Leopold Bloom

| Leopold Bloom | |

|---|---|

| Ulysses character | |

Drawing of Leopold Bloom by Joyce | |

| Created by | James Joyce |

| Based on | Odysseus Italo Svevo Alfred Hunter Leopoldo Popper |

| Portrayed by | Zero Mostel David Suchet Milo O'Shea Stephen Rea |

| Voiced by | Ronnie Walsh Henry Goodman |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Henry Flower |

| Nickname | Poldy |

| Occupation | Advertising agent |

| Family | Rudolph Bloom (né Rudolf Virág) (father) Ellen Bloom (née Higgins) (mother) |

| Spouse | Marion (Molly) Tweedy (m. 1888) |

| Children | Millicent (Milly) Bloom (b. 1889) Rudolph (Rudy) Bloom (b. 1893 – d. 1893) |

| Relatives | Lipoti Virag (grandfather) |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Nationality | Irish |

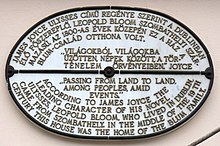

Leopold Bloom is the fictional protagonist and hero of James Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses. His peregrinations and encounters in Dublin on 16 June 1904 mirror, on a more mundane and intimate scale, those of Ulysses/Odysseus in Homer's epic poem: The Odyssey.

Factual antecedents

[edit]Joyce first started planning a piece in 1906 that he described as "deal[ing] with Mr. Hunter" to be included as the final story in Dubliners, which he later retitled "Ulysses" in a letter to his brother that year.[1] The protagonist of the piece was apparently to be based on a Dubliner named Alfred H. Hunter, who, according to Joyce's biographer, Richard Ellmann, was rumored around town to have been from a Jewish background and to have an unfaithful, promiscuous wife.[2] The same source that related this reputation to Ellmann also suggested that on the night of 20 June 1904, an intoxicated Joyce approached a young woman standing alone in St. Stephen's Green and spoke to her just before her escort appeared and, feeling Joyce has insulted his date, proceeded to thrash the future author. Sometime after this, according to the Ellmann's source, Hunter appeared on the scene, helped Joyce to his feet, and walked him home. The incident, if accurate, runs parallel to Bloom's rescue of Stephen Dedalus in the closing scene of the Circe episode of Ulysses.

Another Dublin-based model for Bloom, and especially as regards the character's nationalist politics, was the successful entrepreneur and municipal politician Albert L. Altman. Altman owned and operated one of the largest salt depots and distributors in the city during Joyce's entire youth in Ireland and, as noted continuously throughout the period in the Dublin press, was involved in nationalist controversies and Home Rule politics where he was well acquainted with John Joyce, Joyce's father. He was elected to the Dublin Corporation City Council as Usher's Quay Town Councilor from 1901 to 1903 and died in office that final year. Like Bloom, Altman had a son who died in infancy and a father who died by his own hand through accidental poisoning.[3]

Another model for Bloom was undoubtedly Italo Svevo.[4][5][6] Svevo was the nom de plume of Hector (Ettore) Schmitz, who was one of Joyce's favorite students when he was a Berlitz English language tutor in Trieste. Schmitz was born and raised a Jew but converted to Catholicism to marry. Joyce had many conversations with him about literature, art, his Jewish background, and Judaism. After Joyce allowed him to read both Dubliners and a draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Schmitz revealed to his tutor that he too was a novelist, although his first published novels had gone unnoticed by the reading public. After Joyce was given these novels and read them, he declared Schmitz to be an overlooked important Italian writer and worked during the course of the rest of their friendship to get his former pupil's works noticed and published. It has been argued as well that the protagonists of Svevo's novels may have influenced Bloom's personality and habits as a Jewish character.[7]

The character's name (and maybe some of his personality) may have been inspired by Joyce's Trieste acquaintance Leopoldo Popper. Popper was a Jew of Bohemian descent who had hired Joyce as an English tutor for his daughter Amalia. Popper managed the company of Popper and Blum and it is possible that the name Leopold Bloom was invented by taking Popper's first name and anglicizing the name Blum.[8][9]

Fictional biography

[edit]Bloom is introduced to the reader as a man of appetites:

Mr. Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liverslices fried with crustcrumbs, fried hencods' roes. But most of all, he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.

The Bloom character, born in 1866, is the only son of Rudolf Virág (a Hungarian Jew from Szombathely who emigrated to Ireland, converted from Judaism to Protestantism, changed his name to Rudolph Bloom[10] and later died by suicide), and of Ellen Higgins, an Irish Catholic.[11] He is uncircumcised.[12] They lived in Clanbrassil Street, Portobello. Bloom converted to Catholicism to marry Marion (Molly) Tweedy on 8 October 1888. The couple has one daughter, Millicent (Milly), born in 1889; their son Rudolph (Rudy), born in December 1893, died after 11 days. The family lives at 7 Eccles Street in Dublin.

Episodes (chapters) in Ulysses relate a series of encounters and incidents in Bloom's contemporary odyssey through Dublin in the course of the single day of 16 June 1904 (although episodes 1 to 3, 9 and to a lesser extent 7, are primarily concerned with Stephen Dedalus, who in the plan of the story is the counterpart of Telemachus). Joyce aficionados celebrate 16 June as 'Bloomsday'.

As the day unfolds, Bloom's thoughts turn to the affair between Molly and her manager, Hugh 'Blazes' Boylan (obliquely, through, for instance, telltale ear worms), and, prompted by the funeral of his friend Paddy Dignam, the death of his child, Rudy. The absence of a son may be what leads him to take a shine to Stephen, for whom he goes out of his way in the book's latter episodes, rescuing him from a brothel, walking him back to his own house, and even offering him a place there to study and work. The reader becomes familiar with Bloom's tolerant, humanistic outlook, his penchant for voyeurism and his (purely epistolary) infidelity. Bloom detests violence, and his relative indifference to Irish nationalism leads to disputes with some of his peers (most notably 'the Citizen' in the Cyclops chapter). Although Bloom has never been a practising Jew, converted to Roman Catholicism to marry Molly, and has in fact received Christian baptism on three occasions, he is of partial Jewish descent and is sometimes ridiculed and threatened because of his being perceived as a Jew.[13]

Richard Ellmann, Joyce's biographer, described Bloom as "a nobody", who "has virtually no effect upon the life around him". In this Ellmann found nobility: "The divine part of Bloom is simply his humanity - his assumption of a bond between himself and other created beings."[14] Hugh Kenner took issue with the view of Bloom as "the little man", citing textual evidence to show that he is taller than average. He also has "relative wealth, an exalted dwelling-place, handsome features, a polysemous wit, a famously beautiful wife". Kenner admitted that the evidence came late in the text. He argued that Joyce gave the initial impression of Bloom's ordinariness because of the parallel with Ulysses, whose "normal strategy was to withhold his identity".[15] Others such as Joseph Campbell see him more as an Everyman figure, a world (cosmopolis) traveler who, like Homer's Odysseus "visited the dwellings of many people and considered their ways of thinking" (Odyssey 1.3).

One critic has argued that Joyce used the doctrines of the Incarnation cited early in Ulysses to characterize his relation to both Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom and their relation to each other. The theme of "reincarnation," also introduced early in the novel, has been linked to one of the doctrines to signify that Bloom is the mature Joyce in another form and that Joyce speaks through him.[16]

Popular culture

[edit]

Joyce told Sylvia Beach that Holbrook Jackson resembled Bloom.[17]

Writer-director Mel Brooks used the name "Leo Bloom" for the mousy accountant protagonist in his film/musical The Producers.[18] Leo is a nervous accountant, prone to panic attacks, who keeps a security blanket to calm himself. Nevertheless, it is Leo who has the idea of how to make money from a failed play. In the 2001 stage musical and its 2005 film adaptation, after realizing his inner potential, Leo loudly asks "When's it gonna be Bloom's Day?" Hidden in the background of the office of Max Bialystock is a calendar marked for 16 June, which is Bloomsday.[19]

Former Pink Floyd bandmate Roger Waters references Leopold Bloom in his song "Flickering Flame" as sitting with Molly Malone.[20]

Jeffrey Meyers suggested in "Orwell's Apocalypse: Coming Up for Air, Modern Fiction Studies" that George Orwell's character George Bowling was modelled on Leopold Bloom.[21]

Grace Slick's song "Rejoyce", from the album After Bathing at Baxter's, concerns the novel Ulysses; Bloom is mentioned in the song.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ Ellmann, Richard (1975). Selected Letters of James Joyce. Viking Press. pp. 112, 128. ISBN 0-670-63190-6.

- ^ Ellmann, Richard (1982). James Joyce. Oxford University Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 0-19-503381-7.

- ^ Davison, Neil (2022). An Irish-Jewish Politician, Joyce's Dublin, and Ulysses: The Life and Times of Albert L. Altman. University Press of Florida: James Joyce Series. ISBN 9780813069555.

- ^ "James Joyce, Italo Svevo & Leopold Bloom". iseultandbloom.org.

- ^ "James Joyce and Italo Svevo: the story of a friendship". The Irish Times.

- ^ Staley, Thomas F. (1964). "The Search for Leopold Bloom: James Joyce and Italo Svevo". James Joyce Quarterly. 1 (4): 59–63. JSTOR 25486462.

- ^ Davison, Neil (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography, and "the Jew" in Modernist Europe. Cambridge University Press (published 1996). pp. 155–184. ISBN 0-521-55181-1.

- ^ Hughes, Eileen Lanouette (2 February 1968), The mystery lady of Giacomo Joyce. A newly published work reveals an early Molly Bloom Life Magazine.

- ^ Partridge, Craig (2016), Juda Loebl Popper of Ostrovec-Lhotka, Bohemia, and His Family, privately printed, pp. 241ff.

- ^ Note: virág means "flower" in Hungarian, hence the new surname, "Bloom"

- ^ Steinberg, Erwin R. (1986). "The Religion of Ellen Higgins Bloom". James Joyce Quarterly. 23 (3): 350–355. JSTOR 25476739.

- ^ Joyce, James (2 February 1922). "Annotations to James Joyce's Ulysses/Nausicaa/356". en.wikibooks.org.

Well the foreskin is not back.

- ^ Hezser, Catherine (18 May 2005). ""Are You Protestant Jews or Roman Catholic Jews?": Literary Representations of Being Jewish in Ireland". Modern Judaism. 25 (2): 159–188. doi:10.1093/mj/kji011 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (14 May 1987). Richard Ellmann dies at 69; Eminent James Joyce Scholar. The New York Times.

- ^ Kenner, Hugh (1987). "Ulysses". The Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 43–45. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Lang, Frederick K. (1993). "Ulysses" and the Irish God. Lewisburg, London and Toronto: Bucknell University Press, Associated University Presses. pp. 20–2, 67–91. ISBN 0838751504.

- ^ Rintoul, M. C. (5 March 2014). Dictionary of Real People and Places in Fiction. Routledge. ISBN 9781136119408.

- ^ "The Producers". IMDb. 10 November 1968.

- ^ Simonson, Robert (16 June 2002). "'When Will It Be Bloomsday?' June 16 at Symphony Space". Playbill.

- ^ "The Flickering Flame Lyrics". Roger Waters Web Ring. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Hunter, Jefferson (1980). "Orwell, Wells, and "Coming up for Air"". Modern Philology. 78 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1086/391004. ISSN 0026-8232. JSTOR 437247. S2CID 162037316.

- ^ ""A Man of Genius Makes No Mistakes": A Joycean Playlist Just in Time for Bloomsday 2015". FLOOD. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

External links

[edit]- "The Greatest Jew of all" : James Joyce, Leopold Bloom, and the Modernist Archetype, Morton P. Levitt, Papers on Joyce, 10/11 (2004–2005), pp. 143–162

- Ulysses Seen – ch. IV Calypso visualisation of Bloom in his first appearance in Ulysses

- John Henry Raleigh (1977). The Chronicle of Leopold and Molly Bloom: Ulysses as narrative. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03301-9.