Transnistria

Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Мы славим тебя, Приднестровье My slavim tebya, Pridnestrovie "We Sing the Praises of Transnistria"[2] | |

| |

| Status | Unrecognized state |

| Capital and largest city | Tiraspol 46°50′25″N 29°38′36″E / 46.84028°N 29.64333°E |

| Official languages | |

| Interethnic language | Russian[3][4][5] |

| Ethnic groups (2015) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Vadim Krasnoselsky | |

| Aleksandr Rozenberg | |

| Alexander Korshunov | |

| Legislature | Supreme Council |

| Establishment | |

• Independence from Moldavian SSR declared | 2 September 1990 |

• Independence from Soviet Union declared | 25 August 1991 |

• Succeeds the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic | 5 November 1991[6] |

| 2 March – 1 July 1992 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,163 km2 (1,607 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• March 2024 estimate | |

• 2015 census | |

• Density | 73.5/km2 (190.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | $1.201 billion[9] |

• Per capita | $2,584 |

| Currency | Transnistrian ruble |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Calling code | +373[a] |

| |

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie,[d] is a landlocked breakaway state internationally recognized as part of Moldova. It controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester river and the Moldova–Ukraine border, as well as some land on the other side of the river's bank. Its capital and largest city is Tiraspol. Transnistria is officially designated by the Republic of Moldova as the Administrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the Dniester (Romanian: Unitățile Administrativ-Teritoriale din stînga Nistrului)[10] or as Stînga Nistrului ("Left (Bank) of the Dniester").[11][12][13]

The region's origins can be traced to the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which was formed in 1924 within the Ukrainian SSR. During World War II, the Soviet Union took parts of the Moldavian ASSR, which was dissolved, and of the Kingdom of Romania's Bessarabia to form the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940. The present history of the region dates to 1990, during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was established in hopes that it would remain within the Soviet Union should Moldova seek unification with Romania or independence, the latter occurring in August 1991. Shortly afterwards, a military conflict between the two parties started in March 1992 and concluded with a ceasefire in July that year.

As a part of the ceasefire agreement, a three-party (Moldova, Russia, and Transnistria) Joint Control Commission and a trilateral peacekeeping force subordinated to the commission were created to deal with ceasefire violations.[14] Although the ceasefire has held, the territory's political status remains unresolved: Transnistria is an unrecognized but de facto independent semi-presidential republic[15] with its own government, parliament, military, police, postal system, currency, and vehicle registration.[16][17][18][19] Its authorities have adopted a constitution, flag, national anthem, and coat of arms. After a 2005 agreement between Moldova and Ukraine, all Transnistrian companies seeking to export goods through the Ukrainian border must be registered with the Moldovan authorities.[20] This agreement was implemented after the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM) took force in 2005.[21] In addition to the unrecognized Transnistrian citizenship, most Transnistrians have Moldovan citizenship,[22] but many also have Russian, Romanian, or Ukrainian citizenship.[23][24] The main ethnic groups are Russians, Moldovans/Romanians, and Ukrainians.

Transnistria, along with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, is a post-Soviet "frozen conflict" zone.[25] These three partially recognised or unrecognised states maintain friendly relations with each other and form the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations.[26][27][28]

In March 2022, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution that defines the territory as under military occupation by Russia.[29]

Toponymy

[edit]The region can also be referred to in English as Dniesteria, Trans-Dniester,[30] Transdniester[31] or Transdniestria.[32] These names are adaptations of the Romanian colloquial name of the region, Transnistria, meaning "beyond the Dniester".

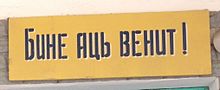

The term Transnistria was used in relation to eastern Moldova for the first time in the year 1989,[33][34][35] in the election slogan of the deputy and member of the Popular Front of Moldova Leonida Lari:[36][37][38]

I will throw out the invaders, aliens and mankurt over the Dniester, I will throw them out of Transnistria, and you, the Romanians, are the real owners of this long-suffering land ... We will make them speak Romanian, respect our language, our culture!

The documents of the government of Moldova refer to the region as Stînga Nistrului, meaning "Left (Bank) of the Dniester", or in full, Unitățile Administrativ-Teritoriale din Stînga Nistrului ("Administrative-territorial unit(s) of the Left Bank of the Dniester"). [39]

According to the Transnistrian authorities, the name of the state is the "Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic" (Russian: Приднестро́вская Молда́вская Респу́блика, romanized: Pridnestróvskaya Moldávskaya Respúblika; Romanian: Republica Moldovenească Nistreană, Moldovan Cyrillic: Република Молдовеняскэ Нистрянэ; Ukrainian: Придністро́вська Молда́вська Респу́бліка, romanized: Prydnistróvska Moldávska Respúblika). The short form is Pridnestrovie (Russian: Приднестровье, pronounced [prʲɪdʲnʲɪˈstrovʲje]; Romanian: Nistrenia, Moldovan Cyrillic: Нистрения,[40] pronounced [nistrenija]; Ukrainian: Придністров'я, romanized: Prydnistrovia, pronounced [predʲnʲiˈstrɔʋjɐ]), meaning "[land] by the Dniester".

The Supreme Council passed a law on 4 September 2024 which banned the use of the term Transnistria within the region, imposing a fine of 360 rubles or up to 15 days imprisonment for using the name in public.[41][42][43]

History

[edit]Soviet and Romanian administration

[edit]

In 1924, the Moldavian ASSR was proclaimed within the Ukrainian SSR. The ASSR included today's Transnistria (4,100 km2; 1,600 sq mi) and an area (4,200 km2; 1,600 sq mi) to the northeast around the city of Balta, but nothing from Bessarabia, which at the time formed part of the Kingdom of Romania. One of the reasons for the creation of the Moldavian ASSR was the desire of the Soviet Union at the time to eventually incorporate Bessarabia.[44] On 28 June 1940, the USSR annexed Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina from Romania under the terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and on 2 August 1940 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR created the Moldavian SSR by combining part of the annexed territory with part of the former Moldavian ASSR roughly equivalent to present-day Transnistria.

In 1941, after Axis forces invaded the Soviet Union in the Second World War, they defeated the Soviet troops in the region and occupied it. Romania controlled the entire region between Dniester and Southern Bug rivers, including the city of Odesa as local capital.[45] The Romanian-administered territory, known as the Transnistria Governorate, with an area of 39,733 km2 (15,341 sq mi) and a population of 2.3 million inhabitants, was divided into 13 counties: Ananiev, Balta, Berzovca, Dubasari, Golta, Jugastru, Movilau, Oceacov, Odessa, Ovidiopol, Rîbnița, Tiraspol, and Tulcin. This expanded Transnistria was home to nearly 200,000 Romanian-speaking residents. The Romanian administration of Transnistria attempted to stabilise the situation in the area under Romanian control, implementing a process of Romanianization.[46] During the Romanian occupation of 1941–44, between 150,000 and 250,000 Ukrainian and Romanian Jews were deported to Transnistria; the majority were murdered or died from other causes in the ghettos and concentration camps of the Governorate.[47]

After the Red Army advanced into the area in 1944, Soviet authorities executed, exiled or imprisoned hundreds of inhabitants of the Moldavian SSR in the following months on charges of collaboration with the Romanian occupiers. A later campaign directed against rich peasant families deported them to the Kazakh SSR and Siberia. Over the course of two days, 6–7 July 1949, a plan named "Operation South" saw the deportation of over 11,342 families by order of the Moldavian Minister of State Security, Iosif Mordovets.[48]

Secession

[edit]

In the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of perestroika and glasnost in the Soviet Union allowed political liberalisation at a regional level. This led to the creation of various informal movements all over the country, and to a rise of nationalism within most Soviet republics. In the Moldavian SSR in particular, there was a significant resurgence of pro-Romanian nationalism among Moldovans.[49] The most prominent of these movements was the Popular Front of Moldova (PFM). In early 1988, the PFM demanded that the Soviet authorities declare Moldovan the only state language, return to the use of the Latin alphabet, and recognise the shared ethnic identity of Moldovans and Romanians. The more radical factions of the PFM espoused extreme anti-minority, ethnocentric and chauvinist positions,[50][51] calling for minority populations, particularly the Slavs (mainly Russians and Ukrainians) and Gagauz, to leave or be expelled from Moldova.[52]

On 31 August 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR adopted Moldovan as the official language with Russian retained only for secondary purposes, returned Moldovan to the Latin alphabet, and declared a shared Moldovan-Romanian linguistic identity. As plans for major cultural changes in Moldova were made public, tensions rose further. Ethnic minorities felt threatened by the prospects of removing Russian as the official language, which served as the medium of interethnic communication, and by the possible future reunification of Moldova and Romania, as well as the ethnocentric rhetoric of the PFM. The Yedinstvo (Unity) Movement, established by the Slavic population of Moldova, pressed for equal status for both the Russian and Moldovan languages.[53] Transnistria's ethnic and linguistic composition differed significantly from most of the rest of Moldova. The proportion of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians was especially high and an overall majority of the population, some of them Moldovans, spoke Russian as their mother tongue.[54]

The nationalist PFM won the first free parliamentary elections in the Moldavian SSR in early 1990,[55] and its agenda started slowly to be implemented. On 2 September 1990, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (PMSSR) was proclaimed as a Soviet republic by an ad hoc assembly, the Second Congress of the Peoples' Representatives of Transnistria, following a successful referendum. Violence escalated when in October 1990 the PFM called for volunteers to form armed militias to stop an autonomy referendum in Gagauzia, which had an even higher proportion of ethnic minorities. In response, volunteer militias were formed in Transnistria. In April 1990, nationalist mobs attacked ethnic Russian members of parliament, while the Moldovan police refused to intervene or restore order.[56]

In the interest of preserving a unified Moldavian SSR within the USSR and preventing the situation escalating further, then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, while citing the restriction of civil rights of ethnic minorities by Moldova as the cause of the dispute, declared the Transnistria proclamation to be devoid of a legal basis and annulled it by presidential decree on 22 December 1990.[57][58] Nevertheless, no significant action was taken against Transnistria and the new authorities were slowly able to establish control of the region.

Following the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, the Pridnestrovian Moldavian SSR declared its independence from the Soviet Union. On 5 November 1991 Transnistria abandoned its socialist ideology and was renamed "Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic".[59]

Transnistria War

[edit]The Transnistria War followed armed clashes on a limited scale that broke out between Transnistrian separatists and Moldova as early as November 1990 at Dubăsari. Volunteers, including Cossacks, came from Russia to help the separatist side.[60] In mid-April 1992, under the agreements on the split of the military equipment of the former Soviet Union negotiated between the former 15 republics in the previous months, Moldova created its own Defence Ministry. According to the decree of its creation, most of the 14th Guards Army's military equipment was to be retained by Moldova.[61] Starting from 2 March 1992, there was concerted military action between Moldova and Transnistria. The fighting intensified throughout early 1992. The former Soviet 14th Guards Army entered the conflict in its final stage, opening fire against Moldovan forces;[61] approximately 700 people were killed. Moldova has since then exercised no effective control or influence on Transnistrian authorities. A ceasefire agreement, signed on 21 July 1992, has held to the present day.

Post-war period

[edit]

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is trying to facilitate a negotiated settlement. Under OSCE auspices, on 8 May 1997, Moldovan President Petru Lucinschi and Transnistrian President Igor Smirnov, signed the "Memorandum on the principles of normalization of relations between the Republic of Moldova and Transnistria", also known as the "Primakov Memorandum", sustaining the establishment of legal and state relations, although the memorandum's provisions were interpreted differently by the two governments.

In November 2003, Dmitry Kozak, a counselor of Russian president Vladimir Putin, proposed a memorandum on the creation of an asymmetric federal Moldovan state, with Moldova holding a majority and Transnistria being a minority part of the federation.[62] Known as "the Kozak memorandum", it did not coincide with the Transnistrian position, which sought equal status between Transnistria and Moldova, but gave Transnistria veto powers over future constitutional changes, thus encouraging Transnistria to sign it. Moldovan President Vladimir Voronin was initially supportive of the plan, but refused to sign it after internal opposition and international pressure from the OSCE and US, and after Russia had endorsed the Transnistrian demand to maintain a Russian military presence for the next 20 years as a guarantee for the intended federation.[63]

The 5+2 format (or 5+2 talks, comprising Transnistria, Moldova, Ukraine, Russia and the OSCE, plus the United States and the EU as external observers) for negotiation was started in 2005 to deal with the problems, but without results for many years as it was suspended. In February 2011, talks were resumed in Vienna,[64][65] continuing through to 2018 with some minor agreements being reached.[66] Moldova had, by 2023, dropped the term 5+2 in diplomatic discussions.

After the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in March 2014, the head of the Transnistrian parliament asked to join Russia.[67][68][69]

After the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Ukraine sealed its border with Transnistria, which had been the primary route for goods to enter the region. As such, Transnistria is wholly reliant on Moldova to allow imports through its own border. Transnistrian politicians have grown increasingly anxious about the situation, and in 2024 the Supreme Council was convened for the first time since 2006, with the council requesting economic assistance from Russia, and stating that Moldova was actively committing a genocide in the region.[70][71]

The harsh language towards Moldova, coupled with the Russian-backed Șor protests, and an attempted coup plotted by the Wagner Group has shifted Moldova further towards the European Union, and thus less likely to enter negotiations for economic relief from Transnistria.[70] Transnistria's request for "protection" from Russia alongside some calls for a referendum has led to suggestions that Russia may attempt to "annex" the region, as they did with occupied Ukraine in 2022.[72][73] On 1 January 2025 an agreement under which Russian gas was delivered via Ukraine ended, halting the flow of Russian gas to Transnistria and creating an energy and fiscal crisis. Transnistrian authorities have refused to purchase gas at market rates from Moldova, while Russia has not resumed delivery through an alternative route.[74]

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

Transnistria is landlocked and borders Bessarabia (the region the Republic of Moldova is based on, for 411 km; 255 mi) to the west, and Ukraine (for 405 km; 252 mi) to the east. It is a narrow valley stretching north–south along the bank of the Dniester river, which forms a natural boundary along most of the de facto border with Moldova.

The territory controlled by the PMR is mostly, but not completely, conterminous with the left (eastern) bank of Dniester. It includes ten cities and towns, and 69 communes, with a total of 147 localities (including here those unincorporated). Six communes on the left bank (Cocieri, Molovata Nouă, Corjova, Pîrîta, Coșnița, and Doroțcaia) remained under the control of the Moldovan government after the Transnistria War of 1992, as part of the Dubăsari District. They are situated north and south of the city of Dubăsari, which itself is under PMR control. The village of Roghi of Molovata Nouă Commune is also controlled by the PMR (Moldova controls the other nine of the 10 villages of the six communes).

On the west bank, in Bessarabia, the city of Bender (Tighina) and four communes (containing six villages) to its east, south-east, and south, on the opposite bank of the river Dniester from the city of Tiraspol (Proteagailovca, Gîsca, Chițcani, and Cremenciug) are controlled by the PMR.

The localities controlled by Moldova on the eastern bank, the village of Roghi, and the city of Dubăsari (situated on the eastern bank and controlled by the PMR) form a security zone along with the six villages and one city controlled by the PMR on the western bank, as well as two (Varnița and Copanca) on the same west bank under Moldovan control. The security situation inside it is subject to the Joint Control Commission rulings.

The main transportation route in Transnistria is the M4 road from Tiraspol to Rîbnița through Dubăsari. The highway is controlled in its entirety by the PMR.[75] North and south of Dubăsari it passes through land corridors controlled by Moldova in the villages of Doroțcaia, Cocieri, Roghi, and Vasilievca, the latter being located entirely to the east of the road. The road is the de facto border between Moldova and Transnistria in the area.[76] Conflict erupted on several occasions when the PMR prevented the villagers from reaching their farmland east of the road.[77][78]

Transnistrians are able to travel (normally without difficulty) in and out of the territory under PMR control to neighbouring Moldovan-controlled territory and to Ukraine. International air travellers rely on the airport in the Moldovan capital Chișinău, or the airport in Odesa, in Ukraine.

The climate is humid continental with subtropical characteristics. Transnistria has warm summers and cool to cold winters. Precipitation is unvarying all year round, although with a slight increase in the summer months.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Transnistria is subdivided into five districts (raions) and one municipality, the city of Tiraspol (which is entirely surrounded by but administratively distinct from Slobozia District), listed below from north to south (Russian names and transliterations are appended in parentheses). In addition, another municipality, the City of Bender, situated on the western bank of the Dniester, in Bessarabia, and geographically outside Transnistria, is not part of the territorial unit of Transnistria as defined by the Moldovan central authorities, but it is controlled by the PMR authorities, which consider it part of PMR's administrative organisation:

| Name | Capital | Area | Population (2015) | Ethnic composition (2004) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camenca District (Romanian: Camenca, Moldovan Cyrillic: Каменка) | Camenca | 436 square kilometres (168 sq mi) | 21,000 | 47.82% Moldovans, 42.55% Ukrainians, 6.89% Russians, 2.74% others |

| Rîbnița District (Romanian: Rîbnița, Moldovan Cyrillic: Рыбница) | Rîbnița | 850 square kilometres (330 sq mi) | 69,000 | 29.90% Moldovans, 45.41% Ukrainians, 17.22% Russians, 7.47% others |

| Dubăsari District (Romanian: Dubăsari, Moldovan Cyrillic: Дубэсарь) | Dubăsari | 381 square kilometres (147 sq mi) | 31,000 | 50.15% Moldovans, 28.29% Ukrainians, 19.03% Russians, 2.53% others |

| Grigoriopol District (Romanian: Grigoriopol, Moldovan Cyrillic: Григориопол) | Grigoriopol | 822 square kilometres (317 sq mi) | 40,000 | 64.83% Moldovans, 15.28% Ukrainians, 17.36% Russians, 2.26% others |

| Slobozia District (Romanian: Slobozia, Moldovan Cyrillic: Слобозия) | Slobozia | 873 square kilometres (337 sq mi) | 84,000 | 41.51% Moldovans, 21.71% Ukrainians, 26.51% Russians, 10.27% others |

| City of Tiraspol (Romanian: Tiraspol, Moldovan Cyrillic: Тираспол) | Tiraspol | 205 square kilometres (79 sq mi) | 129,000 | 18.41% Moldovans, 32.31% Ukrainians, 41.44% Russians, 7.82% others |

| City of Bender (Romanian: Tighina, Moldovan Cyrillic: Тигина/Бендер) | Bender | 97 square kilometres (37 sq mi) | 91,000 | 25.03% Moldovans, 17.98% Ukrainians, 43.35% Russians, 13.64% others |

Each of the districts is further divided into cities and communes.

Political status

[edit]

All UN member states consider Transnistria a legal part of the Republic of Moldova. Only the partially recognised or unrecognised states of South Ossetia and Abkhazia have recognised Transnistria as a sovereign entity after it declared independence from Moldova in 1990 with Tiraspol as its declared capital.

Between 1929 and 1940, Tiraspol functioned as the capital of the Moldavian ASSR, an autonomous republic that existed from 1924 to 1940 within the Ukrainian SSR.

Although exercising no direct control over the territory of Transnistria, the Moldovan government passed the "Law on Basic Provisions of the Special Legal Status of Localities from the Left Bank of the Dniester" on 22 July 2005, which established part of Transnistria (territory of Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic without Bender and without territories, which are under control of Moldova) as the Administrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the Dniester within the Republic of Moldova.

According to the 2004 census, the population of Transnistria comprised 555,347 people, while at the 2015 census the population decreased to 475,373. In 2004, 90% of the population of Transnistria were citizens of Transnistria.[79] Transnistrians may have dual, triple or even quadruple citizenship of internationally recognised countries, including:

- Citizens of Moldova:[80] around 300,000 people (including dual citizens of Moldova and Russia, around 20,000[81]) or of Moldova and the EU states (around 80%) of Romania,[82][83] Bulgaria, or the Czech Republic

- Citizens of Romania: unknown number[84]

- Citizens of Russia: around 150,000 people (including around 15,000 dual citizens of Belarus, Israel, Turkey); excluding those holding dual citizenship of Russia and of Moldova (around 20,000)

- Citizens of Ukraine: around 100,000 people[85] There are around 20,000–30,000 people with dual citizenship (Moldova and Ukraine, or Russia and Ukraine) or triple citizenship (Moldova, Russia and Ukraine). They are included in the number of Ukrainian citizens.[86]

- Persons without citizenship: around 20,000–30,000 people[citation needed]

Fifteen villages from the 11 communes of Dubăsari District, including Cocieri and Doroțcaia that geographically are located on the east bank of the Dniester (in Transnistria region), have been under the control of the central government of Moldova after the involvement of local inhabitants on the side of Moldovan forces during the War of Transnistria. These villages, along with Varnița and Copanca, near Bender and Tiraspol, are claimed by the PMR. One city (Bender) and six villages located on the west bank (in Bessarabia region) are controlled by the PMR, but are considered by Moldova as a separate municipality (Bender and village of Proteagailovca) or part of the Căușeni District (five villages in three communes).

Tense situations have periodically surfaced due to these territorial disputes, such as in 2005, when Transnistrian forces entered Vasilievca,[87] in 2006 around Varnița, and in 2007 in the Dubăsari-Cocieri area, when a confrontation between Moldovan and Transnistrian forces occurred, though without any casualties.

June 2010 surveys indicated that 13% of Transnistria's population desired the area's reintegration into Moldova in the condition of territorial autonomy, while 46% wanted Transnistria to be part of the Russian Federation.[88]

International relations

[edit]

Transnistria is a non-UN member state recognised as independent only by Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both being non-UN member states with limited recognition.

Nina Shtanski served as Transnistria's Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2012 to 2015; Vitaly Ignatiev succeeded her as minister. In 2024 Vitaly Ignatiev was declared wanted by the Security Service of Ukraine due to suspicion of collaboration and encroachment on the territorial integrity of Ukraine.[89]

Government and politics

[edit]

Transnistria is a semi-presidential republic with a powerful presidency. The president is directly elected for a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms. The current President is Vadim Krasnoselsky.

The Supreme Council is a unicameral legislature. It has 43 members who are elected for 5-year terms. Elections take place within a multi-party system.[90] The majority in the supreme council belongs to the Renewal movement that defeated the Republic party affiliated with Igor Smirnov in 2005 and performed even better in the 2010 and 2015 elections. Elections in Transnistria are not recognised by international bodies such as the European Union, as well as numerous individual countries, who called them a source of increased tensions.

There is disagreement over whether elections in Transnistria are free and fair. The political regime has been described as one of "super-presidentialism" before the 2011 constitutional reform.[91] During the 2006 presidential election, the registration of opposition candidate Andrey Safonov was delayed until a few days before the vote, so that he had little time to conduct an election campaign.[92][93] Some sources consider election results suspect. In 2001, in one region it was reported that Igor Smirnov collected 103.6% of the votes.[94] The PMR government said "the government of Moldova launched a campaign aimed at convincing international observers not to attend" an election held on 11 December 2005 – but monitors from the Russian-led Commonwealth of Independent States election monitors ignored that and declared the ballot democratic.

The opposition Narodovlastie party and Power to the People movement were outlawed at the beginning of 2000[95] and eventually dissolved.[96][97]

A list published by the European Union had banned travel to the EU for some members of the Transnistrian leadership.[98] Lifted by 2012.[99]

In 2007, the registration of a Social Democratic Party was allowed. This party, led by a former separatist leader and member of the PMR government Andrey Safonov, allegedly favours a union with Moldova.

In September 2007, the leader of the Transnistrian Communist Party, Oleg Khorzhan, was sentenced to a suspended sentence of 1½ years' imprisonment for organising unsanctioned actions of protest.[100]

According to the 2006 referendum, carried out by the PMR government, 97.2% of the population voted in favour of "independence from Moldova and free association with Russia".[101] EU and several other countries refused to recognise the referendum results.

Residents will have the opportunity to vote in Moldova's referendum on joining the EU, planned for autumn 2024. There will be no voting stations within Transnistria; however, residents will be free to travel into other areas of Moldova to vote, should they wish to.[102]

Transnistria border customs dispute

[edit]On 3 March 2006, Ukraine introduced new customs regulations on its border with Transnistria. Ukraine declared that it would import goods from Transnistria only with documents processed by Moldovan customs offices as part of the implementation of the joint customs protocol agreed between Ukraine and Moldova on 30 December 2005. Transnistria and Russia termed the act an "economic blockade".

The United States, the European Union, and the OSCE approved the Ukrainian move, while Russia saw it as a means of political pressure. On 4 March, Transnistria responded by blocking the Moldovan and Ukrainian transport at the borders of Transnistria. The Transnistrian block was lifted after two weeks. However, the Moldovan/Ukrainian block remains in place and holds up progress in status settlement negotiations between the sides.[103] In the months after the regulations, exports from Transnistria declined drastically. Transnistria declared a "humanitarian catastrophe" in the region, while Moldova called the declaration "deliberate misinformation".[104] Cargoes of humanitarian aid were sent from Russia in response.

Russian military presence in Transnistria

[edit]The 1992 cease-fire agreement between Moldova and Transnistria established a Russian "peacekeeper" presence in Transnistria and a 1,200-member Russian military contingent is present in Transnistria. Russian troops stationed in parts of Moldova except Transnistria since the time of the USSR were fully withdrawn to Russia by January 1993.

In April 1995, the Soviet 14th Guards Army became the Operational Group of Russian Forces, which by the 2010s had shrunk to two battalions and no more than 1,500 troops.

On 21 October 1994, Russia and Moldova signed an agreement that committed Russia to the withdrawal of the troops within three years of the agreement's effective date;[105] this did not come into effect, however, because the Russian Duma did not ratify it.[19] The Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) included a paragraph about the removal of Russian troops from Moldova's territory and was introduced into the text of the OSCE Summit Declaration of Istanbul (1999) in which Russia had committed itself to pulling out its troops from Transnistria by the end of 2002.[106] However, even after 2002, the Russian parliament did not ratify the Istanbul accords. On 19 July 2004, after it finally passed through parliament President Vladimir Putin signed the Law on the ratification of the CFE Treaty in Europe, which committed Russia to remove the heavy armaments limited by this Treaty.[107] During 2000–2001, although the CFE Treaty was not fully ratified, to comply with it, Moscow withdrew 125 pieces of Treaty Limited Equipment (TLE) and 60 railway wagons containing ammunition from the Transnistrian region of Moldova. In 2002, Russia withdrew three trainloads (118 railway wagons) of military equipment and two (43 wagons) of ammunition from the Transnistrian region of Moldova, and in 2003, 11 rail convoys transporting military equipment and 31 transporting ammunition. According to the OSCE Mission to Moldova, of a total of 42,000 tons of ammunition stored in Transnistria, 1,153 tons (3%) was transported back to Russia in 2001, 2,405 tons (6%) in 2002 and 16,573 tons (39%) in 2003.[citation needed]

Andrei Stratan, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Moldova, stated in his speech during the 12th OSCE Ministerial Council Meeting in Sofia on 6–7 December 2004 that "The presence of Russian troops on the territory of the Republic of Moldova is against the political will of Moldovan constitutional authorities and defies the unanimously recognized international norms and principles, being qualified by Moldovan authorities as a foreign military occupation illegally deployed on the territory of the state".[108][109] As of 2007[update] however, Russia insists that it has already fulfilled those obligations. It states the remaining troops are serving as peacekeepers authorised under the 1992 ceasefire, are not in violation of the Istanbul accords and will remain until the conflict is fully resolved.[110] On the other hand, Moldova believes that fewer than 500 soldiers are authorised pursuant to the ceasefire and, in 2015, began to arrest and deport Russian soldiers who are part of the excess forces and attempt to use Moldovan airports.[111]

In a NATO resolution on 18 November 2008, Russia was urged to withdraw its military presence from the "Transdnestrian region of Moldova".[112]

In 2011, US Senator John McCain claimed in a visit to Moldova that Moscow is violating the territorial integrity of Moldova and Georgia and one of the "fundamental norms" of "international behavior".[113] On 21 May 2015, the Ukrainian parliament passed a law terminating five co-operation agreements with Russia. This law effectively terminates the "Agreement on transit of Russian military units temporarily located on the territory of the Republic of Moldova through the territory of Ukraine" dated 4 December 1998.[111][114]

One point of access for Russian soldiers travelling to Transnistria remains Chișinău International Airport and the short overland journey from there to Tiraspol. Over the years, Moldova has largely permitted Russian officers and soldiers to transit the airport on their way to Transnistria, though occasionally it blocked those that were not clearly identified as international peacekeepers or who failed to give sufficient advance notice. Chișinău Airport would likely only ever agree to the possibility of moving employees, officers, and soldiers of the stationed forces. The passage of soldiers of the 14th Guards Army would be illegal.[115]

On 27 June 2016, a new law entered in force in Transnistria, punishing actions or public statements, including through the usage of mass media, networks of information and telecommunications or the Internet, criticising the military mission of the Russian Army stationed in Transnistria, or presenting interpretations perceived to be "false" by the Transnistrian government of the Russian Army's military mission. The punishment is up to three years of jail for ordinary people or up to seven years of jail if the crime was committed by a person of responsibility or a group of persons by prior agreement.[116][better source needed]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Transnistria declared it would maintain its neutrality in the situation and denied claims that it would assist in the attack on Ukraine.[117]

During the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian military intelligence stated on 14 January 2022 that they had evidence that the Russian government was covertly planning false flag "provocations" against Russian soldiers stationed in Transnistria, which would be used to justify a Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Russian government denied the claims.[118] In that prelude, similar unattributed clashes happened in Donbas in February 2022: Ukraine denied being involved in those incidents and called them a false flag operation as well.[119]

On 15 March 2022, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe recognised Transnistria as a Moldovan territory occupied by Russia.[29]

On 14 April 2022, one of Ukraine's deputy defence ministers, Hanna Maliar, stated that Russia was massing its troops along the borders with Transnistria but the Transnistrian authorities denied it.[120] According to the Transnistrian authorities, on April 25 there was an attack on the premises of the Ministry for State Security and on the next day two transmitting antennas broadcasting Russian radio programs at Grigoriopol transmitter near the Ukrainian border were blown up.[121] The Moldovan authorities called these events a provocation aimed at destabilising the situation in the region. The Russian army has a military base, a large ammunition dump and about 1,500 soldiers stationed in Transnistria, stating that they are there as "peacekeepers".[121]

Since the invasion of Ukraine, Transnistria has lost its economic connections with Ukraine and has had to rely and become more dependent on Moldova and trade links to the EU, resulting in an intensification of dialogue and collaboration, such as the help provided to Ukrainian refugees.[122]

Law

[edit]The legislation of Transnistria is classified into several areas:

- The Constitution,[123] a codex containing 28 consolidated legislative acts.

This area of legislation concerns the establishment of the Supreme Court, Arbitration Court, the Constitutional Court and the judicial and governmental system of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic. It also concerns the establishment of the statuses of some government officials, such as Judges, Deputies of the Supreme Council and the Prosecutors' Office. It also establishes a commissioner for human rights, special legal regimes, citizenship law, This category also contains amendments to the constitutional order, and its procedure to make alterations to the constitution.

- Laws relating to the foundational law and constitutional system,[124] a codex containing 81 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to the budget, finance, economic and taxation,[125] a codex containing 55 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to the judicial system and its procedures,[126] a codex containing 13 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to criminal, customs and administrative law,[127] a codex containing 12 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to the military and defence sector,[128] a codex containing 16 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to the civil, housing and family Law,[129] a codex containing 28 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to healthcare and social protection,[130] a codex containing 49 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to the field of agriculture and ecology,[131] A codex containing 28 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to industry, trade, privatisation, construction, transport, energy and communications,[132] a codex containing 42 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to education, culture, sports, youth policy, media, and implementation of political rights and freedoms of citizens,[133] a codex containing 43 legislative acts.

- Laws relating to government programs and government targeted programs,[134] a codex containing 20 legislative acts.

Military

[edit]

As of 2007[update], the armed forces and the paramilitary of Transnistria were composed of around 4,500–7,500 soldiers, divided into four motorised infantry brigades in Tiraspol, Bender, Rîbnița, and Dubăsari.[135] They have 18 tanks, 107 armoured personnel carriers, 73 field guns, 46 anti-aircraft installations, and 173 tank destroyer units.[136][137] The airforce is composed of 1 Mi-8T and 1 Mi-24 helicopter. Previous aircraft operated were Antonov An-26, Antonov An-2, and Yakovlev Yak-52 fixed wing and Mil Mi-2 and other Mi-8T and Mi-24 helicopters.[138]

Demographics

[edit]

2015 census

[edit]In October 2015, Transnistrian authorities organised another separate census from the 2014 Moldovan census.[139] According to the 2015 census, the population of the region was 475,373, a 14.5% decrease from the figure recorded in the 2004 census. The urbanisation rate was 69.9%. By ethnic composition, the population of Transnistria was distributed as follows: Russians – 29.1%, Moldovans – 28.6%, Ukrainians – 22.9%, Bulgarians – 2.4%, Gagauzians – 1.1%, Belarusians – 0.5%, Transnistrian – 0.2%, other nationalities – 1.4%. About 14% of the population did not declare their nationality. Also, for the first time, the population had the option to identify as "Transnistrian".[8]

According to another source, the largest ethnic groups in 2015 were 161,300 Russians (34%), 156,600 Moldovans (33%), and 126,700 Ukrainians (26.7%). Bulgarians comprised 13,300 (2.8%), Gagauz 5,700 (1.2%) and Belarusians 2,800 (0.6%). Germans accounted for 1,400 or 0.3% and Poles for 1,000 or 0.2%. Others accounted for 5,700 people or 1.2%.[140]

2004 census

[edit]In 2004, Transnistrian authorities organised a separate census from the 2004 Moldovan Census.[141] As per 2004 census, in the areas controlled by the PMR government, there were 555,347 people, including 177,785 Moldovans (32.1%) 168,678 Russians (30.4%) 160,069 Ukrainians (28.8%) 13,858 Bulgarians (2.5%) 4,096 Gagauzians (0.7%), 1,791 Poles (0.3%), 1,259 Jews (0.2%), 507 Roma (0.1%) and 27,454 others (4.9%).[142]

Of these, 439,243 lived in Transnistria itself, and 116,104 lived in localities controlled by the PMR government, but formally belonging to other districts of Moldova: the city of Bender (Tighina), the communes of Proteagailovca, Gîsca, Chițcani, Cremenciug, and the village of Roghi of commune Molovata Nouă.

Moldovans were the largest ethnic group, representing an overall majority in the two districts in the central Transnistria (Dubăsari District, 50.2%, and Grigoriopol District, 64.8%) a 47.8% relative majority in the northern Camenca District, and a 41.5% relative majority in the southern (Slobozia District). In Rîbnița District they were a 29.9% minority, and in the city of Tiraspol, they constituted a 15.2% minority of the population.

As per last census, Russians were the second largest ethnic group, representing a 41.6% relative majority in the city of Tiraspol, a 24.1% minority in Slobozia, a 19.0% minority in Dubăsari, a 17.2% minority in Râbnița, a 15.3% minority in Grigoriopol, and a 6.9% minority in Camenca.

Ukrainians were the third largest ethnic group, representing a 45.41% relative majority in the northern Rîbnița District, a 42.6% minority in Camenca, a 33.0% minority in Tiraspol, a 28.3% minority in Dubăsari, a 23.4% minority in Slobozia, and a 17.4% minority in Grigoriopol. A substantial number of Poles clustered in northern Transnistria were Ukrainianised during Soviet rule.

Bulgarians were the fourth largest ethnic group in Transnistria, albeit much less numerous than the three larger ethnicities. Most Bulgarians in Transnistria are Bessarabian Bulgarians, descendants of expatriates who settled in Bessarabia in the 18th–19th century. The major centre of Bulgarians in Transnistria is the large village of Parcani (situated between the cities of Tiraspol and Bender), which had an absolute Bulgarian majority and a total population of around 10,000.

In Bender (Tighina) and the other non-Transnistria localities under PMR control, ethnic Russians represented a 43.4% relative majority, followed by Moldovans at 26.2%, Ukrainians at 17.1%, Bulgarians at 2.9%, Gagauzians at 1.0%, Jews at 0.3%, Poles at 0.2%, Roma at 0.1%, and others at 7.8%.

1989 census

[edit]At the census of 1989, the population was 679,000 (including all the localities in the security zone, even those under Moldovan control). The ethnic composition of the region has been unstable in recent history, with the most notable change being the decreasing share of Moldovan and Jewish population segments and increase of the Russian. For example, the percentage of Russians grew from 13.7% in 1926 to 25.5% in 1989 and further to 30.4% in 2004, while the Moldovan population decreased from 44.1% in 1926 to 39.9% in 1989 and 31.9% in 2004. Only the proportion of Ukrainians remained reasonably stable – 27.2% in 1926, 28.3% in 1989 and 28.8% in 2004.

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tiraspol  Bender |

1 | Tiraspol | Tiraspol | 129,367 (2015 census) |  Rîbnița  Dubăsari | ||||

| 2 | Bender | Bender, Moldova | 91,197 (2015 census) | ||||||

| 3 | Rîbnița | Rîbnița District | 46,000 (2015 census) | ||||||

| 4 | Dubăsari | Dubăsari District | 23,650 (2004 census) | ||||||

| 5 | Slobozia | Slobozia District | 16,062 (2004 census) | ||||||

| 6 | Dnestrovsc | Slobozia District | 10,000 (2015 census) | ||||||

| 7 | Camenca | Camenca District | 10,323 (2004 census) | ||||||

| 8 | Grigoriopol | Grigoriopol District | 10,252 (2004 census) | ||||||

| 9 | Sucleia | Slobozia District | 10,001 (2004 census) | ||||||

| 10 | Parcani | Slobozia District | <8,000 (2004 census) | ||||||

Religion

[edit]

PMR official statistics show that 92% of the Transnistrian population adhere to Eastern Orthodox Christianity, with 4% adhering to Roman Catholicism.[144] Roman Catholics are mainly located in northern Transnistria, where a notable Polish minority lives.[145]

Transnistria's government has supported the restoration and construction of new Orthodox churches. It affirms that the republic has freedom of religion and states that 114 religious beliefs and congregations are officially registered. However, as recently as 2005, registration hurdles were met with by some religious groups, notably the Jehovah's Witnesses.[146] In 2007, the US-based Christian Broadcasting Network denounced the persecution of Protestants in Transnistria.[147]

Economy

[edit]Transnistria has a mixed economy. Following a large scale privatisation process in the late 1990s,[148] most of the companies in Transnistria are now privately owned. The economy is based on a mix of heavy industry (steel production), electricity production, and manufacturing (textile production), which together account for about 80% of the total industrial output.[149]

Transnistria has its own central bank, the Transnistrian Republican Bank, which issues its national currency, the Transnistrian ruble. It is convertible at a freely floating exchange rate but only in Transnistria.

Transnistria's economy is frequently described as dependent on contraband[150] and gunrunning.[151][152][153][better source needed] Some commentators, including Zbigniew Brzezinski, have even labelled it a mafia state.[154][155] These allegations are denied by the Transnistrian government, and sometimes downplayed by the officials of Russia and Ukraine.[156]

Economic history

[edit]After World War II, Transnistria was heavily industrialised, to the point that, in 1990, it was responsible for 40% of Moldova's GDP and 90% of its electricity,[157] although it accounted for only 17% of Moldova's population. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Transnistria wanted to return to a "Brezhnev-style planned economy".[158] However, several years later, it decided to head toward a market economy.

Macroeconomics

[edit]According to the government of Transnistria, the 2007 GDP was 6789 mln ruble (appx US$799 million) and the GDP per capita was about US$1,500. The GDP increased by 11.1% and inflation rate was 19.3% with the GDP per capita being $2,140, higher than the contemporaneous Moldovan GDP per capita of $2,040.[159] Transnistria's government budget for 2007 was US$246 million, with an estimated deficit of about US$100 million[160] that the government planned to cover with income from privatisations.[161] The budget for 2008 is US$331 million, with an estimated deficit of about US$80 million.[162]

In 2004, Transnistria had debts of US$1.2 billion (two-thirds are with Russia) that was per capita about six times higher than in Moldova (without Transnistria).[163] In March 2007 the debt to Gazprom for the acquisition of natural gas increased to US$1.3 billion. On 22 March 2007 Gazprom sold Transnistria's gas debt to the Russian businessman Alisher Usmanov, who controls Moldova Steel Works, the largest enterprise in Transnistria. Transnistria's president Igor Smirnov announced that Transnistria will not pay its gas debt because "Transnistria has no legal debt to Gazprom".[164][165] In November 2007, the total debt of Transnistria's public sector was up to US$1.64 billion.[162]

In the first half of 2023 the economic situation worsened with imports increasing 12% to $1.32 billion and exports falling by 10% to just $346m, the trade deficit of $970m, almost equal to the GDP of Transnistria in the whole of 2021, being financed by the non-payment of natural gas supplies from Russia.[166]

External trade

[edit]In 2020, the Transnistrian Customs reported exports of US$633.1 million and imports of US$1,052.7 million.[167] In the early 2000s over 50% of the export went to the CIS, mainly to Russia, but also to Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova (which Transnistrian authorities consider foreign).[148][149] Main non-CIS markets for the Transnistrian goods were Italy, Egypt, Greece, Romania, and Germany.[148] The CIS accounted for over 60% of the imports, while the share of the EU was about 23%. The main imports were non-precious metals, food products, and electricity.

After Moldova signed the Association Agreement with the EU in 2014, Transnistria – being claimed as part of Moldova – enjoyed the tariff-free exports to the EU. As a result, in 2015, 27% of Transnistria's US$189 million exports went to the EU, while exports to Russia went down to 7.7%. This shift towards the EU market continued to grow in 2016.[168]

From March 2022, with the Ukrainian border closed to Transnistria, all trade goods to and from Transnistria have needed to flow through Moldova, Transnistria now has to comply with Moldovan and EU standards when exporting products.[169] Transnistria reported on trade in the first half of 2023. 48% of exports were to the rest of Moldova, over 33% went to the EU and 9% to Russia. 68% of imports came from Russia, 14% from the EU and 7% from Moldova.[166]

In 2024 as a result of the free trade agreement between Moldova and the European Union, from which Transnistria also benefits, Moldova decided that imports/exports to/from Transnistria should be treated the same as imports/exports to/from Moldova, accordingly Transnistria importers wishing to import from/through Moldova must register and may, depending on the goods, be subject to taxes on imported goods, payable to Moldova.[170]

On the 30th of December 2024, Tirasteploenegro released a set of instructions - anticipating the expiration of Gazprom's deal with Ukraine, saying to only drain the pipes and batteries in emergencies, to close every tap that has been running (if the water supply dissapears) to avoid flooding when it turns back on, to "dress warmly", to avoid fires during Winter and Autumn, to not use gas or electric stoves for heating rooms as it may lead to tragedy, and to instead use factory-made electric heaters only; not home-made ones.[171]

On the New Year of 2025, Gazprom's deal with Ukraine to transport gas through it had expired, as Ukraine had refused to extend the deal, calling it a "historic moment".[172] This caused a severe gas shortage, and so only critical infrastructure was allowed to be heated, and houses were dropped from it to save on gas.[173]

The power plant in Kuchurgan, which is both Transnistria's and Moldova's main plant, is now also being fueled with coal, however the supply is only enough for 50 days.[174][173]

Economic sectors

[edit]The leading industry is steel, due to the Moldova Steel Works (part of the Russian Metalloinvest holding) in Rîbnița, which accounts for about 60% of the budget revenue of Transnistria.[101] The largest company in the textile industry is Tirotex, which claims to be the second largest textile company in Europe.[175] The energy sector is dominated by Russian companies. The largest power company Moldavskaya GRES (Cuciurgan power station) is in Dnestrovsc and owned by Inter RAO UES,[176] and the gas transmission and distribution company Tiraspoltransgaz is probably controlled by Gazprom, although Gazprom has not confirmed the ownership officially. The banking sector of Transnistria consists of 8 commercial banks, including Gazprombank. The oldest alcohol producer KVINT, located in Tiraspol, produces and exports brandy, wines and vodka.

Education

[edit]Transnistria has kept to the Russian educational standards, mainly using the Russian curriculum.[177]

Higher education diplomas issued by Transnistrian authorities are not recognised by most countries, resulting in graduates being unable to obtain well-paid jobs in Moldova or Western countries, leaving Russia as the default location for students and graduates.[177]

Human rights

[edit]The human rights record of the Transnistrian authorities has been criticised by several governments and international organisations.[which?] The 2007 Freedom in the World report, published by the U.S.-based Freedom House, described it as a "non-free" territory, having an equally bad situation in both political rights and civil liberties.[178]

According to a 2006 U.S. Department of State report:[179]

The right of citizens to change their government was restricted ... Authorities reportedly continued to use torture and arbitrary arrest and detention ... In Transnistria authorities limited freedom of speech and of the press ... Authorities usually did not permit free assembly ... In the separatist region of Transnistria the authorities continued to deny registration and harassed a number of minority religious groups ... The separatist region remained a significant source and transit area for trafficking in persons ...

LGBT rights

[edit]Transnistria does not recognize same-sex unions. The Code of Marriage and Family that came into force in 2002 states that marriage is a voluntary marital union between a man and a woman. The code does not recognize other types of partnership for both opposite-sex and same-sex couples other than marriage.[180]

Media

[edit]There is a regular mix of modern news media in Transnistria with a number of television stations, newspapers, and radio stations.

According to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) the media climate in Transnistria is restrictive and the authorities continue a long-standing campaign to silence independent opposition voices and groups.[181]

According to a US Department of State report for 2006, "Both of the region's major newspapers were controlled by the authorities. There was one independent weekly newspaper in Bender and another in the northern city of Rîbnița ... Separatist authorities harassed independent newspapers for critical reporting of the Transnistrian regime ... Most television and radio stations and print publication were controlled by Transnistrian authorities, which largely dictated their editorial policies and finance operations. Some broadcast networks, such as the TSV television station and the INTER-FM radio station, were owned by Transnistria's largest monopoly, Sheriff, which also holds a majority in the region's legislature ... In July 2005 the Transnistrian Supreme Council amended the election code to prohibit media controlled by the Transnistrian authorities from publishing results of polls and forecasts related to elections."[182]

Romanian-language schools

[edit]

Public education in the Romanian language (officially called Moldovan language in Transnistria) is done using the Soviet-originated Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet. The usage of the Latin script was restricted to only six schools. Four of these schools were forcibly closed by the authorities, for alleged refusal of the schools to apply for official accreditation.[183] These schools were later registered as private schools and reopened, a development which may have been accelerated by pressure from the European Union.[184]

The OSCE mission to Moldova has urged local authorities in the Transnistrian city of Rîbnița to return a confiscated building to the Moldovan Latin script school in the city. The unfinished building was nearing completion in 2004 when Transnistria took control of it during that year's school crisis.[185]

In November 2005 Ion Iovcev, the principal of a Romanian-language school in Transnistria and active advocate for human rights as well as a critic of the Transnistrian leadership, received threatening calls that he attributed to his criticism of the separatist regime.[182]

In August 2021, the Transnistrian government refused to register the Lucian Blaga High School at Tiraspol and forced it to suspend its activities for three months, which will affect the school year of the students of the school and constitutes a violation of several articles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[186]

Arms control and disarmament

[edit]Following the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the Russian 14th Army left 40,000 tons of weaponry and ammunition in Transnistria. In later years there were concerns[who?] that the Transnistrian authorities would try to sell these stocks internationally, and intense pressure was applied to have these removed by Russia.

In 2000 and 2001, Russia withdrew by rail 141 self-propelled artillery pieces and other armoured vehicles and locally destroyed 108 T-64 tanks and 139 other pieces of military equipment limited by the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE). During 2002 and 2003 Russian military officials destroyed a further 51 armoured vehicles, all of which were types not limited by the CFE Treaty. The OSCE also observed and verified the withdrawal of 48 trains with military equipment and ammunition in 2003. However, no further withdrawal activities have taken place since March 2004 and a further 20,000 tons of ammunition, as well as some remaining military equipment, are still to be removed.

In the autumn of 2006, the Transnistrian leadership agreed to let an OSCE inspectorate examine the munitions and further access was agreed moving forward.

Recent weapons inspections were permitted by Transnistria and conducted by the OSCE. The onus of responsibility rests on Russia to remove the rest of the supplies.

Transnistrian authorities declared that they are not involved in the manufacture or export of weapons. OSCE and European Union officials stated in 2005 that there is no evidence that Transnistria "has ever trafficked arms or nuclear material" and much of the alarm is due to the Moldovan government's attempts to pressure Transnistria.[187]

In 2007, foreign experts working on behalf of the United Nations said that the historically low levels of transparency and continued denial of full investigations to international monitors have reinforced negative perceptions of the Transnistrian government, although recent co-operation by Transnistrian authorities may have reflected a shift in the attitude of Transnistria.[188] Their report stated that the evidence for the illicit production and trafficking of weapons into and from Transnistria, has in the past been exaggerated, although the trafficking of light weapons is likely to have occurred before 2001 (the last year when export data showed US$900,000 worth of 'weapons, munitions, their parts and accessories' exported from Transnistria). The report also states that the same holds true for the production of such weapons, which is likely to have been carried out in the 1990s, primarily to equip Transnistrian forces.

The OSCE mission spokesman Claus Neukirch spoke about this situation: "There is often talk about sale of armaments from Transnistria, but there is no convincing evidence".[189]

In 2010, Viktor Kryzhanivsky, Ukraine's special envoy on Transnistria, stated that there was no ongoing arms or drug trafficking through the Transnistrian section of the Ukrainian-Moldovan border at the time.[190]

Sport

[edit]Transnistria is notable for being home to the Sheriff Tiraspol football club, which in 2021 became the first team representing Moldova to qualify for the UEFA Champions League group stage.[191] In 2022, UEFA blocked Sheriff from playing home games in Transnistria.[192]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Moldovan" (also spelt "Moldavian") is the official name in Transnistria for the language usually called "Romanian". It is written in the Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet, as opposed to the Romanian Latin alphabet.

- ^ Transnistria adopted a white-blue-red tricolor flag in 2017, which is almost identical to the flag of Russia[1] but with an aspect ratio of 1:2 instead of 2:3.

- ^ It is a matter of controversy whether Moldovans are the same as Romanians or a distinct ethnic group.

- ^ For other names, see the toponymy section

References

[edit]- ^ "В ПМР российский флаг разрешили использовать наравне с государственным" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 12 April 2017.

- ^ Smoltczyk, Alexander (24 April 2014). "Hopes Rise in Transnistria of a Russian Annexation". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

The breakaway region has its own military, its own constitution, a national anthem (called "We Sing the Praises of Transnistria") and a symphony orchestra which is known abroad.

- ^ "On the situation of Russian schools in Moldova". OSCE. 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Law of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic on the Functioning of Languages on the Territory of the Moldavian SSR". U.S. English Foundation Research. 2016. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Russian language in Moldova could lose their status (Русский язык в Молдове может потерять свой статус)". KORRESPONDENT. 6 April 2013.

- ^ The Supreme Soviet changed the official name of the republic from Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic to Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic on 5 November 1991. See: "Postanovlenie verkhovnogo soveta Pridnestrovskoi Moldavskoi Respubliki ob izmenenii nazvaniia respubliki", Dnestrovskaia pravda, 6 November 1991, 1.

- ^ "Peste 358 mii de locuitori din Regiunea Transnistreană dețin cetățenia Republicii Moldova și peste 367 mii figurează în registrul de stat al populației". www.gov.md/ro (in Romanian). Guvernul Republicii Moldova (Biroul Politici de Reintegrare). 17 April 2024. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Перепись населения ПМР [Population census of PMR]. newspmr.com (in Russian). 9 March 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Макроэкономика: Динамика и структура валового внутреннего продукта в 2021 году [Macroeconomics: Dynamics and structure of GDP in 2021] / Nr.2/249 - pg.3 (2022)" (PDF). www.cbpmr.net. Приднестровский Республиканский Банк [Pridnestrovian Republican Bank]. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Law No. 173 from 22 July 2005 "About main notes about special legal status of settlements of left bank of Dnestr (Transnistria)": Romanian Archived 15 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Russian Archived 15 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Moldova. territorial unit: Stinga Nistrului (Transnistria)". CIA World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Herd, Graeme P.; Moroney, Jennifer D. P. (2003). Security Dynamics in the Former Soviet Bloc. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29732-X.

- ^ Zielonka, Jan (2001). Democratic Consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924409-X.

- ^ "TRANSDNIESTRIAN CONFLICT" (PDF). State Department. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ Article 55 of the Constitution of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic

- ^ Jos Boonstra, Senior Researcher, Democratisation Programme, FRIDE. Moldova, Transnistria and European Democracy Policies Archived 8 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 2007

- ^ Hinteregger, Gerald; Heinrich, Hans-Georg (2004). Russia – Continuity and Change. Springer. p. 174. ISBN 3-211-22391-6.

- ^ Rosenstiel, Francis; Lejard, Edith; Boutsavath, Jean; Martz, Jacques (2002). Annuaire Europeen 2000/European Yearbook 2000. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-1844-6.

- ^ a b Bartmann, Barry; Tozun, Bahcheli (2004). De Facto States: The Quest for Sovereignty. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5476-0.

- ^ European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM) Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, November 2007

- ^ "Background – EU Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine". Eubam.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Der n-tv Atlas. Die Welt hinter den Nachrichten. Bertelsmann Lexicon Institute. 2008. page 31

- ^ "Education and Information – the golden passport for young Transnistrians". 26 September 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Transnistria: Russia's satellite state an open wound in Eastern Europe". Deutsche Welle. 28 May 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Vladimir Socor,"Frozen Conflicts in the Black Sea-South Caucasus Region". Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2014., IASPS Policy Briefings, 1 March 2004

- ^ Абхазия, Южная Осетия и Приднестровье признали независимость друг друга и призвали всех к этому же (in Russian). Newsru. 17 November 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ "Head of Foreign Ministry of the Republic of South Ossetia congratulated Minister of Foreign Affairs of the PMR with Sixth Anniversary of Creation of Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PMR. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Vichos, Ioannis F. "Moldova's Energy Strategy and the 'Frozen Conflict' of Transnistria". Ekemeuroenergy.org. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- ^ a b Necșuțu, Mădălin (16 March 2022). "Council of Europe Designates Transnistria 'Russian Occupied Territory'". balkaninsight.com. Balkan Insight. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Regions and territories: Trans-Dniester, BBC News, 7 March 2007

- ^ Breakaway Moldovan Region Of Transdniester Celebrates 30 Years Of 'Independence'

- ^ "The black hole that ate Moldova". The Economist. 3 May 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Лига русской молодежи: Антирусские речи Лари упоительны для румынских патриотов Бессарабии". Regnum. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "На похороны Леониды Лари правительство выделило 20 тысяч леев". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Новости: Молдова: Пусть у меня будут руки по локти в крови, но я вышвырну оккупантов, пришельцев и манкуртов за Днестр". Terra. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Пусть у меня будут руки по локти в крови, но я вышвырну оккупантов, пришельцев и манкуртов за Днестр". Retrieved 10 December 2021.[dead link]

- ^ "Рошка считает, что у его партии благородное и уважаемое прошлое". Retrieved 10 December 2021.[dead link]

- ^ ""Немного О "Героях" Или 20 Лет По Кругу" Печальные Итоги Молдавской Независимости". Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Regarding the basic provisions of the special legal status of the localities on the left side of the Dniester (Transnistria)". lex.justice.md/. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Union of Moldovans in Transnistria: We have no grounds to distrust Smirnov". Strategiya-pmr.ru. 7 December 2011. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Breakaway Moldovan Region Transnistria Bans Use of Name 'Transnistria'". 5 September 2024.

- ^ https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/separatist-region-of-moldova-banns-the-term-transnistria/

- ^ https://en.vspmr.org/news/supreme-council/zapret-naimenovaniya-transnistriya-.html

- ^ "Bessarabia region, Eastern Europe". Archived from the original on 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Map of Romania in 1941–1944". Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Dallin, Alexander (1957). "Romanization". Odessa, 1941–1944: A Case Study of Soviet Territory Under Foreign Rule. Center for Romanian Studies. pp. 87–90. ISBN 978-9739839112. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Romania and The Nazi-Soviet war, 1941–1944". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Casu, Igor. Stalinist terror in Soviet Moldova, by Igor Casu. Usm-md.academia.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Timeline: Moldova BBC Country Profile: Moldova

- ^ Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power, Anatol Lieven, Yale University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-300-07881-1, pp. 246

- ^ Can Liberal Pluralism Be Exported?, Will Kymlicka, Magdalena Opalski, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-924063-9, pp. 208

- ^ The painful past retold Social memory in Azerbaijan and Gagauzia, Hülya Demirdirek, Postkommunismens Antropologi, University of Copenhagen, 12–14 April 1996.

- ^ Andrei Panici. Romanian Nationalism in the Republic of Moldova, Global Review of Ethnopolitics, vol. 2 no. 2 (January 2003), pp. 37–51.

- ^ "Could Transnistria be the next Crimea?". Channel 4 News. 23 March 2014.

- ^ Hare, Paul (1999). "Who are the Moldovans?". In Paul Hare; Mohammed Ishaq; Judy Batt (eds.). Reconstituting the market: the political economy of microeconomic transformation. Taylor & Francis. pp. 363, 402. ISBN 90-5702-328-8. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ^ Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War, Stuart J. Kaufman, Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8014-8736-6, pp. 143

- ^ Kolsto, et al. "The Dniester Conflict: Between Irredentism and Separatism", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 45, No. 6 (1993): 108.

- ^ "Ukaz Prezidenta Soiuza Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik O Merakh po Normalizatsii Obstanovki v SSR Moldova", Sovetskaia Moldova, no. 295 (17249), 1990-12-23, 1.

- ^ "Postanovlenie verkhovnogo soveta Pridnestrovskoi Moldavskoi Respubliki ob izmenenii nazvaniia respubliki", Dnestrovskaia Pravda, 6 November 1991

- ^ "Приднестровский конфликт - серьёзная, нерешенная проблема Молдовы: Несколько хронологических данных о начале и эволюции войны". transnistria.md (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Бергман Вождь в чужой стае". femida-pmr.narod.ru.

- ^ Moldova Matters: Why Progress is Still Possible on Ukraine's Southwestern Flank, Pamela Hyde Smith, The Atlantic Council of the United States, March 2005

- ^ Netherlands Institute of International Relations – The OSCE Moldova and Russian diplomacy 2003 Archived 11 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine page 109

- ^ "Talk conditions of Transnistria on March 2011". Osw.waw.pl. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Popescu, Liliana (2013). "The futiliy of the negotiations on Transnistria". European Journal of Science and Theology. 9 (2): 115–126.

- ^ "Press releases and statements related to the 5+2 negotiations on the Transdniestrian settlement process". 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Transnistria wants to merge with Russia". Vestnik Kavkaza. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Moldova's Trans-Dniester region pleads to join Russia". Bbc.com. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Dniester public organizations ask Russia to consider possibility of Transnistria accession". En.itar-tass.com. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b Higgins, Andrew (28 February 2024). "A Breakaway Region of Moldova Asks Russia for Protection". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Grau, Lina (28 February 2024). "Moldova's Breakaway Region Appeals for Help From Russia". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ García-Ajofrín, Lola. "Transnistria tensions: Will Russia try to annex Moldova's breakaway region?". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Leven, Denis (28 February 2024). "Transnistria begs Putin to 'protect' it against Moldova". Politico. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Christian Edwards; Anna Chernova (10 January 2025). "A Russia-backed sliver of Moldova is fast running out of energy. Here's what to know". CNN. Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ "Moldova - 2.3 Road Network | Digital Logistics Capacity Assessments". lca.logcluster.org. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Roney, Anthony II (2023). "The Devil's Advocate: An Argument for Moldova and Ukraine to Seize Transnistria". Journal of Advanced Military Studies. 14 (2): 121–150. doi:10.21140/mcuj.20231402007. ISSN 2770-260X.

- ^ Trygve Kalland and Claus Neukirch, Moldovan Mission seeks solution to Dorotcaia's bitter harvest, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, 10 August 2005

- ^ (in Romanian) Locuitorii satului Vasilievca de pe malul stâng al Nistrului trăiesc clipe de coșmar, Deutsche Welle, 17 March 2005.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ CHISINAU overstates the number of Moldovan citizens living in Transnistria, MD: Press, 2006, archived from the original on 23 May 2013

- ^ 170,000 with citizenship Russia, Profvesti, 21 April 2013, archived from the original on 18 October 2015, retrieved 30 May 2013

- ^ Double citizenship Moldova and Romania in 2013, RU: Rosbalt, 2 April 2013

- ^ Romanian passport received 80 percent of Moldovans, MD: NBM

- ^ Radu, Alina (26 September 2019). "Education and Information – the golden passport for young Transnistrians". Foreign Policy Centre.

- ^ Double citizenship Moldova and Romania in 2013. Citizenship Russia or Ukraine in PMR, RU: Rosbalt, 2 April 2013

- ^ Transdniestrian Ukrainians will continue to vote in the territory of the Republic of Moldova, RU: NR2, archived from the original on 16 May 2013

- ^ "Transnistrian Militia Withdrew Its Posts from Vasilievca", Azi, MD, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 18 October 2006

- ^ John O'Loughlin, Vladimir Kolossov & Gerald Toal, "Inside the post-Soviet de facto states: a comparison of attitudes in Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria, in Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2015, p. 451.

- ^ Не з'явився на допит у СБУ. Україна оголосила у розшук "главу МЗС" Придністров'я

- ^ "PMR Supreme Council (Parliament of Transnistria's official website)". Vspmr.org. 17 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Moldova and the Dniestr Region: Contest Past, Frozen Present, Speculative Futures? Archived 9 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Herd, Graeme P., Conflict Studies Research Centre, 2005. Accessed 25 May 2007.

- ^ "Tiraspol not willing to register opposition representative in electoral race". Politicom.moldova.org. 21 November 2006. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Candidate to Office of Transnistrian Vice-President Comments on Opposition's Chances". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "US Department of State, Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Moldova – 2003". State.gov. 25 February 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Original Communism, Sorin Ozon, Romanian Center for Investigative Journalism, 13 July 2006.Accessed:31 October 2010. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Țăranu, A; Grecu, M. "The policy of linguistic cleansing in Transnistria". Archived from the original on 29 May 2006. Retrieved 30 March 2017., pp. 26–27. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ (in Russian) Министерство юстиции ПМР вынесло предупреждение общественному движению "Власть народу! За социальную справедливость!" и "Партии народовластия" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Ministry of Justice of PMR warned Power to the People movement and Narodovlastie party), Ольвия Пресс, 27–02–01.

- ^ Council Decision 2006/96/CFSP of 14 February 2006 implementing Common Position 2004/179/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine European Union Law – Official Journal. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Moldova". 26 October 2022.

- ^ "Transnistrian Communist Party leader released on probation". Transnistria.md. 26 September 2007. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ a b Moldova Strategic Conflict Assessment (SCA), Stuart Hensel, Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Moldova will hold referendum on EU membership without Transnistria: Sandu". 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Valeri Litskai: A situation based on pressure and threats cannot be considered favorable for the revival of contacts". Olvia.idknet.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Russia's humanitarian assistance is a planned propagandist action, Chișinău claims". Politicom.moldova.org. 23 March 2006. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Nezavisimaya Moldova", 25 October 1994; Informative Report of FAM of RM, nr.2, October 1994, pp. 5–6

- ^ Mihai Grecu, Anatol Țăranu, Trupele Ruse în Republica Moldova (Culegere de documente și materiale). Chișinău, 2004, p. 600.

- ^ "Interfax", Moscow, in Russian, 0850 gmt, 7 July 2004

- ^ Mihai Gribincea, "Russian troops in Transnistria – a threat to the security of the Republic of Moldova", Institute of Political and Military Studies, Chișinău, Moldova Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Russia continues to 'sustain the Dniestr region as a quasi-independent entity through direct and indirect means'

- ^ MC.DEL/21/04, 6 December 2004

- ^ Interfax. NATO must recognize Russia's compliance with Istanbul accords 14 July 2007. Retrieved 18 November 2007. Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kucera, Joshua (25 May 2015). "Russian Troops In Transnistria Squeezed By Ukraine And Moldova". Eurasianet. Open Society Foundations. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ iBi Center (18 November 2008). "NATO-resolution. 11. b". Nato-pa.int. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "McCain Backs Demand For Russian Troop Withdrawal From Transdniester". Rferl.org. 13 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Ukraine blocked Russian contingent to Transnistria (Moldova)". 22 May 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "With Russia Boxed In, Frozen Transdniester Conflict Could Heat Up". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. 31 May 2015.