Coronado, California

Coronado, California | |

|---|---|

Hotel del Coronado in December 2008 | |

| Nickname: "The Crown City" | |

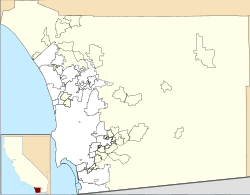

Location of Coronado in San Diego County, California | |

| Coordinates: 32°40′41″N 117°10′21″W / 32.67806°N 117.17250°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | December 11, 1890[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Richard Bailey (R)[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 32.50 sq mi (84.17 km2) |

| • Land | 7.80 sq mi (20.22 km2) |

| • Water | 24.69 sq mi (63.96 km2) 75.72% |

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 20,192 |

| • Density | 2,587.06/sq mi (998.82/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 92118, 92178 |

| Area code | 619 |

| FIPS code | 06-16378 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1660513, 2410233 |

| Website | www |

Coronado (Spanish for "Crowned") is a resort city in San Diego County, California, United States, across San Diego Bay from downtown San Diego.[5] It was founded in the 1880s and incorporated in 1890. Its population was 20,192 in 2020,[6] down from 24,697 in 2010.[7][8]

Coronado is a tied island which is connected to the mainland by a tombolo (a sandy isthmus) called Silver Strand. Along the coast of Southern California lie four islands that were spotted by Sebastian Vizcaino and his crew. They named them "Los Coronados". In the mid-1880s, businessmen bought the peninsula near Los Coronados with hopes to turn it into a resort. Later in 1886, the owners of this peninsula hosted a naming contest with the people resulting in the name "Miramar" winning, which was soon overturned due to the public not being satisfied with the name, so they borrowed from their cousin islands "Los Coronados" and named it "Coronado".[9] The explorer Sebastian Vizcaino drew its first map in 1602. Coronado is the Spanish term for "crowned" and thus it is nicknamed The Crown City. Its name is derived from the Coronado Islands, an offshore Mexican archipelago.[10] Three ships of the United States Navy have been named after the city, including USS Coronado.

History

[edit]Prior to European settlement, Coronado was inhabited by the Kumeyaay, who sustained fishing villages on the peninsula in North Island and on the Coronado Cays. As American settlers moved into the area, the Kumeyaay were pushed out of Coronado, with the last six Kumeyaay families deported to Mesa Grande Reservation in 1902.[11]

Coronado was incorporated as a town on December 11, 1890. The community's first post office predates Coronado's incorporation, established on February 8, 1887, with Norbert Moser assigned as the first postmaster.[10] The land was purchased by Elisha Spurr Babcock, Hampton L. Story, and Jacob Gruendike. Their intention was to create a resort community, and in 1886, the Coronado Beach Company was organized. By 1888, they had built Hotel del Coronado, and the city became a major resort destination. They also built a schoolhouse and formed athletic, boating, and baseball clubs.

In 1900, a tourist/vacation area just south of Hotel del Coronado was established by John D. Spreckels and named Tent City. Spreckels also became the hotel's owner.[12] Over the years, the tents gave way to cottages, the last of which was torn down in late 1940 or early 1941.

In the 1910s, Coronado had streetcars running on Orange Avenue. These streetcars became a fixture of the city until their retirement in 1939.[13]

What is now the Naval Air Station North Island was the first US flying school, founded in 1911 by Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss was known for his engines, which set records in distance and speed. He started with motorcycle engines, which led him to aviation. Coronado's weather and protected bay were attractive and he gained a three-year lease to train military pilots.[14] During this time he created a new type of ship-launched seaplane and an amphibious aircraft.[15]

On New Year's Day 1937, during the Great Depression, the gambling ship SS Monte Carlo, known for "drinks, dice, and dolls", was shipwrecked on the beach about a quarter mile (400 m) south of Hotel del Coronado.[16]

In 1946, an African-American man from Coronado named Alton Collier was forced off of a San Diego and Coronado ferry by white sailors. The case was ruled a suicide until 2024, when the Equal Justice Initiative declared a lynching.[17][18]

In 1969, the San Diego–Coronado Bridge was opened, allowing much faster transit between the cities than bay ferries or driving via State Route 75 along the Silver Strand. The bridge is made up of five lanes, one of which is controlled by a moveable barrier that allows for better traffic flow during rush hours. In the morning, the lane is moved to create three lanes going southbound towards Coronado, and in the evening it is moved again to create three lanes going northbound towards downtown San Diego.[19]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 32.7 square miles (85 km2); 7.9 square miles (20.5 km2) of the city is land and 24.7 square miles (64 km2) of it (75.72%) is water.

Geographically, Coronado is a tied island connected to the mainland by a tombolo known as the Silver Strand. The Silver Strand, Coronado and North Island, form San Diego Bay. Since recorded history, Coronado was mostly separated from North Island by a shallow inlet of water called the Spanish Bight. The development of North Island by the United States Navy prior to and during World War II led to the filling of the bight by July 1944, combining the land areas into a single body.[20] The Navy still operates Naval Air Station North Island (NASNI or "North Island") on Coronado. On the southern side of the town is Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, a training center for Navy SEALs and Special warfare combatant-craft crewmen (SWCC). Both facilities are part of the larger Naval Base Coronado complex. Coronado has increased in size due to dredge material being dumped on its shoreline and through the natural accumulation of sand. The "Country Club" area on the northwest side of Coronado, the "Glorietta" area and golf course on the southeast side of Coronado, most of the Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, most of the Strand Naval Housing, and most of the Coronado Cays (all on the south side of Coronado) were built on dirt dredged from San Diego Bay.

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen climate classification system, Coronado has a semi-arid climate, abbreviated BSk on climate maps.[21]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 276 | — | |

| 1870 | 229 | −17.0% | |

| 1900 | 935 | — | |

| 1910 | 1,477 | 58.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,289 | 122.7% | |

| 1930 | 5,425 | 64.9% | |

| 1940 | 6,932 | 27.8% | |

| 1950 | 12,700 | 83.2% | |

| 1960 | 18,039 | 42.0% | |

| 1970 | 20,020 | 11.0% | |

| 1980 | 18,790 | −6.1% | |

| 1990 | 26,540 | 41.2% | |

| 2000 | 24,100 | −9.2% | |

| 2010 | 24,697 | 2.5% | |

| 2020 | 20,192 | −18.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census reported that the City of Coronado had a population of 24,697.[23] The racial makeup of Coronado was 20,074 (81.2%) White, 1,678 (6.8%) African American, 201 (0.8%) Native American, 925 (3.7%) Asian, 101 (0.4%) Pacific Islander, 762 (3.1%) from other races, and 956 (3.9%) from two or more races. There were 3,354 Hispanic or Latino residents, of any race (13.6%).[7][8]

2000

[edit]As of the 2000 census,[24] there were 24,100 people, 7,734 households, and 4,934 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,121.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,205.4/km2). There were 9,494 housing units at an average density of 1,229.8 per square mile (474.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 84.40% White, 5.15% African American, 0.66% Native American, 3.72% Asian, 0.30% Pacific Islander, 3.14% from other races, and 2.63% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 9.83% of the population.

There were 7,734 households, out of which 27.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.0% were married couples living together, 7.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.2% were non-families. 30.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the city, 16.0% of the population was under the age of 18, 20.2% from 18 to 24, 29.3% from 25 to 44, 18.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.8% was 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 139.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 149.1 males.

48.2% of those aged 25 and over had a bachelor's degree or higher. According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $91,748,[25] and the median income for a family was $119,205.[26]

Real estate in the city of Coronado is very expensive. According to a recent county-wide ZIP code chart published in The San Diego Union-Tribune in August 2006, the median cost of a single-family home within the city's ZIP code of 92118 was $1,605,000. In 2010, Forbes.com found that the median home price in Coronado had risen to $1,840,665.[27]

By 2023, the median home value was $2.2 million, with more than a quarter of households earning more than $200,000.[28]

Government and politics

[edit]Coronado is governed by a city council, which is presided over by a directly elected mayor. The mayor and councilmembers serve four-year terms. Council designates one of its members as Mayor Pro Tempore.[29]

Coronado has long been a Republican stronghold; in 2013, about 47% of voters were registered Republican, 25% Democratic, and 24% nonpartisan.[30]

Prior to 2020, the resort city had voted for the Republican nominee in each presidential election since at least 1964. From 1968 to 1988, each Republican presidential candidate received over 70% of the vote. However the city has been trending Democratic in recent years, with each of the last four Republican presidential candidates receiving less than 60% of the vote. In 2016, Donald Trump won Coronado with a plurality of the vote, and Hillary Clinton received the largest share of the vote for a Democratic candidate since at least 1960.[31] In 2020, Democratic nominee and former vice president Joe Biden won Coronado with 51.50% of the vote, becoming the first Democratic presidential nominee to carry the city in decades. This result was nevertheless significantly lower than his statewide vote share of 63.48%.

In the California State Legislature, Coronado is in the 39th Senate District, represented by Democrat Akilah Weber, and in the 78th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Chris Ward.[32] In the United States House of Representatives, Coronado is located in California's 50th congressional district, which has a Cook partisan voting index of D+14[33] and is represented by Democrat Scott Peters.[34]

After California state law mandated that localities zone for affordable housing across the state, Coronado refused to comply with the law.[28] Coronado mayor Richard Bailey described the housing development as "central planning at its worst" and refused to submit a housing plan that allows for construction of the required amount of homes.[28]

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020[35] | 51.50% 5,308 | 44.39% 4,575 | 4.11% 424 |

| 2016[31] | 45.90% 4,024 | 48.06% 4,213 | 6.05% 530 |

| 2012[36] | 39.04% 3,455 | 59.10% 5,230 | 1.85% 164 |

| 2008[37] | 41.73% 3,855 | 56.94% 5,260 | 1.33% 123 |

| 2004[38] | 36.26% 3,326 | 62.93% 5,773 | 0.81% 74 |

| 2000[39] | 32.39% 2,823 | 63.74% 5,556 | 3.87% 337 |

| 1996[40] | 31.16% 2,654 | 61.02% 5,197 | 7.82% 666 |

| 1992[41] | 26.99% 2,517 | 46.22% 4,310 | 26.78% 2,497 |

| 1988[42] | 27.21% 2,413 | 71.71% 6,360 | 1.08% 96 |

| 1984[43] | 21.86% 1,781 | 77.05% 6,278 | 1.09% 89 |

| 1980[44] | 18.09% 1,468 | 71.47% 5,799 | 10.44% 847 |

| 1976[45] | 27.87% 1,941 | 70.31% 4,897 | 1.82% 127 |

| 1972[46] | 23.50% 1,390 | 73.34% 4,338 | 3.16% 187 |

| 1968[47] | 24.27% 1,162 | 70.41% 3,371 | 5.33% 255 |

| 1964[48] | 36.86% 1,725 | 63.14% 2,955 |

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism is an essential component of Coronado's economy.[49] This city is home to three major resorts (Hotel del Coronado, Coronado Island Marriott, and Loews Coronado Bay Resort), as well as several other hotels and inns.[50] The downtown district along Orange Avenue, with its many shops, restaurants and theaters, is also a key part of the local economy. Many of the restaurants are highly rated and provide a wide variety of cuisine choices.[50]

Golf on Coronado started in 1897 with a nine hole golf course hosting the 1905 Southern California Open.[51] Later, golf on Coronado migrated to a new site in the Southern portion of the island with 18 holes designed by Jack Daray Sr..[52] Golf is a popular diversion on the island, entertaining 90,000 golf rounds annually.[53]

In 2008, the Travel Channel rated Coronado Beach as the sixth-best beach in America.[54]

Hotel del Coronado

[edit]

Hotel del Coronado, built in 1888, has been designated as a National Historic Landmark. Its guests have included American presidents George H. W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft, as well as Muhammad Ali, Jack Dempsey, Thomas Edison, Magic Johnson, Charles Lindbergh, Willie Mays, Babe Ruth, Oprah Winfrey, and Robert Downey. Actresses Mary Pickford and Marilyn Monroe also stayed here.

"The Del" has appeared in numerous works of popular culture and was said to have inspired the Emerald City in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. It is rumored that the city's main street, Orange Avenue, was Baum's inspiration for the yellow brick road. Other sources say Oz was inspired by the "White City" of the Chicago World's Fair of 1893.[55][56] Author L. Frank Baum would have been able to see the hotel from his front porch overlooking Star Park. Baum designed the crown chandeliers in the hotel's dining room.[57]

Once owned locally,[58] Hotel Del Coronado is now owned by Blackstone (60%), Strategic Hotels & Resorts Inc. (34.5%), and KSL Resorts (5.5%). When Strategic Hotels & Resorts Inc. bought its stake in 2006, the hotel was valued at $745 million; as of 2011, the hotel was valued at roughly $590 million.[59][60]

In popular culture

[edit]Scenes from Denzel Washington's film Antwone Fisher were shot in Coronado.[61] Parts of Brian De Palma's film Scarface and Ron Howard's film Splash were shot at Coronado Beach.[62] A film called Carbon featuring Whitney Wegman-Wood and Randy Davison was shot in Coronado near the restaurant Nado Republic.[63]

Schools

[edit]

Coronado Unified School District includes Coronado Middle School (CMS), Coronado High School, Silver Strand Elementary, and Village Elementary. Coronado School of the Arts, a public school-within-a-school, is located on the campus of Coronado High School. Among the city's private schools are Sacred Heart Parish School and Christ Church Day School.

Economy

[edit]Top employers

[edit]

According to the city's 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[64] the top 10 employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States Navy (Naval Air Station North Island, et al.) | 11,000–14,999 |

| 2 | Hotel del Coronado | 1,000–4,999 |

| 3 | Loews Coronado Bay Resort | 500–999 |

| 4 | Sharp Coronado Hospital | 500–999 |

| 5 | City of Coronado | 250–499 |

| 6 | Coronado Unified School District | 250–600 |

| 7 | Coronado Island Marriott Resort | 250–499 |

| 8 | BAE Systems | 100–249 |

| 9 | Peohe's | 100–249 |

| 10 | Realty Executives Dillon | 50–99 |

Notable people

[edit]

- Lisa Bruce – film producer

- Johnny Downs – child actor who played "Johnny" in the Our Gang series of short films from 1923 to 1926

- Christa Hastie – contestant on CBS Survivor Pearl Islands, Season 7, 2003[65]

- Lloyd Haynes – actor and television writer, known for TV series Room 222

- Mary Beardslee Hinds – American First Lady of Guam.

- Mae Hotely – silent film actress who appeared in 85 films between 1911 and 1929

- Jim Kelly – martial artist and actor, starred in Enter the Dragon with Bruce Lee

- Genai Kerr – U.S. Water Polo Olympian and NCAA All-American

- Anita Page – silent film actress

- Orville Redenbacher – popcorn marketer

- Sarah Roemer – actress and model, starred in 2007's Disturbia with Shia LaBeouf[66]

- Rodney Scott – Chief of United States Border Patrol[67]

- Tim Thomerson – actor and comedian, known for his portrayal of Jack Deth in the Trancers film series

- Wende Wagner – actress

- William Witney – film director[68]

Music

[edit]- Kevin Kenner – concert pianist

- Mojo Nixon – musician and radio host

- Nick Reynolds – founding member of The Kingston Trio

- George Sanger – video game music composer[69]

- Paul Sykes – singer

- Scott Weiland – former lead singer of Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver.[70]

- Tina Weymouth – bassist and vocalist of Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club

Commerce

[edit]- Charles T. Hinde – riverboat captain, businessman, original investor in Hotel del Coronado

- Doug Manchester – real estate developer and publisher of San Diego Union Tribune

- Orville Redenbacher – businessman behind eponymous brand of popcorn

- John D. Spreckels – transportation and real estate mogul

- Jonah Shacknai – (CEO of Medicis Pharmaceutical) and his girlfriend Rebecca Zahau[71]

- Ira C. Copley – publisher, politician, and utility tycoon[72]

Military

[edit]Army

[edit]- William P. Duvall, U.S. Army major general, retired to Coronado[73]

- Townsend Griffiss, first American airman killed in Europe following the United States's entry into World War II

Marine Corps

[edit]- General Joseph Henry Pendleton, USMC – Mayor of Coronado from 1928 to 1930, namesake of Camp Pendleton

- Major General John H. Russell Jr., USMC – 16th Commandant of the Marine Corps, son of Rear Admiral John Henry Russell, USN and father of Brooke Astor, noted philanthropist.

Navy

[edit]- Captain Ward Boston, USN – World War II Navy fighter pilot, then attorney for the Naval Board of Review which investigated the 1967 USS Liberty Incident

- Admiral Charles K. Duncan – USN Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

- Admiral Leon A. Edney – USN[74]

- Admiral Thomas B. Fargo, USN – inspiration for fictional Captain Bart Mancuso in film The Hunt for Red October

- Alfred Walton Hinds - Naval officer and Governor of Guam.

- John S. McCain Sr. – grandfather of Arizona senator and U.S. presidential candidate John McCain

- Admiral George Stephen Morrison, USN – father of The Doors' lead singer, Jim Morrison

- Commander Alan G. Poindexter, USN – NASA astronaut and Navy test pilot

- Rear Admiral Uriel Sebree, USN – made two Arctic expeditions, was the second acting governor of American Samoa, and served as commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet

- Commander Earl Winfield Spencer Jr., USN – first commanding officer of Naval Air Station San Diego

- Vice Admiral James Stockdale, USN – Medal of Honor recipient and 1992 candidate for vice president with Ross Perot

Politics and government

[edit]

- Brian Bilbray – Republican politician and member of the United States House of Representatives

- Alexander Butterfield – White House deputy assistant to Richard Nixon 1969–73, a key figure in Watergate scandal

- Don Davis – Florida politician

- Duncan Hunter – Congressman[75]

- M. Larry Lawrence – US Ambassador to Switzerland and owner of Hotel del Coronado

- Cindy Hensley McCain – wife of Sen. John McCain[76]

- John McCain – U.S. Senator and 2008 Republican presidential candidate[77]

- Nathan Oakes Murphy – Republican delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona Territory and 14th governor of the Territory

- Dana Rohrabacher – Republican politician and member of United States House of Representatives

- Donald Rumsfeld – former Secretary of Defense[78]

- George G. Siebels Jr. – first Republican mayor of Birmingham, Alabama, born in Coronado in 1913.

- Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, American-born wife of abdicated King Edward VIII of the United Kingdom

Sports

[edit]- Layne Beaubien – 2008 Olympic silver medalist in water polo

- Cam Cameron – offensive coordinator for NFL's Baltimore Ravens, San Diego Chargers

- Servando Carrasco – soccer player

- Chad Fox – Major League baseball pitcher for several teams, including Florida Marlins 2003 World Series championship team

- Ken Huff—former NFL player

- Fulton Kuykendall – former NFL player

- Jim Laslavic – former NFL linebacker

- Don Orsillo – play-by-play announcer for the San Diego Padres

- Gene Rock – former basketball player

- Sven Salumaa – former tennis player

- William Thayer Tutt – past president of International Ice Hockey Federation, member of Hockey Hall of Fame

Writers and poets

[edit]- L. Frank Baum – author of The Wizard of Oz, which in part was written while he resided on Coronado.

- Landis Everson – poet

References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "Coronado's Bachelor Mayor Up for Bid: Junior League Auctioning Dates". Times of San Diego. November 28, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Coronado". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Best places for the rich and single". CNN. July 13, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "Index of /programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/01-Redistricting_File--PL_94-171/California". www2.census.gov. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "2010 Census P.L. 94-171 Summary File Data". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "Census Bureau's acknowledgment or miscoding some of Coronado's & San Diego's census blocks" (PDF). Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ "The intriguing stories behind the names of some of San Diego's most well-known landmarks". San Diego Union-Tribune. December 10, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Salley, Harold E. (1977). History of California Post Offices, 1849-1976. The Depot. ISBN 0-9601558-1-3.

- ^ "Exhibit Recognizes Forgotten Chapter in History: Coronado's First Inhabitants, the Coastal Kumeyaay Indians". cdnc.ucr.edu. Coronado Eagle and Journal. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ "Unknown". Archived from the original on May 25, 2007.

- ^ "The Home of the San Diego Historic Class 1Streetcars". Sandiegohistoricstreetcars.org. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ "San Diego Air & Space Museum - Historical Balboa Park, San Diego". sandiegoairandspace.org. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ "San Diego Air & Space Museum - Historical Balboa Park, San Diego". sandiegoairandspace.org. Retrieved December 13, 2024.

- ^ Graham, David E (January 2, 2007). "Busting the House: Casino Boat Drashed into Coronado 70 Years Ago". SignOnSanDiego. San Diego: Union Tribune. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Deaderick, Lisa (May 26, 2024). "Coronado man's death ruled suicide in 1946, today recognized as 'racial terror lynching'". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ Hyson, Katie (May 24, 2024). "His San Diego death certificate says 'suicide.' Now he's being recognized as California's third lynching victim". KPBS Public Media. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- ^ "Inside the Icon: San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge". www.sandiegomagazine.com. August 25, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ Linder, Bruce (2001). San Diego's Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-55750-531-6.

- ^ "Coronado, California Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (December 10, 2013). "Corrected 2010 Census Total Population, Household Population, Group Quarters Population, Total Housing Unit, Occupied Housing Unit, and Vacant Housing Unit Counts for Governmental Units" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Site Map – Coronado Chamber of Commerce". Coronadochamber.com. June 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ "CNNMoney Ranks Coronado #8: Best Places for the Rich & Single – Coronado Island". money.cnn.com. August 17, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ Ewalt, David (September 27, 2010). "Forbes Luxury Housing Index". Forbes.

- ^ a b c "This exclusive island town might be California's biggest violator of affordable housing law". Los Angeles Times. April 18, 2023.

- ^ "Coronado California". Code Publishing Company. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ California Secretary of State. February 10, 2013 – Report of Registration Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved September 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "Supplement to the Statement of Vote Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). November 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "2022 Cook PVI: District Map and List". Cook Political Report. July 12, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ "California's 50th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote 2012, Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). November 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote 2008" (PDF). Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote (2004), Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote (2000), Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote - November, 5 1996 General election, Political Districts within Counties for President" (PDF). November 5, 1996. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Supplement to the Statement of Vote, General election" (PDF). November 3, 1992. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ "Statement of vote". 1968.

- ^ "Statement of vote". 1968.

- ^ "Statement of vote". 1968.

- ^ "Statement of vote". 1968.

- ^ "Statement of vote". 1968.

- ^ "California statement of vote". 1962.

- ^ "California statement of vote". 1962.

- ^ "Coronado Chamber of Commerce". Coronadochamber.com. June 21, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "California Resort Life". California Resort Life. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ "Coronado Golf & Its Champions (1897-1905)". Coronado Historical Association. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Greenwood, Trey (November 1, 2013). "Coronado Municipal Golf Course and the History of Golf on California's Coronado Island". Coronado Historical Association. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ Leornard, Tod (October 1, 2020). "Classic Course: San Diego's Beloved Coronado Golf Course". SCGA Fore Magazine. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ "Top 10 Beaches in America". Travel Channel. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ "Chicago Tribune, August 30, 2009". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 2, 2009.

- ^ Larson, Erik, The Devil in the White City, page 373, Vintage Books, New York, 2003, ISBN 0-375-72560-1

- ^ "Crown Room". KSL Resorts (Hotel del Coronado). Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Historic Hotel del Coronado acquired by Travelers affiliate". findarticles.com. Business Wire. September 12, 1996. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Chernikoff, Helen (February 7, 2011). "UPDATE 4-Blackstone takes 60 percent of Hotel del Coronado". Reuters. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Hudson, Kris (February 7, 2011). "Deal for Historic San Diego Hotel Adds Blackstone, Cashes Out KKR". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Benninger, Michael (March 1, 2016). "Hot Shots". Pacific San Diego Magazine. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "Spotlight on filming in SD County". Daily Times-Advocate. December 1, 1983. p. 57. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Manson, Bill (November 28, 2018). "Raul Urreola's night shoot". San Diego Reader. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ "City of Coronado Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). June 30, 2012. p. 154. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ "Survivor: Pearl Islands". www.cbsnews.com. August 28, 2003.

- ^ "San Diego Metropolitan – San Diego Scene – March 2002". Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Coronado's Rodney Scott Selected as Chief, U.S. Border Patrol". The Coronado Times. January 27, 2020.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (March 18, 2002). "Obituaries; William Witney, 86; B-Movie Action Director". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Patterson, Rob (June 16, 1995). "MIDI Pioneer George Alistair Sanger The Fat Man". www.austinchronicle.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ "San Diego CityBeat – They fought the law". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Davis, Kristina; Littlefield, Dana; Repart, Pauline (September 2, 2011), "Shacknai, family speak out on mansion suicide ruling", San Diego Union-Tribune, retrieved September 9, 2011

- ^ Selgi-Harrigan, Alessandra (December 15, 2015). "From Mansion To Hotel, The Glorietta Bay Inn Remains A Landmark". Coronado Eagle & Journal. Coronado, CA. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ Thayer, Bill (March 28, 2014). "William Penn Duvall in Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, Volumes III-VI". Bill Thayer's Web Site. Chicago, IL: Bill Thayer. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "LEON A EDNEY – CORONADO, CA 92118 – Money, Government Contracts in 2004–1037 ENCINO ROW". Governmentcontractswon.com. January 13, 2004. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Hunter got break on taxes for home. San Diego Union Tribune, October 8, 2006.

- ^ Turegano, Preston. "Cindy McCain – San Diego Magazine – August 2007 – San Diego, California". San Diego Magazine. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (May 3, 2007). "G.O.P. Contenders Ponder What to Say About Bush". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ "DefenseLink News Transcript: Secretary Rumsfeld Interview with Roger Hedgecock, Newsradio 600 KOGO". Defenselink.mil. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- A Timeline of Coronado History - Coronado Historical Association and Coronado Museum

- The Coronado Times Newspaper - Newspaper covering news, events, sports and people of Coronado, CA.