of King Kalakaua of Hawai'i. The Hawaiian king sent the ship to the Samoan Islands in an effort at creating a Polynesian kingdom.[25]: 313

In 1965, the Tramway at Mount ʻAlava was constructed as access to the TV transmission equipment on the mountain. It ran from atop Solo Hill at the end of the Togotogo Ridge above Utulei. It ascended 1.1 miles (1.8 kilometers) across Pago Pago Harbor and landed at the 1,598 ft (487 m) Mount ʻAlava. It was one of the world's longest single-span cablecar routes.[17]: 167 [106]: 475 [107]

President Lyndon B. Johnson and First Lady Lady Bird Johnson visited Pago Pago on October 18, 1966. Johnson remains the only U.S. president to have visited American Samoa. Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medical Center was named in honor of the president.[108] Landing ahead of the Air Force One was the press plane that carried seventy news reporters. The two-hour visit was televised throughout the country and the world. Governor H. Rex Lee and traditional leaders crammed ceremonies, entertainment, a brief tour, and a school dedication: the Manulele Tausala, Lady Bird Johnson School. The President gave a speech where he laid out the American policy for its lone South Pacific territory. The President and First Lady returned to American Samoa in December 1966, on their way to Prime Minister's Harold Holt's funeral in Australia. Governor Owen Aspinall offered a quiet welcome as the White House asked for there to be no ceremonies during the visit. Around 3,000 spectators went to the Pago Pago International Airport to see the President.[25]: 292

In May 1967, Governor H. Rex Lee signed a law making Pago Pago a duty-free port. Excise taxes, however, were imposed on automobiles, firearms, luxury goods, and auto parts. The excise tax was heaviest on secondhand motor vehicles and machinery. It was nicknamed the "Junk Bill" as it intended to keep out old used merchandise.[25]: 285

1970s and later

[edit]In November 1970, Pope Paul VI visited Pago Pago on his way to Australia.[109][25]: 292

Shortly after Christmas in 1970, a village fire destroyed the legislative chambers and adjacent facilities. It was decided that the new Legislature would be placed permanently in the center of the township of Fagatogo, the traditional Malae o le Talu, at a cost of $500,000. A triple celebration in October 1973 marked the dedication of the new Fono compound, its 25th anniversary, and the holding in Pago Pago of the Pacific Conference of Legislators. First Lady Lillian "Lily" Lee unveiled the official seal of American Samoa carved on ifelele by master wood-carver Sven Ortquist, which was mounted in front of the new Fono. The Arts Council Choir sang the territorial anthem, "Amerika Samoa", as composer HC Tuiteleleapaga Napoleone conducted. The territorial bird, lupe, and flower, mosooi, were officially announced during the same ceremony.[25]: 302

Shipping in and out of Pago Pago experienced an economic boom from 1970 to 1974. Flights into Pago Pago International Airport continued to increase in the early 1970s, with the Office of Tourism reporting 40,000 visitors and calling for the construction of additional hotels. Service to American Samoa by air was offered by Pan American (four weekly flights), Air New Zealand (four weekly flights), and UTA (four weekly flights). From 1974 to 1975, records show that 78,000 passengers moved by air between the two Samoas and that Polynesian Airlines collected $1.8 million from the route.[25]: 311 Pago Pago Harbor became a popular stop for yachts in the early 1970s.[25]: 312

In 1972, Army Sp. 4 Fiatele Taulago Teʻo was killed in Vietnam and his body was flown home to Pago Pago where his many awards were presented to his parents. The first Army Reserve Center was named after him.[25]: 316 Two additional American Samoans were killed in the Vietnam War, Cpl. Lane Fatutoa Levi and LCpl. Fagatoele Lokeni in 1970 and 1968, respectively.[110]

In 1972, seven historical buildings in American Samoa were entered in the National Register of Historic Places of the United States, including Navy Building 38, Jean P. Haydon Museum, and the Government House.[25]: 313

In 1985, the decision was made to privatize Ronald Reagan Shipyard. Southwest Marine, a company from San Diego, California, was selected to operate the shipyard under lease from the American Samoa Government.[111]

In 1986, the First Invitational Canoe Race was held in Pago Pago.[25]: 339

On September 25, 1991, downtown Fagatogo received a new landmark: the Samoa News Building. The Executive Office Building in Utulei was dedicated on October 11, 1991.[25]: 357

In 1999, the first international conference on the Samoan language was held in Pago Pago.[112]

21st century

[edit]

Since 2000, American Samoa Department of Education through its school athletic program is the host of the East & West High School All-Star Football Game. It has been held at the field in Gagamoe in Pago Pago.[113]

In 2008, the tenth Festival of Pacific Arts was held in Pago Pago, drawing 2,500 participants from 27 countries.[114] Also in 2008, Asuega Fa’amamata, one of the few female chiefs in the territory, was elected by Pago Pago as its new senator, becoming the sole female legislator in the American Samoa Fono.[115]

In 2010, Tri Marine Group, the world's largest supplier of fish, purchased the plant assets of Samoa Packing and committed $34 million for a state-of-the-art tuna packing facility.[111]

Mike Pence was the third sitting U.S. vice president to visit American Samoa[116] when he made a stopover in Pago Pago in April 2017.[117] He addressed 200 soldiers here during his refueling stop.[118] U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson visited town on June 3, 2017.[119]

In August 2017, the Fono building in Fagatogo was demolished.[120][121]

In 2018, four months of repair took place at the ASG-owned Ronald Reagan Shipyard in Satala.[122]

A North Korean cargo ship seized by the United States arrived in Pago Pago for inspections in 2019.[123]

2009 tsunami

[edit]On September 29, 2009, an earthquake struck in the South Pacific, near Samoa and American Samoa, sending a tsunami into Pago Pago and surrounding areas. The tsunami caused moderate to severe damage to villages, buildings and vehicles and caused 34 deaths and hundreds of injuries.[124][125] It was an 8.3 magnitude earthquake which caused 5-foot (1.5 m) waves to hit the city. It caused major flooding and damaged numerous buildings. A local power plant was disabled, 241 homes were destroyed, and 308 homes had major damage. Shortly after the earthquake, President Barack Obama issued a federal disaster declaration, which authorized funds for individual assistance (IA), such as temporary housing.[126]

The largest wave hit Pago Pago at 6:13 pm local time, with an amplitude of 6.5 feet (2.0 m).[127]

Geography

[edit]

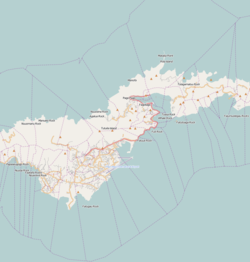

Pago Pago is in the Eastern District of American Samoa, in Ma'oputasi County.[130] It is approximately 2,600 miles (4,200 km) southwest of Hawaii, 1,600 miles (2,600 km) northeast of New Zealand, and 4,500 miles (7,200 km) southwest of California.[131] It is located at 14°16′46″S 170°42′02″W / 14.27944°S 170.70056°W. Pago Pago is located 18 degrees south of the equator.[132]

The city of Pago Pago encompasses several surrounding villages,[133] including Fagatogo, the legislative and judicial capital, and Utulei, the executive capital and home of the Governor.[84] The town is located between steep mountainsides and the harbor. It is surrounded by mountains such as Mount Matafao (2,142 ft), Rainmaker Mountain (1,716 ft), Mount ʻAlava (1,611 ft), Mount Siona (892 ft), Mount Tepatasi (666 ft), and Mount Matai (850 ft), all mountains protecting Pago Pago Harbor.[134] The main downtown area is Fagatogo on the south shore of Pago Pago Harbor, the location of the Fono (territorial legislature), the port, the bus station and the market. The banks are in Utulei and Fagotogo, as are the Sadie Thompson Inn and other hotels. The tuna canneries, which provide employment for a third of the population of Tutuila, are in Atu'u on the north shore of the harbor. The village of Pago Pago is at the western head of the harbor.[135]

Pago Pago Harbor nearly bisects Tutuila Island. It is facing south and situated almost midpoint on the island. Its bay is 0.6 miles (0.97 km) wide and 2.5 miles (4.0 km) long. A 1,630-foot (500 m) high mountain, Mount Pioa (Rainmaker Mountain), is located at the east side of the bay. Half of American Samoa's inhabitants live along Pago Pago's foothills and coastal areas. The downtown area is known as Fagatogo and is home to government offices, port facilities, Samoan High School and the Rainmaker Hotel. Two tuna factories are located in the northern part of town. The town is centered around the mouth of the Vaopito Stream.[20] Pago Pago Harbor collects water from numerous streams, including the 1.7-mile (2.7 km) Vaipito Stream, which is the area's largest watershed. Not far from where Route One crosses Vaipito Stream is Laolao Stream, which discharges into the head of Pago Pago Harbor. It merges with Vaipito Stream in Pago Pago Park, a few yards from the harbor.

In the village of Pago Pago, from Malaloa to Satala, there are a total of eleven rivers or streams. These include Vaipito, Gagamoe, Laolao, Pago, Leau, Vaima, Utumoa, and Aga. Tidal mud flats associated with the mouth of the Vaopito Stream were filled in order to create Pago Pago Park at the head of Pago Pago Harbor.[136]: 24–6 Five species of Gobie fish, Mountain bass, Freshwater eel, Mullet and four shrimp species have been recorded along the lower reach of the Vaipito Stream.[136]: 24–7, 24–13 One of the Goby species, Stiphodon hydoreibatus, is endemic to the Samoan Islands and found nowhere else on Earth.[137]

North of town is the National Park of American Samoa.[138] A climb to the summit of Mount ʻAlava in the National Park of American Samoa provides a bird's-eye view of the harbor and town.[139]

Agriculture

[edit]Agriculture and fishing still provide sustenance for local families.[25]: 8–9

City features

[edit]

The Greater Pago Pago Area stretches into neighboring villages:[28]

- Fagatogo is home to the Pago Pago Post Office, museum, movie theater, bars, and taxi services. It is locally known as Downtown Pago Pago.[5]: 51

- Utulei and Maleimi are home to some Pago Pago-based hotels.

- Satala and Atu'u are home to Pago Pago's tuna industry.

- Tafuna is the location of the Pago Pago International Airport, seven miles (11 km) south of Pago Pago.

Some houses are Western-style; others are more traditional Samoan housing units. All houses have running water and plumbing.[140] It has been described as a "thoroughly Americanized" city.[141] Fagatogo is Pago Pago's chief governmental and commercial center.[142]

Pago Pago Park is a public park by the harbor in Pago Pago. It lies by the Laolao Stream at the very end of Pago Pago Harbor. It is a 20-acre (8.1 ha) recreational complex and culture center. There are a ball field, sports court and boat ramp in the park. The park houses businesses such as the American Samoa Development Bank.[143][144] There are basketball and tennis courts, a football field, a gymnasium, a bowling alley and several Korean food kiosks in the park. The Korean House was built as a social center for the Korean fishermen in town.[17]: 170

National Park

[edit]

Pago Pago is the primary entry point for visits to National Park of American Samoa, and the city is situated immediately south of the park.[3][146] Its park visitor center is located at the head of Pago Pago Harbor: Pago Plaza Visitor Center (Pago Plaza, Suite 114, Pago Pago, AS 96799).[147][148] This center also contains a collection of Samoan artifacts, corals, and seashells.[106]: 479 The center expanded with 700 sq. ft. in July 2019, adding new demonstrations and exhibits. An item at the new exhibit is the skull of a sperm whale which washed up on Ofu Island in 2015. Several video screens and panels inform visitors about Samoan dolphins and whales. The exhibit also contains a 6-foot (1.8 m) by 6-foot (1.8 m) siapo which was made by college students as well as an ʻenu basket woven with traditional materials.[149]

The nearest hotels to the national park are also located in Pago Pago.[150] Other parts of the park, on the islands of Taʻū and Ofu, can be visited via commercial inter-island air carrier from Pago Pago International Airport.

The national park is home to tropical rainforest, tall mountains, beaches, and some of the tallest sea cliffs in the world (3,000 ft; 910 m).[151] It was authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1988 to preserve the paleotropical rain forest, Indo-Pacific coral reefs, and Samoan culture. It officially opened in 1993 when a 50-year lease was signed between the U.S. federal government, the government of American Samoa, and local village chiefs (Matai). It is the only U.S. National Park where the U.S. federal government leases the land from local governments instead of being the land owner. It is a 8,257-acre (3,341 ha) park which provides habitat for a variety of tropical wildlife, including coral reef fish, seabirds, flying fruit bats, and numerous other species of animals. Approximately 2,600 acres (1,100 ha) are on Tutuila, and the remainder is on the other islands and the ocean. The park's offshore coral reefs provide habitat for 1,000 species of coral reef and pelagic fishes.[152] The park is home to over 150 species of coral. Notable terrestrial species are the Pacific tree boa and the Flying Megabat, which has a three-foot (0.91 m) wingspread.[153]

Natural hazards

[edit]Pago Pago is vulnerable to natural and man-made disasters. Vulnerabilities include heavy storms, flooding, tsunamis, mudslides, and earthquakes. American Samoa has experienced several cyclones and tropical storms, which also increase risks of rock slides and floodings.[154]

The capital city is situated at the head of Pago Pago Harbor in a sheltered area that has been described as relatively safe during hurricanes.[141]'

In the past century, Pago Pago has experienced over 50 minor tsunamis. The earliest and most impactful tsunami before the 2009 Samoa earthquake and tsunami occurred in 1917. This event was triggered by a magnitude 8.3 earthquake at the outer border of the northern end of the Tonga Trench, approximately 200 km off the Tutuila coast. The initial wave, reaching a height of about 3 m., resulted in the destruction of numerous houses and two churches. No human casualties were reported. Another notable event was the tsunami associated with the 1960 Valdivia earthquake. While waves in the head of Pago Pago Bay reached a maximum height of 5 m., they caused minimal damage to several houses, with no reported casualties. The most destructive tsunami in Pago Pago's recorded history took place in 2009. Studies indicate that during this incident, wave amplification occurred in the Pago Pago Bay due to its long and narrow morphology. Waves that measured approximately 1 m. at the mouth of Pago Pago Bay surged to a maximum height of 7 m. at the head of Pago Pago Bay. The resulting inundation caused extensive damage in Pago Pago Harbor, extending up to 500 m. inland, and reaching a maximum run-up of 8 m., leading to 34 casualties across Tutuila Island.[155]

Geology

[edit]

Tutuila Island is a basaltic volcanic dome created by five volcanoes aligned along two or possibly three rift zones—fractures in the basement rock. The island's formation dates back to the Pliocene and early Pleistocene epochs, approximately 5 million to 500,000 years ago. Volcanic activity ceased around 10,000 years ago, leaving the island volcanically dormant today. The central feature of Tutuila's geology is the Pago Volcano, which was active between 1.54 and 1.28 million years ago. The volcano's caldera, approximately 6 miles long and 3 miles wide, collapsed 1.27 million years ago, creating Pago Pago Harbor. The natural harbor formed in the partially submerged remnants of the caldera, which cuts deeply into the south-central coast of the island. The village of Pago Pago is situated at the narrowest part of Tutuila, near the center of the collapsed caldera. The northern half of the Pago Volcano shield remains, while the southeastern portion has been eroded to form the harbor.[156][157][158]

Erosion has also played a significant role in shaping the landscape. Following the collapse of the Pago Volcano, the Vaipito Valley and Pago Pago Bay were sculpted by streams and geological processes. The Vaipito Stream, which follows a fault line associated with the volcano, carved steep valley walls, exposing rock formations of basalt, andesite, and trachyte. Over time, colluvial and fluvial sediments filled the lower reaches of the valley, creating a narrow, flat floodplain. Coralline sands and basaltic sediments deposited at the stream's mouth contributed to the formation of a narrow coral-rubble reef flat along Pago Pago Bay's shoreline. Pago Pago Harbor marks the southeastern boundary of the caldera. The northwest rim of the caldera, known as the Maugaloa Ridge, forms the southern boundary of the National Park of American Samoa.[156][157][158]

Climate

[edit]

Pago Pago has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) with hot temperatures and abundant year-round rainfall. All official climate records for American Samoa are kept at Pago Pago. The hottest temperature ever recorded was 99 °F (37 °C) on February 22, 1958. Conversely, the lowest temperature on record was 59 °F (15 °C) on October 10, 1964.[159] The average annual temperature recorded at the weather station at Pago Pago International Airport is 82 °F (28 °C), with a temperature range of about two degrees Fahrenheit separating the average monthly temperatures of the coolest and hottest months.

Pago Pago has been named one of the wettest places on Earth. Due to its warm winters, the plant hardiness zone is 13b. It receives 128.34 inches (3,260 mm) of rain per year. The rainy season lasts from October through May, but the town experiences warm and humid temperatures year-round. Besides it being wetter and more humid from November–April, this is also the hurricane season. The frequency of hurricanes hitting Pago Pago has increased dramatically in recent years. The windy season lasts from May to October. As warmer easterlies are forced up and over Rainmaker Mountain, clouds form and drop moisture on the city. Consequentially, Pago Pago experiences twice the rainfall of nearby Apia in Western Samoa.[8]: 350–351 The average yearly rainfall in Pago Pago Harbor is 197 inches (5,000 mm), whereas in neighboring Western Samoa, it is around 118 inches (3,000 mm) per year.[160]

Rainmaker Mountain, which is also known as Mount Pioa, is a designated National Natural Landmark.[3] It is notable for its ability to extract rain in tremendous quantities. Rising 1,716 feet (523 m) out of the ocean, the Pioa monolith blocks the path of the low clouds heavy with fresh water as they are pushed along by the southeast tradewinds. The southeast ridge of Rainmaker Mountain reaches up into the clouds creating downfalls of enormous proportions.[26]: 30

| Climate data for Pago Pago, American Samoa (Pago Pago International Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1957–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 95 (35) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

91 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 91.0 (32.8) |

91.3 (32.9) |

91.3 (32.9) |

90.7 (32.6) |

89.6 (32.0) |

88.0 (31.1) |

87.7 (30.9) |

88.0 (31.1) |

88.9 (31.6) |

89.6 (32.0) |

90.4 (32.4) |

90.7 (32.6) |

92.4 (33.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 87.8 (31.0) |

88.1 (31.2) |

88.4 (31.3) |

87.8 (31.0) |

86.5 (30.3) |

85.3 (29.6) |

84.6 (29.2) |

84.8 (29.3) |

85.7 (29.8) |

86.4 (30.2) |

87.0 (30.6) |

87.6 (30.9) |

86.7 (30.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 83.0 (28.3) |

83.2 (28.4) |

83.3 (28.5) |

83.0 (28.3) |

82.2 (27.9) |

81.5 (27.5) |

80.9 (27.2) |

80.9 (27.2) |

81.6 (27.6) |

82.1 (27.8) |

82.5 (28.1) |

82.9 (28.3) |

82.3 (27.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 78.2 (25.7) |

78.3 (25.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

77.9 (25.5) |

77.8 (25.4) |

77.2 (25.1) |

77.0 (25.0) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

78.0 (25.6) |

78.2 (25.7) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 75.1 (23.9) |

75.2 (24.0) |

75.0 (23.9) |

74.7 (23.7) |

73.6 (23.1) |

73.4 (23.0) |

72.4 (22.4) |

72.6 (22.6) |

73.3 (22.9) |

73.7 (23.2) |

73.9 (23.3) |

74.7 (23.7) |

70.7 (21.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

68 (20) |

65 (18) |

61 (16) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

59 (15) |

60 (16) |

65 (18) |

59 (15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 15.25 (387) |

13.70 (348) |

10.95 (278) |

11.27 (286) |

11.73 (298) |

6.37 (162) |

7.51 (191) |

6.93 (176) |

7.99 (203) |

10.24 (260) |

12.05 (306) |

14.35 (364) |

128.34 (3,260) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 24.3 | 22.0 | 23.8 | 22.2 | 20.8 | 18.8 | 20.0 | 19.0 | 18.4 | 21.1 | 21.3 | 23.8 | 255.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.8 | 83.3 | 83.2 | 84.0 | 83.6 | 82.0 | 80.4 | 79.8 | 80.2 | 81.5 | 82.3 | 82.1 | 82.1 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 74.8 (23.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

74.3 (23.5) |

73.6 (23.1) |

72.1 (22.3) |

71.6 (22.0) |

72.5 (22.5) |

73.6 (23.1) |

74.1 (23.4) |

74.5 (23.6) |

73.8 (23.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 165.3 | 150.3 | 179.2 | 132.2 | 123.3 | 113.7 | 148.0 | 168.0 | 196.0 | 159.6 | 156.7 | 156.8 | 1,849.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 43 | 48 | 37 | 35 | 34 | 42 | 47 | 54 | 41 | 41 | 39 | 42 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[161][162][163] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 508 | — | |

| 1930 | 708 | 39.4% | |

| 1940 | 934 | 31.9% | |

| 1950 | 1,586 | 69.8% | |

| 1960 | 1,251 | −21.1% | |

| 1970 | 2,451 | 95.9% | |

| 1980 | 2,491 | 1.6% | |

| 1990 | 3,518 | 41.2% | |

| 2000 | 4,278 | 21.6% | |

| 2010 | 3,656 | −14.5% | |

| 2020 | 3,000 | −17.9% |

The village of Pago Pago proper had a 2010 population of 3,656. However, Pago Pago also encompasses neighboring villages. The Greater Pago Pago Area was home to 11,500 residents in 2011.[164] Around 90 percent of American Samoa's population lives around Pago Pago.[165][166] American Samoa's population grew by 22 percent in the 1990s; nearly all of this growth took place in Pago Pago.[167]

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, 74.5% of Pago Pago's population are of "Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Island" race. 16.6% were Asian, while 4.9% were white.[168] In Pago Pago proper, residential communities are mostly found in the Vaipito Valley.[136]: 24–23

The proportion of Pago Pago residents born outside of American Samoa was 26 percent in the early 1980s, and 39 percent in the late 1980s. The percentage of residents born abroad reached 44 percent in 1990. Many of the residents are American Samoans who were born abroad, and the village also has had an increasing number of new residents from Far East countries such as South Korea.[136]: 24–22

The village of Pago Pago, the Greater Pago Pago Area and Maʻopūtasi County observed a notable reduction in population during the period from 2010 to 2020. Specifically, the county registered a 16.8 percent decline in population, while Pago Pago proper recorded an 18 percent decrease. This decline surpassed the overall population decrease for American Samoa, which stood at 10.5 percent during the same timeframe. Among the villages in the county, only Anua experienced a positive growth in population, contrasting with declines in villages such as Fagatogo (-16.8%), Satala (-26.6%), and Utulei (-30%).[169]

Government

[edit]

Pago Pago is the seat of the judiciary (Fagatogo), legislature and Governor's Office (Utulei).[28]

Pago Pago operates under a dual local government system, consisting of county councils and village councils. Each system serves distinct yet complementary roles in governance and community administration. Pago Pago is part of Maʻopūtasi County, which is governed by a county council responsible for regional services such as law enforcement, public health initiatives, and broader infrastructure projects. The county council is composed of elected officials who serve four-year terms, ensuring governance that aligns with the needs of the area. On a more localized level, the Pago Pago Village Council (PPVC) oversees the daily management of the village. This council, made up of elected village leaders, handles essential community functions, including maintaining local infrastructure, managing budgets, and ensuring the safety and welfare of residents. In addition to administrative duties, the council plays a vital role in resolving disputes and preserving traditional Samoan customs and values.[170]

Education

[edit]The Feleti Barstow Public Library is located in Pago Pago.[171] In 1991, severe tropical Cyclone Val hit Pago Pago, destroying the library that existed there. The current Barstow library, constructed in 1998, opened on April 17, 2000.[172]

The American Samoa Community College (ASCC) was founded in July 1970 by the American Samoa Department of Education. The college's first courses were taught in 1971 at the Lands and Survey Building in Fagatogo. At the time, the college had a total enrollment of 131 students. In 1972, the college moved to the former Fialloa High School in Utulei, before ultimately moving to its current location in Mapusaga in 1974.[173]

Culture

[edit]Religion

[edit]Pago Pago is home to a variety of Christian denominations, including the New Apostolic Church, the Congregational Christian Church of Jesus Christ (CCCJS), the Pago Pago Assembly of God, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), the Susana Uesele Methodist Church, and the First Chinese Baptist Church of American Samoa. The All People’s Pentecostal Church was dedicated in August 2017, and a new Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Hall opened in 2016. The town also has a Baháʼí Center. In neighboring Satala, there is a Seventh-day Adventist Church, while Fagatogo is the site of the Roman Catholic Co-Cathedral of St. Joseph the Worker.[174]

Several congregations in Pago Pago, including Assemblies of God, the Congregational Christian Church of American Samoa (CCCAS), and Methodist churches, participate in joint worship services through the World Council of Churches. However, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and certain other denominations do not take part in these shared services.[175]

Economy

[edit]

Pago Pago is the center of commerce in American Samoa.[173][176][177] It is home to all the industry and most of the commerce in American Samoa.[17]: 166 It is the number one port in the United States in terms of value of fish landed - about $200,000,000 per year.[9] In 2007, tuna exports accounted for 93% of all exports, amounting to $446 million.[178]

Tuna canning is the main economic activity in town. Exports are almost exclusively tuna canneries such as Chicken of the Sea and StarKist, which are both located in Pago Pago. These also occupy 14 percent of American Samoa's total workforce as of 2014.[179] The most industrialized area in the territory can be found between Pago Pago Harbor and the Tafuna-Leone Plain, which also are the two most densely populated places in the islands.[180]

American Samoa was the world's fourth-largest tuna processor in 1993. The primary industry is tuna processing by the Samoa Packing Co. (Chicken of the Sea) and StarKist Samoa, a subsidiary of H.J. Heinz. The first cannery was opened in 1954. Canned fish, canned pet food, and fish meal from skin and bones account for 93 percent of American Samoa's industrial output.[8]: 353

Dining establishments, amusement facilities, professional services, and bars can be found throughout Pago Pago. Pago Pago proper was home to 225 registered commercial enterprises as of year 2000. Within the Pago Pago watershed, farmland (faatoaga) are located in two areas in the southern half of the Vaipito Valley as well as in Happy Valley and on the west side of Pago Pago village. Farmland is also found by Fagatogo, Atu'u, Punaoa Valley, Lepua, Aua, and Leloaloa.[136]: 24–24, 24–25

Centers for shopping are Pago Plaza, which consists of smaller stores selling handcrafts and souvenirs, and Fagatogo Square Shopping Center, which is home to larger shops.[133] This shopping mall is next-door to Fagatogo Market in Fagatogo, which is considered the main center of Pago Pago. It is home to several restaurants, shops, bars, and often live entertainment and music. Souvenirs are often sold at the market when cruise ships are visiting town. Locals also sell handmade crafts at the dock and on main street. Mount ʻAlava, the canneries in Atu'u, Rainmaker Mountain (Mount Pioa), and Pago Pago Harbor are all visible from the market. The main bus station is located immediately behind the market.[181][182]

Pago Pago is a duty-free port and prices on imported goods are lower than in other parts of the South Pacific Ocean.[17]: 166 Governor H. Rex Lee signed a law making Pago Pago a duty-free port in May 1967.[25]: 285

It is a wealthier city than nearby Apia, capital of Samoa.[183][184][185]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism in American Samoa is centered around Pago Pago. It receives 34,000 visitors per year, which is one-fourth of neighboring country of Samoa. 69.3 percent of visitors are from the United States as of 2014.[186]

Until 1980, one could experience the view of Mt. Avala by taking an aerial tramway over the harbor, but on April 17 of that year a U.S. Navy plane, flying overhead as part of the Flag Day celebrations, struck the cable; the plane crashed into a wing of the Rainmaker Hotel.[187] The tramway was repaired, but closed not long after. The tram remains unusable, although according to Lonely Planet, plans have been put forth to reopen it, but in January 2011 the cable was damaged by Tropical Cyclone Wilma, fell into the harbor and has not been repaired. Governor Lolo Matalasi Moliga announced in 2014 that he would look into restoring the cable car.[188]

The Sadie Thompson Inn, on the outskirts of Pago Pago, is a hotel and restaurant that is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

The Greater Pago Pago Area is home to more than 10 hotels:[106]: 483–485

Transportation

[edit]

Pago Pago Harbor is the port of entry for vessels arriving in American Samoa.[192] Many cruise boats and ships land at Pago Pago Harbor for reprovision reasons, such as to restock on goods and to utilize American-trained medical personnel.[193] Pago Pago Harbor is one of the world's largest natural harbors.[164] It has been named one of the best deepwater harbors in the South Pacific Ocean,[4][194] or one of the best in the world as a whole.[195]

Pago Pago is a port of call for South Pacific cruise ships, including Norwegian Cruise Line[196] and Princess Cruises.[197] However, cruise ships do not take on passengers in Pago Pago, but typically arrive in the morning and depart in the afternoon. Thirteen cruise ships were scheduled to visit Pago Pago in 2017, bringing 31,000 visitors.[198] Pago Pago Harbor can accommodate two cruise ships at the same time, and has done so on several occasions.[199]

Pago Pago International Airport (PPG) is located at Tafuna, eight miles (13 km) southwest of Pago Pago. There are international flights to Samoa 4–7 times daily by Polynesian Airlines:[132] Pago Pago is a 35-minute flight from Apia in Samoa. Most flights are to and from Fagali'i.[106]: 512 [200] There is only one flight destination from the territory to the United States: Honolulu International Airport, a five-hour flight from Pago Pago by Hawaiian Airlines. Of the 88,650 international arrivals in 2001, only 10 percent were tourists. The rest came to visit relatives, for employment reasons, or in transit. Most international visitors are from the independent country of Samoa.[106]: 468–469

Scheduled intra-territorial flights are available to the islands of Taʻū and Ofu, which take 30 minutes by air from Pago Pago.

A ferry called MV Lady Naomi runs between Pago Pago and Apia, Samoa, once a week.[201]

Bus and taxi services are based in Fagatogo.[202]

Historical sites

[edit]

Sixteen remaining structures from the U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Historic District are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. These include the Government House, Courthouse of American Samoa, Jean P. Haydon Museum, Navy Building 38, and other buildings.

World War II fortifications

[edit]Near Pila F. Palu Co. Inc. Store, a road runs up the hill into Happy Valley, and on the side of this road, six World War II ammunition bunkers can be seen on the left before reaching a dirt road. The dirt road, also located on the left side, leads to a big concrete bunker which was used as naval communications headquarters during World War II.[203]: 411–412 Over fifty pillbox fortifications can be found along the coastline on Tutuila Island. The largest of these is the Marine Corps communication bunker in Pago Pago.[204] It is located in the Autapini area, which is between Malaloa and Happy Valley.[203]: 416–417

During World War II, guns were emplaced at Blunt's and Breaker's Points, covering Pago Pago Harbor.[76]: 85–86

Flora

[edit]At one time there were a number of mangrove forests around the Pago Pago area, but these are now all gone, with the exception of a few scattered individual trees surviving at Aiia on the east side of Pago Pago Bay. No trace of mangroves are longer found within Fagatogo village limits, thus contradicting its name (“bay of mangroves).[205]

Fauna

[edit]Black turtles and Hawksbill turtles have been recorded in Pago Pago Harbor. The area also attracts seabirds like the Crested tern and the Blue-gray noddy, which are known to roost and nest nearby. The Cardinal honey-eater frequents the ridges above Pago Pago, feeding on nectar from native plants. Additionally, the Wandering tattler has been spotted along a mountain stream just west of the town. The Black rat has also been recorded in Pago Pago.[206]

The Red-vented bulbul, an introduced bird species, has become widespread on Tutuila Island. It was first observed in Apia during the 1940s and later reported in Pago Pago in 1958. Another introduced species, the Rock dove, has a more recent and less well-documented history in the Samoan Islands. Records from the 1950s indicate that a flock of 20 Rock Doves was kept by a family in Pago Pago during this period.[207]

The Grey-backed tern is occasionally observed feeding within Pago Pago Harbor, while the Black noddy is frequently sighted flying over the same area. The Common myna, an adaptable urban bird, is commonly encountered in the developed regions surrounding Pago Pago.[208]

Landmarks

[edit]

Landmarks include:[5]: 54 [17]: 167–169

- National Park of American Samoa, immediately north of town

- NPS Visitor Center, exhibit and shop

- U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Historic District, sixteen buildings are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Government House is a colonial mansion atop Mauga o Ali'i (the chief's hill), which was erected in 1903

- The Fono is the territorial legislature

- The Courthouse is a two-story colonial-style house listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Jean P. Haydon Museum was constructed in 1917 and houses historical artifacts such as canoes. It is named for its founder, the wife of Governor John Morse Haydon

- Blunts Point Battery, erected as a part of the fortification following the attack on Pearl Harbor[209]

- Breakers Point Naval Guns, World War II-era defensive fortification

- Rainmaker Mountain (Pioa Mountain), designated National Natural Landmark[3]

- Utulei Beach, beach in Utulei

- Navy Building 38, historic radio station in Fagatogo

- Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center, visitor center for National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

- Air Disaster Memorial, in Utulei. Monument for the eight deceased during a 1980 airplane crash

In popular culture

[edit]

- Rain (1921) by W. Somerset Maugham is set in Pago Pago.[106]: 463 [211] Movie adaptions include Sadie Thompson (1928), Rain (1932), and Miss Sadie Thompson (1953).

- The Blonde Captive (1931) was filmed in Pago Pago.[212]

- The Hurricane (1937) and its sequel, Hurricane (1979), were set in Pago Pago. The 1937 film was filmed in Pago Pago.[212]

- The storyline in the film South of Pago Pago (1940) is set here. This movie was partly shot in Pago Pago, although most filming took place in Hawai'i and Long Beach, CA.[213]

- A jungle village resembling Pago Pago was created for motion picture in Two Harbors, Catalina Island, CA.[214] Several Sadie Thompson films were shot here.

- Lost and Found on a South Sea Island (1923) is set in Pago Pago.

- Next Goal Wins (2014), British documentary filmed in Pago Pago.

- Samoa, California was named in honor of American Samoa. It was assumed that the harbor in Pago Pago looked similar to that of the town, and it consequentially got the name Samoa, CA in the 1890s.[215]

- In the Sweet Pie and Pie (1941), The Three Stooges short. Pago Pago is mentioned as being one of the locations for the fictional Heedam Neckties stores.

- In Better Call Saul (2015), Saul Goodman graduated from the fictional American Samoa Law School.

Notable people

[edit]

- Peter Tali Coleman, 43rd, 51st, and 53rd Governor of American Samoa

- Al Harrington, actor most known for his role in Hawaii Five-O[216]

- Gary Scott Thompson, director and television producer[217]

- John Kneubuhl, screenwriter

- Lealaifuaneva Peter Eugene Reid, businessman and Fautasi Racing Champion.[218]

- Mary Jewett Pritchard, Siapo artist.[219]

- Shalom Luani, NFL player for the Los Angeles Chargers

- Mauga Moi Moi, paramount Aliʻi, signatory of the Deed of Cession, and initiator of the Mau movement.

- Junior Siavii, Former NFL player for the Kansas City Chiefs, Dallas Cowboys, and the Seattle Seahawks

- Jonathan Fanene, Former NFL player for the Cincinnati Bengals

- Mosi Tatupu, Former NFL player for the New England Patriots, and the Los Angeles Rams

- Shaun Nua, Former NFL player for the Pittsburgh Steelers

- Isaac Sopoaga, Former NFL player for the San Francisco 49ers, Philadelphia Eagles, New England Patriots, and the Arizona Cardinals

- Daniel Teʻo-Nesheim, Former NFL player for the Philadelphia Eagles, and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Frank Solomon, rugby player

- Faauuga Muagututia, US Navy Seal and Winter Olympic competitor

- Violeta Shafer Tavai Lea’e Dilauro, Samoan American Cultural Liaison in Philadelphia and advocate for Samoan athletes.[220]

- Amata Coleman Radewagen, Delegate in the U.S. House of Representatives

- Fofó Iosefa Fiti Sunia, first non-voting Delegate from American Samoa to the U.S. House of Representatives

- Palauni Ma Sun, American football offensive lineman

- Monica Galetti, UK-based chef and restauranteur

- Joey Iosefa, football player

- Mabel Reid, first woman elected to the American Samoa House of Representatives.[221]

- Bob Apisa, football player

- Domata Peko, football player

- Isaako Aaitui, football player

- Kennedy Polamalu, football coach and former player

- Gabe Reid, former football tight end for the NFL's Chicago Bears

- Nicky Salapu, soccer player

- Trevor Misipeka, football player

- Cocoa Samoa, wrestler

- Mighty Mo, kickboxer

- Mageo Felise, member of the American Samoa House of Representatives and Senate. Founded several Catholic schools in the territory.[222]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Ann G. and Esther Tuttle (2004). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt. Page 604. ISBN 9780787299705.

- ^ a b United States Central Intelligence Agency (2016). The World Factbook 2016–17. Government Printing Office. Page 19. ISBN 9780160933271.

- ^ a b c Grabowski, John F. (1992). U.S. Territories and Possessions (State Report Series). Chelsea House Pub. ISBN 9780791010532.

- ^ a b Kristen, Katherine (1999). Pacific Islands (Portrait of America). San Val. ISBN 9780613032421.

- ^ a b Leonard, Barry (2009). Minimum Wage in American Samoa 2007: Economic Report. Diane Publishing. ISBN 9781437914252.

- ^ a b c Stanley, David (1993). South Pacific Handbook. David Stanley. ISBN 9780918373991.

- ^ a b "NATURAL HISTORY GUIDE TO AMERICAN SAMOA" (PDF). National Park Service. 2009. p. 48. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Hamel, Jean-Francois (2018). World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation. Volume II: The Indian Ocean to the Pacific. Academic Press. Page 636. ISBN 9780128052037.

- ^ Chi, Sang and Emily Moberg Robinson (2012). Voices of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience. ABC-CLIO. Page 54. ISBN 9781598843552.

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office (2010). Impact of Increased Minimum Wage of [i.e. On] American Samoa and CNMI. Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Page 13. ISBN 9780160813726.

- ^ United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Pacific Ocean Division (1975). Water Resources Development by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in American Samoa, 1975. Division Engineer, U.S. Army Engineer Division, Pacific Ocean, Corps of Engineers. Page 36.

- ^ Carter, John (1984). Pacific Islands Yearbook 1981. Pacific Publications Pty, Limited. Page 49. ISBN 9780858070493.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Volume 25. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. Page 288. ISBN 9780852299616.

- ^ C. Balme (2006). Pacific Performances: Theatrically and Cross-Cultural Encounter in the South Seas. Springer. Page 156. ISBN 9780230599536.

- ^ a b c d e f Swaney, Deanna (1994). Samoa: Western & American Samoa: a Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 9780864422255.

- ^ "Raiders draft Shalom Luani". 30 April 2017.

- ^ Mack, Doug (2017). The Not-Quite States of America: Dispatches From the Territories and Other Far-Flung Outposts of the USA. W.W. Norton & Company. Page 62. ISBN 9780393247602.

- ^ a b Lal, Brij V. and Kate Fortune (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press. Page 101. ISBN 9780824822651.

- ^ Sparks, Karen Jacobs (2010). Britannica Book of the Year 2010. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. Page 509. ISBN 9781615353668.

- ^ Atkinson, Brett and Charles Rawlings-Way (2016). Lonely Planet Rarotonga, Samoa & Tonga (Travel Guide). Lonely Planet. Page 147. ISBN 9781786572172.

- ^ a b "Rainmaker Mountain in Tutuila". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ "American Samoa Is The Empty Slice Of Bliss You've Been Craving". huffingtonpost.com. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Sunia, Fofo I.F. (2009). A History of American Samoa. Amerika Samoa Humanities Council. ISBN 9781573062992.

- ^ a b c d Shaffer, Robert J. (2000). American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag. Island Heritage. ISBN 9780896103399.

- ^ a b The city trip guide for Pago Pago (2024). YouGuide Ltd. Page 2. ISBN 9781837062799.

- ^ a b c Cruise Travel Vol. 2, No. 1 (July 1980). Lakeside Publishing Co. Page 60. ISSN 0199-5111.

- ^ "Uber, schmuber. Behold the buses of Pago Pago ..." LA Times. 10 November 2015. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ "Language in Samoa | Frommer's". Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ Craig, Robert D. (2004). Handbook of Polynesian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. Page 17. ISBN 9781576078945.

- ^ Fraser, Peter (2010). More Curious Than Cautious. Dog Ear Publishing. Page 122. ISBN 9781598587708.

- ^ Leib, Amos Patten (1972). The Many Islands of Polynesia. Schuster Merchandise. Page 60. ISBN 9780684130101.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: a history of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 123.

- ^ a b c Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1980). Amerika Samoa. Arno Press. ISBN 9780405130380.

- ^ Richards, Rhys (1992). Samoa's Forgotten Whaling Heritage: American Whaling in Samoan Waters 1824-1878. Lithographic Services, Limited. Page 63. ISBN 9780473016074.

- ^ Stahl, Dean A. and Karen Landen (2001). Abbreviations Dictionary. CRC Press. Page 1451. ISBN 9781420036640.

- ^ Sand, Christophe and David J. Addison (2008). Recent Advances in the Archaeology of the Fiji/West-Polynesia Region. Department of Anthropology, Gender and Sociology. University of Otago. Dunedin: New Zealand. Page 93. ISBN 9780473145866.

- ^ Craig, Peter (2009). Natural history guide to American Samoa. National Park of American Samoa. Page 19. Retrieved on January 20, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/npsa/learn/education/upload/NatHistGuideAS09.pdf.

- ^ Sand, Christophe and David J. Addison (2008). Recent Advances in the Archaeology of the Fiji/West-Polynesia Region. Department of Anthropology, Gender and Sociology. University of Otago. Dunedin: New Zealand. Page 110. ISBN 9780473145866.

- ^ Rieth, Tim (2008). How Dark Are They? The Samoan Dark Ages, ~1500-1000 BP. Retrieved on January 20, 2024, from https://www.academia.edu/1758604/How_Dark_Are_They_The_Samoan_Dark_Ages_1500-1000_BP.

- ^ Sand, Christophe and David J. Addison (2008). Recent Advances in the Archaeology of the Fiji/West-Polynesia Region. Department of Anthropology, Gender and Sociology. University of Otago. Dunedin: New Zealand. Page 91. ISBN 9780473145866.

- ^ Sand, Christophe and David J. Addison (2008). Recent Advances in the Archaeology of the Fiji/West-Polynesia Region. Department of Anthropology, Gender and Sociology. University of Otago. Dunedin: New Zealand. Page 103. ISBN 9780473145866.

- ^ Pearl, F. B. (2004). The Chronology of Mountain Settlements on Tutuila, American Samoa. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 113(4), 331–348. Page 334. Retrieved on January 21, 2024, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20707242.

- ^ "TS Tongan War in Tutuila : Samoan Mythology".

- ^ Todd, Ian (1974). Island Realm: A Pacific Panorama. Angus & Robertson. Page 69. ISBN 9780207127618.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (1994). The Samoa Islands: Constitution, pedigrees and traditions. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Page 436. ISBN 9780824816339.

- ^ Linnekin, Jocelyn, Hunt, Terry, Lang, Lang and McCormick, Timothy (November 2006). "Ethnographic Assessment and Overview: National Park of American Samoa". Technical Report 152. Pacific Cooperative Parks Study Unit. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

- ^ Lutali, A.P. and William J. Stewart. The Chieftal System in Twentieth Century America: Legal Aspects of the Matai System in the Territory of American Samoa. 4 Ga. J. Int’l & Compar. L. 387 (1974). Page 390. Retrieved on January 20, 2024, from https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/gjicl/vol4/iss2/8/.

- ^ U.S. National Park Service (1988). “National Park Feasibility Study: American Samoa”. Page 29. Retrieved on December 23, 2024, from https://npshistory.com/publications/npsa/feasibility-study.pdf

- ^ Salmond, Anne (2011). Bligh: William Bligh in the South Seas. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9781742287812.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Page 68. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Knox, Thomas W. (1889). The Boy Travellers Australasia. Page 140.

- ^ Neems, Hugh (2014). Beyond The Reef. Page 19. ISBN 9781291739145.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 38. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Neems, Hugh (2016). A Vision Shared. George Lambert. Page 45. ISBN 9780955728235.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Pages 2, 144 and 183. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Pages 147 and 149. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Pages 40-41. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Sorensen, Stan and Theroux, Joseph. The Samoan Historical Calendar, 1606-1997. Government of American Samoa. Page 113.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 41. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Aitaoto, Fuimaono Fini (2021). Progress and Developments of the Churches in the Samoan Islands: Early 21St Century. LifeRich Publishing. Page 96. ISBN 9781489735867.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Page 112. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Pages 41-42. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 43. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 183. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ Freeman, Donald B. (2010). The Pacific. Routledge. Page 167. ISBN 9780415775724.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Page 125. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Gilson, Richard Phillip (1970). Samoa 1830 to 1900: The Politics of a Multi-cultural Community. Oxford University Press. Page 279. ISBN 9780195503012.

- ^ Levi, Werner (1947). American-Australian Relations. University of Minnesota Press. Page 73. ISBN 9780816658152.

- ^ Dixon, Joe C. (1980). The American Military and the Far East. Diane Publishing. Page 139. ISBN 9781428993679.

- ^ Stanley, George Edwards (2005). The Era of Reconstruction and Expansion (1865–1900). Gareth Stevens. Page 36. ISBN 9780836858273.

- ^ Pafford, John (2013). The Forgotten Conservative: Rediscovering Grover Cleveland. Regnery Publishing. Page 61. ISBN 9781621570554.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 65. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Pearl, Frederic and Sandy Loiseau-Vonruff (2007). “Father Julien Vidal and the Social Transformation of a Small Polynesian Village (1787–1930): Historical Archaeology at Massacre Bay, American Samoa”. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 11(1): pages 37-39. ISSN 1092-7697.

- ^ a b c Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-military Study. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313313950.

- ^ Churchward, William Brown (1887). My Consulate in Samoa: A Record of Four Years' Sojourn in the Navigators Islands, with Personal Experiences of King Malietoa Laupepa, His Country and His Men. Richard Bentley and Son. Pages 335-346.

- ^ Ryan, James and Joan Schwartz (2021). Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000548785.

- ^ Edwards, Elizabeth (2021). Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000181296.

- ^ Chappell, David A. (2016). Double Ghosts: Oceanian Voyagers on Euroamerican Ships. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781315479118.

- ^ Cook, Kealani (2016). Return to Kahiki: Native Hawaiians in Oceania. Cambridge University Press. Page 95. ISBN 9781107195899.

- ^ "Robert Louis Stevenson". Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 February 2019.

- ^ Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Family and Church History Department (2005). Deseret News 2006 Church Almanac: Joseph’s Journeys. Deseret Book Company. Page 285. ISBN 9781590385562.