Color depth

| Color depth |

|---|

| Related |

Color depth, also known as bit depth, is either the number of bits used to indicate the color of a single pixel, or the number of bits used for each color component of a single pixel. When referring to a pixel, the concept can be defined as bits per pixel (bpp). When referring to a color component, the concept can be defined as bits per component, bits per channel, bits per color (all three abbreviated bpc), and also bits per pixel component, bits per color channel or bits per sample (bps).[1][2][3] Modern standards tend to use bits per component,[1][2][4][5] but historical lower-depth systems used bits per pixel more often.

Color depth is only one aspect of color representation, expressing the precision with which the amount of each primary can be expressed; the other aspect is how broad a range of colors can be expressed (the gamut). The definition of both color precision and gamut is accomplished with a color encoding specification which assigns a digital code value to a location in a color space.

The number of bits of resolved intensity in a color channel is also known as radiometric resolution, especially in the context of satellite images.[6]

Comparison

[edit]- Same image on five different color depths, showing resulting (compressed) file sizes. 8 and smaller use an adaptive palette so quality may be better than some systems can provide.

-

8 bit.png 256 colors

37 KB (−62%) -

4 bit.png 16 colors

13 KB (−87%) -

2 bit.png 4 colors

6 KB (−94%) -

1 bit.png 2 colors

4 KB (−96%)

Indexed color

[edit]With the relatively low color depth, the stored value is typically a number representing the index into a color map or palette (a form of vector quantization). The colors available in the palette itself may be fixed by the hardware or modifiable by software. Modifiable palettes are sometimes referred to as pseudocolor palettes.

Old graphics chips, particularly those used in home computers and video game consoles, often have the ability to use a different palette per sprites and tiles in order to increase the maximum number of simultaneously displayed colors, while minimizing use of then-expensive memory (and bandwidth). For example, in the ZX Spectrum the picture is stored in a two-color format, but these two colors can be separately defined for each rectangular block of 8×8 pixels.

The palette itself has a color depth (number of bits per entry). While the best VGA systems only offered an 18-bit (262,144 color) palette[7][8][9][10] from which colors could be chosen, all color Macintosh video hardware offered a 24-bit (16 million color) palette. 24-bit palettes are nearly universal on any recent hardware or file format using them.

If instead the color can be directly figured out from the pixel values, it is "direct color". Palettes were rarely used for depths greater than 12 bits per pixel, as the memory consumed by the palette would exceed the necessary memory for direct color on every pixel.

List of common depths

[edit]1-bit color

[edit]2 colors, often black and white direct color. Sometimes 1 meant black and 0 meant white, the inverse of modern standards. Most of the first graphics displays were of this type, the X Window System was developed for such displays, and this was assumed for a 3M computer. In the late 1980s there were professional displays with resolutions up to 300 dpi (the same as a contemporary laser printer) but color proved more popular.

2-bit color

[edit]4 colors, usually from a selection of fixed palettes. Gray-scale early NeXTstation, color Macintoshes, Atari ST medium resolution.

3-bit color

[edit]8 colors, almost always all combinations of full-intensity red, green, and blue. Many early home computers with TV displays, including the ZX Spectrum and BBC Micro.

4-bit color

[edit]16 colors, usually from a selection of fixed palettes. Used by IBM CGA (at the lowest resolution), EGA, and by the least common denominator VGA standard at higher resolution. Color Macintoshes, Atari ST low resolution, Commodore 64, and Amstrad CPCs also supported 4-bit color.

5-bit color

[edit]32 colors from a programmable palette, used by the Original Amiga chipset.

6-bit color

[edit]64 colors. Used by the Master System, Enhanced Graphics Adapter, GIME for TRS-80 Color Computer 3, Pebble Time smartwatch (64 color e-paper display), and Parallax Propeller using the reference VGA circuit.

8-bit color

[edit]256 colors, usually from a fully-programmable palette: Most early color Unix workstations, Super VGA, color Macintosh, Atari TT, Amiga AGA chipset, Falcon030, Acorn Archimedes. Both X and Windows provided elaborate systems to try to allow each program to select its own palette, often resulting in incorrect colors in any window other than the one with focus.

Some systems placed a color cube in the palette for a direct-color system (and so all programs would use the same palette). Usually fewer levels of blue were provided than others, since the normal human eye is less sensitive to the blue component than to either red or green (two thirds of the eye's receptors process the longer wavelengths[11]). Popular sizes were:

- 6×6×6 (web-safe colors), leaving 40 colors for a gray ramp, or for programmable palette entries.

- 8×8×4. 3 bits of R and G, 2 bits of B, the correct value can be computed from a color without using multiplication. Used, among others, in the MSX2 system series of computers.

- a 6×7×6 color cube, leaving 4 colors for a programmable palette or grays.

- a 6×8×5 cube, leaving 16 colors for a programmable palette or grays.

12-bit color

[edit]4,096 colors, usually from a fully-programmable palette (though it was often set to a 16×16×16 color cube). Some Silicon Graphics systems, Color NeXTstation systems, and Amiga systems in HAM mode have this color depth.

RGBA4444, a related 16 bpp representation providing the color cube and 16 levels of transparency, is a common texture format in mobile graphics.

High color (15/16-bit)

[edit]In high-color systems, two bytes (16 bits) are stored for each pixel. Most often, each component (R, G, and B) is assigned 5 bits, plus one unused bit (or used for a mask channel or to switch to indexed color); this allows 32,768 colors to be represented. However, an alternate assignment which reassigns the unused bit to the G channel allows 65,536 colors to be represented, but without transparency.[12] These color depths are sometimes used in small devices with a color display, such as mobile phones, and are sometimes considered sufficient to display photographic images.[13] Occasionally 4 bits per color are used plus 4 bits for alpha, giving 4,096 colors. Among the first hardware to use the standard were the Sharp X68000 and IBM's Extended Graphics Array (XGA).

The term "high color" has recently been used to mean color depths greater than 24 bits.

18-bit

[edit]Almost all of the least expensive LCDs (such as typical twisted nematic types) provide 18-bit color (64×64×64 = 262,144 combinations) to achieve faster color transition times, and use either dithering or frame rate control to approximate 24-bit-per-pixel true color,[14] or throw away 6 bits of color information entirely. More expensive LCDs (typically IPS) can display 24-bit color depth or greater.

True color (24-bit)

[edit]

24 bits almost always use 8 bits each of R, G, and B (8 bpc). As of 2018, 24-bit color depth is used by virtually every computer and phone display [citation needed] and the vast majority of image storage formats. Almost all cases of 32 bits per pixel assigns 24 bits to the color, and the remaining 8 are the alpha channel or unused.

224 gives 16,777,216 color variations. The human eye can discriminate up to ten million colors,[15] and since the gamut of a display is smaller than the range of human vision, this means this should cover that range with more detail than can be perceived. However, displays do not evenly distribute the colors in human perception space, so humans can see the changes between some adjacent colors as color banding. Monochromatic images set all three channels to the same value, resulting in only 256 different colors; some software attempts to dither the gray level into the color channels to increase this, although in modern software this is more often used for subpixel rendering to increase the space resolution on LCD screens where the colors have slightly different positions.

The DVD-Video and Blu-ray Disc standards support a bit depth of 8 bits per color in YCbCr with 4:2:0 chroma subsampling.[16][17] YCbCr can be losslessly converted to RGB.

MacOS refers to 24-bit colour as "millions of colours". The term true colour is sometimes used to mean what this article is calling direct colour.[18] It is also often used to refer to all color depths greater or equal to 24.

Deep color (30-bit)

[edit]Deep color consists of a billion or more colors.[19] 230 is 1,073,741,824. Usually this is 10 bits each of red, green, and blue (10 bpc). If an alpha channel of the same size is added then each pixel takes 40 bits.

Some earlier systems placed three 10-bit channels in a 32-bit word, with 2 bits unused (or used as a 4-level alpha channel); the Cineon file format, for example, used this. Some SGI systems had 10- (or more) bit digital-to-analog converters for the video signal and could be set up to interpret data stored this way for display. BMP files define this as one of its formats, and it is called "HiColor" by Microsoft.

Video cards with 10 bits per component started coming to market in the late 1990s. An early example was the Radius ThunderPower card for the Macintosh, which included extensions for QuickDraw and Adobe Photoshop plugins to support editing 30-bit images.[20] Some vendors call their 24-bit color depth with FRC panels 30-bit panels; however, true deep color displays have 10-bit or more color depth without FRC.

The HDMI 1.3 specification defines a bit depth of 30 bits (as well as 36 and 48 bit depths).[21] In that regard, the Nvidia Quadro graphics cards manufactured after 2006 support 30-bit deep color[22] and Pascal or later GeForce and Titan cards when paired with the Studio Driver[23] as do some models of the Radeon HD 5900 series such as the HD 5970.[24][25] The ATI FireGL V7350 graphics card supports 40- and 64-bit pixels (30 and 48 bit color depth with an alpha channel).[26]

The DisplayPort specification also supports color depths greater than 24 bpp in version 1.3 through "VESA Display Stream Compression, which uses a visually lossless low-latency algorithm based on predictive DPCM and YCoCg-R color space and allows increased resolutions and color depths and reduced power consumption."[27]

At WinHEC 2008, Microsoft announced that color depths of 30 bits and 48 bits would be supported in Windows 7, along with the wide color gamut scRGB.[28][29]

High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC or H.265) defines the Main 10 profile, which allows for 8 or 10 bits per sample with 4:2:0 chroma subsampling.[2][4][5][30][31] The Main 10 profile was added at the October 2012 HEVC meeting based on proposal JCTVC-K0109 which proposed that a 10-bit profile be added to HEVC for consumer applications.[5] The proposal stated that this was to allow for improved video quality and to support the Rec. 2020 color space that will be used by UHDTV.[5] The second version of HEVC has five profiles that allow for a bit depth of 8 bits to 16 bits per sample.[32]

As of 2020, some smartphones have started using 30-bit color depth, such as the OnePlus 8 Pro, Oppo Find X2 & Find X2 Pro, Sony Xperia 1 II, Xiaomi Mi 10 Ultra, Motorola Edge+, ROG Phone 3 and Sharp Aquos Zero 2.[citation needed]

36-bit

[edit]Using 12 bits per color channel produces 36 bits, 68,719,476,736 colors. If an alpha channel of the same size is added then there are 48 bits per pixel.

48-bit

[edit]Using 16 bits per color channel produces 48 bits, 281,474,976,710,656 colors. If an alpha channel of the same size is added then there are 64 bits per pixel.

Image editing software such as Adobe Photoshop started using 16 bits per channel fairly early in order to reduce the quantization on intermediate results (i.e. if an operation is divided by 4 and then multiplied by 4, it would lose the bottom 2 bits of 8-bit data, but if 16 bits were used it would lose none of the 8-bit data). In addition, digital cameras are able to produce 10 or 12 bits per channel in their raw data; as 16 bits is the smallest addressable unit larger than that, using it would make it easier to manipulate the raw data.

Expansions

[edit]High dynamic range and wide gamut

[edit]Some systems started using those bits for numbers outside the 0–1 range rather than for increasing the resolution. Numbers greater than 1 were for colors brighter than the display could show, as in high-dynamic-range imaging (HDRI). Negative numbers can increase the gamut to cover all possible colors, and for storing the results of filtering operations with negative filter coefficients. The Pixar Image Computer used 12 bits to store numbers in the range [-1.5, 2.5), with 2 bits for the integer portion and 10 for the fraction. The Cineon imaging system used 10-bit professional video displays with the video hardware adjusted so that a value of 95 was black and 685 was white.[33] The amplified signal tended to reduce the lifetime of the CRT.

Linear color space and floating point

[edit]More bits also encouraged the storage of light as linear values, where the number directly corresponds to the amount of light emitted. Linear levels makes calculation of computer graphics much easier. However, linear color results in disproportionately more samples near white and fewer near black, so the quality of 16-bit linear is about equal to 12-bit sRGB.

Floating point numbers can represent linear light levels spacing the samples semi-logarithmically. Floating point representations also allow for drastically larger dynamic ranges as well as negative values. Most systems first supported 32-bit per channel single-precision, which far exceeded the accuracy required for most applications. In 1999, Industrial Light & Magic released the open standard image file format OpenEXR which supported 16-bit-per-channel half-precision floating-point numbers. At values near 1.0, half precision floating point values have only the precision of an 11-bit integer value, leading some graphics professionals to reject half-precision in situations where the extended dynamic range is not needed.

More than three primaries

[edit]Virtually all television displays and computer displays form images by varying the strength of just three primary colors: red, green, and blue. For example, bright yellow is formed by roughly equal red and green contributions, with no blue contribution.

For storing and manipulating images, alternative ways of expanding the traditional triangle exist: One can convert image coding to use fictitious primaries, that are not physically possible but that have the effect of extending the triangle to enclose a much larger color gamut. An equivalent, simpler change is to allow negative numbers in color channels, so that the represented colors can extend out of the color triangle formed by the primaries. However these only extend the colors that can be represented in the image encoding; neither trick extends the gamut of colors that can actually be rendered on a display device.

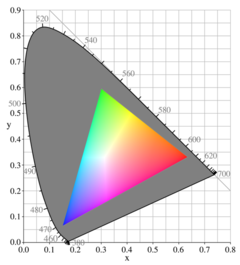

Supplementary colors can widen the color gamut of a display, since it is no longer limited to the interior of a triangle formed by three primaries at its corners, e.g. the CIE 1931 color space. Recent technologies such as Texas Instruments's BrilliantColor augment the typical red, green, and blue channels with up to three other primaries: cyan, magenta, and yellow.[34] Cyan would be indicated by negative values in the red channel, magenta by negative values in the green channel, and yellow by negative values in the blue channel, validating the use of otherwise fictitious negative numbers in the color channels.

Mitsubishi and Samsung (among others) use BrilliantColor in some of their TV sets to extend the range of displayable colors.[citation needed] The Sharp Aquos line of televisions has introduced Quattron technology, which augments the usual RGB pixel components with a yellow subpixel. However, formats and media that allow or make use of the extended color gamut are at present extremely rare.[citation needed]

Because humans are overwhelmingly trichromats or dichromats[b] one might suppose that adding a fourth "primary" color could provide no practical benefit. However humans can see a broader range of colors than a mixture of three colored lights can display. The deficit of colors is particularly noticeable in saturated shades of bluish green (shown as the left upper grey part of the horseshoe in the diagram) of RGB displays: Most humans can see more vivid blue-greens than any color video screen can display.

See also

[edit]- Audio bit depth – corresponding concept for digital audio

- Bit plane

- Image resolution

- List of color palettes

- List of colors (alphabetical)

- Mach banding

- RGB color model

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The cathode-ray tube monitor (CRT) is obsolete technology, but its more limited color-rendering clearly illustrates the problem that LCD monitors also have, despite their somewhat broader color gamut.

- ^ Some women have tested as functional tetrachromats but they are exceedingly rare.[citation needed] Less rare are "color blind" dichromats, who theoretically would only need two primary colors.

References

[edit]- ^ a b G.J. Sullivan; J.-R. Ohm; W.-J. Han; T. Wiegand (May 25, 2012). "Overview of the High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) Standard" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c G.J. Sullivan; Heiko Schwarz; Thiow Keng Tan; Thomas Wiegand (August 22, 2012). "Comparison of the Coding Efficiency of Video Coding Standards – Including High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC)" (PDF). IEEE Trans. on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "After Effects / Color basics". Adobe Systems. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) text specification draft 10 (for FDIS & Consent)". JCT-VC. January 17, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Alberto Dueñas; Adam Malamy (October 18, 2012). "On a 10-bit consumer-oriented profile in High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC)". JCT-VC. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Thenkabail, P. (2018). Remote Sensing Handbook - Three Volume Set. Remote Sensing Handbook. CRC Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4822-8267-2. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ US5574478A, Bril, Vlad & Pett, Boyd G., "VGA color system for personal computers", issued 1996-11-12

- ^ "Reading and writing 18-bit RGB VGA Palette (pal) files with C#". The Cyotek Blog. December 26, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "VGA/SVGA Video Programming--Color Registers". www.osdever.net. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "VGA Palette Conversion \ VOGONS". www.vogons.org. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "How we see color". Pantone (pantone.co.uk). Archived from the original on December 29, 2011.

- ^ Edward M. Schwalb (2003). iTV handbook: technologies and standards. Prentice Hall PTR. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-13-100312-5.

- ^ David A. Karp (1998). Windows 98 annoyances. O'Reilly Media. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-56592-417-8.

- ^ Kowaliski, Cyril; Gasior, Geoff; Wasson, Scott (July 2, 2012). "TR's Summer 2012 system guide". The Tech Report. p. 14. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ D. B. Judd and G. Wyszecki (1975). Color in Business, Science and Industry. Wiley Series in Pure and Applied Optics (third ed.). New York: Wiley-Interscience. p. 388. ISBN 0-471-45212-2.

- ^ Clint DeBoer (April 16, 2008). "HDMI Enhanced Black Levels, xvYCC and RGB". Audioholics. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ "Digital Color Coding" (PDF). Telairity. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 7, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ Charles A. Poynton (2003). Digital Video and HDTV. Morgan Kaufmann. p. 36. ISBN 1-55860-792-7.

- ^ Jack, Keith (2007). Video demystified: a handbook for the digital engineer (5th ed.). Newnes. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-7506-8395-1.

- ^ "Radius Ships ThunderPower 30/1920 Graphics Card Capable of Super Resolution 1920 × 1080 and Billions of Colors". Business Wire. August 5, 1996.

- ^ "HDMI Specification 1.3a Section 6.7.2". HDMI Licensing, LLC. November 10, 2006. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ "Chapter 32. Configuring Depth 30 Displays (driver release notes)". NVIDIA.

- ^ "NVIDIA Studio Driver 431.70 (Release Highlights)". NVIDIA.

- ^ "ATI Radeon HD 5970 Graphics Feature Summary". AMD. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ "AMD's 10-bit Video Output Technology" (PDF). AMD. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Tony (March 20, 2006). "ATI unwraps first 1GB graphics card". Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ^ "Looking for a HDMI 2.0 displayport to displayport for my monitor". Tom's Hardware. [Solved] - Displays. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "WinHEC 2008 GRA-583: Display Technologies". Microsoft. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ "Windows 7 High Color Support". Softpedia. November 26, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Furgusson, Carl (June 11, 2013). "HEVC: The background behind the game-changing standard- Ericsson". Focus on ... Ericsson. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ Forrest, Simon (June 20, 2013). "The emergence of HEVC and 10-bit colour formats". Imagination Technologies. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ Boyce, Jill; Chen, Jianle; Chen, Ying; Flynn, David; Hannuksela, Miska M.; Naccari, Matteo; et al. (July 11, 2014). "Draft high efficiency video coding (HEVC) version 2, combined format range extensions (RExt), scalability (SHVC), and multi-view (MV-HEVC) extensions". JCT-VC. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ "8-bit vs. 10-bit Color Space" (PDF). January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Hutchison, David (April 5, 2006). "Wider color gamuts on DLP display systems through BrilliantColor technology". Digital TV DesignLine. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.