Architecture of Limerick

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Limerick, like many other cities in Ireland, boasts a rich history of remarkable architecture. A document from 1574, prepared for the Spanish ambassador, provides a detailed description of the city's wealth and architectural features:

"Limerick is more formidable and aesthetically superior to all other cities in Ireland, with robust walls made of hewn marble. The city is accessible only by stone bridges, one of which features 14 arches, while the other has 8. The majority of the houses are constructed from square blocks of black marble, built in the form of towers and fortresses."

Several notable examples of this architectural heritage remain, including the 800-year-old St. Mary's Cathedral and King John's Castle.[1]

Ecclesiastical architecture

[edit]- St. Mary's Cathedral

St Mary's Cathedral the older of Limerick's two cathedrals, dates back to the 12th century. The cathedral features a blend of Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles, with Romanesque arches and doorways com plemented by Gothic windows. The plan and elevation of the cathedral reveal that its design has been altered and expanded over time. The original layout of the church followed the form of a Latin cross. Significant additions were made to the cathedral during the episcopate of Stephen Wall, Bishop of Limerick. The Romanesque doorway on the west side is an impressive display of intricate chevrons and decorative patterns. Like many medieval churches in Ireland, the building underwent substantial restoration during the Victorian era. The cathedral holds a dominant position in this medieval area of Limerick City, showcasing a harmonious blend of Romanesque and Gothic architectural influences.[2] The tower of St. Mary's Cathedral was added in the 14th century, and it rises to 120 feet

- St. John's Cathedral

The main body of St. John's Cathedral was designed by the English architect Philip Charles Hardwick, and constructed between 1856 and 1861. The cathedral features the tallest spire in Ireland, reaching a height of 94 meters, which was a later addition designed by M.A. Hennessy and completed in 1883. The exterior of St. John's Cathedral underwent a complete refurbishment in 2004, including new roofing and repointing of all stonework. Today, the cathedral stands as an imposing structure on an otherwise undeveloped side of the city center. Additionally, an important historical Protestant church, located near the cathedral, is currently in use by Dance Limerick, despite being in need of some repair.

- St. Munchin's Church, Englishtown

The newest St. Munchin’s Church (Church of Ireland) was built in 1827. It stands as a testament to Gothic architectural style, designed by George and James Pain. The church’s distinctive four pinnacles atop its tower give it a unique and distinguished appearance.

Located on King’s Island, between the Bishop’s Palace and the Villiers Alms Houses, St. Munchin’s Church has witnessed significant historical transformations. Built in 1827, it underwent renovation in 1980 by the Limerick Civic Trust. The building served as a venue for the Island Theatre Company for a period and is now used as a store for the Limerick Civic Trust.[3]

- St. John's Church, Irishtown

This freestanding double-height Romanesque limestone church, built in 1851 on the site of a medieval church, features a gabled west elevation with a central Romanesque portal, a blind arcade of three round arches at first-floor level, and a rose window above. A three-stage square-plan tower at the southwest corner supports a splay-foot pyramidal spire with decorative detailing. The church has an apsidal east end and sacristy to the northeast. Its north and south elevations comprise four-bay single-storey aisles with clerestorey oculi, articulated by shallow piers. Roofs are natural slate, with cast-iron rainwater goods and a decorative limestone chimneystack.

Walls are squared and snecked tooled limestone ashlar with smooth ashlar dressings, including plinth, sill, eaves courses, and copings. Windows include single and paired round-arched openings and oculi, with leaded and plain glazing, mostly added c. 1980 and protected by metal grilles. The nave features arcades with octagonal columns and cushion capitals, and an original A-frame roof with some replaced rafters. Interior modifications include a new timber floor, c. 2004. The church is located on an island site with historic tombs and grave markers, enclosed by a rubble boundary wall, partially rebuilt or altered, with the eastern section recently demolished.[4]

- Franciscan Church, Henry Street

The Franciscan Church on Lower Henry Street, Limerick, stands on the site of an earlier 1820s chapel. The foundation stone for the current structure was laid in May 1876 by Dr. Butler, Bishop of Limerick. Construction was carried out by builders McCarthy and Guerin, under the direction of architect William Corbett, and completed in 1886. The church is noted for its neo-classical architectural style, featuring an imposing limestone portico supported by four large pillars, an entablature, and a pediment topped with statues of Saint Francis, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Saint Anthony.

The interior includes granite pillars, a clerestory with triple round-headed windows, and Latin hymn inscriptions. Notable features include stained glass windows depicting Saint Bernardine of Siena, Saint Louis of France, and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, along with a painting illustrating scenes from the life of Saint Francis of Assisi.

The Franciscan presence in Limerick dates back to the 13th century, when Thomas de Burgo founded a friary near Sir Harry’s Mall. This original monastery, Saint Francis Abbey, influenced local names such as Abbey River. The friars were displaced in 1651 during the Cromwellian conquest but returned and later relocated to Newgate Lane in 1782, a site now occupied by the Limerick Museum.[5]

- Sacred Heart Church, The Crescent

Designed by William Corbett, the church dates back to 1832. Built in the classical style, its facade serves as a central feature of The Crescent area in Georgian Limerick. The church's exceptionally fine classical interior, crafted with a wealth of high-quality materials and skilled craftsmanship, further enhances the architectural significance of this ecclesiastical site.[6]

- St Saviour's Church (Dominicans)

The existing church on Glentworth Street was constructed in 1815 under the leadership of Fr. Joseph Harrigan, on land donated by Edward Henry, the Earl of Limerick. It replaced an earlier church located on Fish Lane. In 1973, it was elevated to the status of a parish church. The church underwent renovations in the 1860s, carried out by the architect John Wallace. Additionally, the priory was built in 1943.

Medieval Limerick

[edit]

The medieval city of Limerick is primarily concentrated in the southern section of Kings Island, known as Englishtown, and to the south of the Abbey River in an area called Irishtown, just to the north of the present-day city center. This area is home to some of Limerick's most significant historical attractions, including King John's Castle , which was completed around 1200. The castle’s walls, towers, and fortifications still stand today. Additionally, the remains of a Viking settlement were uncovered during the construction of the visitor center at the site. St. Mary's Cathedral, founded in 1168, is the oldest recorded building in Limerick. It was constructed on the site of an earlier castle belonging to the King of Munster. Nicholas Street and Mary Street, the medieval heart of Limerick, once featured many examples of medieval buildings, including tall gabled houses in the Flemish or Dutch style. Unfortunately, very little, if any, of this historic streetscape remains today. Following the development of Newtown Pery, this area of the city experienced a period of decline.[7] Today both the Englishtown and Irishtown areas remain neglected and dilapidated in appearance.

Castle Lane beside King Johns Castle includes a reconstruction of some medieval buildings including a granary, labourers cottage, and gabled houses. The development is mainly for tourism purposes.

Georgian architecture

[edit]

Georgian architecture began to make a significant appearance in Limerick around the 1800s. While some buildings have since been demolished, much of the city center is still constructed in the Georgian style. One notable example is John's Square, located in front of St. John’s Cathedral, leading towards the city center. Stone-faced Georgian offices and townhouses were deliberately built around this square.

The development of Georgian Limerick was largely driven by Edmund Sexton Pery,, the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons, whose influence is reflected in the city's name—Newtown Pery—preserved in the Georgian city center. This expansion extended the city south of the Abbey River, replacing much of the medieval city's original structures. During this period, most of the walls of the medieval city were dismantled to allow for the city's growth.

Newtown Pery was designed entirely in the Georgian style, characterized by long, wide, and elegant streets arranged in a grid plan, with O'Connell Street (formerly Georges Street) at its core. The creation of this new town marked the shift of Limerick's economic and cultural center, as the medieval city, along with its main thoroughfare, Nicholas Street, declined. Today, much of the Georgian architecture remains intact, with areas like the Crescent along O'Connell Street and Pery Square standing as some of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in Ireland. A publicly accessible example of Georgian architecture is the People's Museum of Limerick, located at Pery Square.

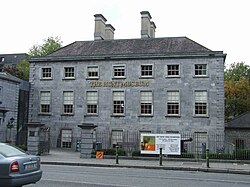

The Hunt Museum

The Hunt Museum is housed in the historic 18th-century former Custom House. Established to showcase a collection of approximately 2,000 works of art and antiquities, the museum was founded by John and Gertrude Hunt, who amassed the collection throughout their lives.[8]

Victorian and Edwardian architecture

[edit]From the 19th century onward, much Victorian and Edwardian architecture became prominent in Limerick. Unified terraces, as well as detached and semi-detached dwellings, were constructed by the middle class along roads extending from the city center. These developments are still visible today in areas such as O'Connell Avenue, the South and North Circular Roads, Ennis Road, Shelbourne Road, and Mulgrave Street.

Typical features of Victorian and Edwardian architecture in Limerick include arched or bay windows with intricate brick detailing around doorways, as well as elaborate railings enclosing long front gardens. Buildings from the Edwardian period also often feature balconies, porched and timbered gables, and horizontal mullioned windows, further contributing to the distinctive architectural style of the time.[9]

20th century

[edit]

FromFrom the period of Irish Independence up until the 1960s, Limerick experienced minimal development. Housing became a significant issue, as many of the city's poorer residents lived in overcrowded slums, streets, and laneways in the oldest parts of the city. The conditions in these areas during the early 20th century are vividly depicted in the internationally bestselling memoir Angela’s Ashes, written by Frank McCourt..

In the 1960s, Limerick Corporation began clearing these slums and laneways, relocating families to new, large council estates on the outskirts of the city. These estates were primarily constructed in areas such as Moyross, Southill, the Island Field (St. Mary’s Park), and Ballinacurra Weston. Initially, the estates were seen as a success, but over time, they faced challenges, including high levels of disadvantage, unemployment, poverty, and crime—issues that were also observed in other parts of Ireland, such as Ballymun.

However, since the early 21st century, Limerick's inner-city areas have undergone regeneration and revitalization, supported by funding and development from both the City and County Council, as well as the Government. One notable development in the early 1990s was the creation of Arthur's Quay Park, which was built on the site of a surface car park as part of a plan to establish a pedestrian route along the waterfront. Designed by Murray Ó Laoire Architects, the park incorporated a tourist information office and was awarded the RIAI Triennial Gold Medal for 1989–1991.[10]

During this period, the city of Limerick expanded significantly, with substantial development occurring outside the city boundary, resulting in the creation of new suburban areas. One of the most notable developments was the establishment of the University of Limerickin the suburb of Castletroy, located towards the eastern edge of the city. UL is home to the University Concert Hall, a 1,000-seat venue that hosts a wide range of events. The UL Arena, which opened in 2002, is Ireland’s largest indoor sports complex. It includes the National 50m Swimming Pool, the only water facility in Ireland approved by FINA, the international swimming body, and built to Olympic standards. The Arena also houses an Indoor Sports Hall with 3,600 square meters of space, featuring four wood-sprung courts for various sports, a sprint track, an international 400m athletics track, and a 200m three-lane suspended jogging track. Additionally, the facility includes a state-of-the-art cardiovascular and strength training center, a weight-training room, team rooms, an aerobics studio, and classroom areas. The Arena is frequently used by the Munster rugby team.

On the south side of the city, the Crescent Shopping Centre, the largest shopping center in Ireland outside of Dublin, was developed in the suburb of Dooradoyle Spanning 100,000 square meters of retail space and housing over 90 shops, it became a major commercial hub.

By the end of the 20th century and into the early 21st century, Limerick experienced a continued trend toward suburbanization, raising concerns regarding the development patterns of the city, particularly the proliferation of out-of-town retail developments that diminished footfall in the city center. In response to these concerns, since the early 2010s, significant efforts have been made to boost foot traffic in the city center and curb ongoing suburbanization. These initiatives have included street facelifts, community events organized by the council, and restrictions on the development of retail spaces outside the city center and city boundaries. A prominent example of this revitalization effort is the Crescent Shopping Centre.[11]

Bridges

[edit]As a city located along the Shannon and at a key crossing point, Limerick's bridges play a crucial role in the region's connectivity. These bridges link the northern bank of the river, and County Clare, to the southern bank, which is part of County Limerick. In addition to being integral to the Limerick to Galway route, these crossings are essential for connecting Shannon Airport to the city and facilitating travel to other parts of the region and beyond.

Thomond Bridge

[edit]

The earliest bridge in Limerick, Thomond Bridge,, was constructed near a fording point and played a significant role in the city's history. It was notably the site of a failed defense during the Siege of Limerick.. At one end of the bridge stands the Treaty Stone,, which symbolizes the signing of the Treaty of Limerick. It is believed that the treaty itself was signed in a campaign tent. The current structure of Thomond Bridge was completed in 1836, replacing the earlier bridge, which was located next to King John's Castle. Today, the bridge forms part of the R445 (formerly N7), serving as a vital crossing on the Northern Relief Road and facilitating traffic flow.[12]

Sarsfield Bridge

[edit]The second River Shannon crossing in Limerick, now known as Sarsfield Bridge, commemorates Patrick Sarsfield, the Earl of Lucan, renowned for his role in the Williamite War and particularly the 1691 Siege of Limerick and the Treaty of Limerick. Originally opened as Wellesley Bridge on 5 August 1835 after 11 years of construction, it was designed by the Scottish engineer Alexander Nimmo, inspired by the Pont de Neuilly in Paris. The bridge was a key development for the city, facilitating expansion to the northern shore of the river.

The structure consists of five large and elegant elliptical arches with an open balustrade, spanning from a man-made island (originally known as Wellesley Pier, now called Shannon Island) to the northern shore. A simple flat, swivel deck with iron lattice railings crosses a canal and road from the island to what was once Brunswick Street, now Sarsfield Street. Although the swivel end of the bridge is no longer operational, its heavy machinery remains intact underneath the roadway. A lock system has replaced the swivel section to allow passage for smaller boats. Despite these modifications, the bridge has largely retained its original design, including the original lamp standards.[13]

Rowing clubhouses are situated on Shannon Island, flanking either side of Sarsfield Bridge. The Shannon Rowing Club, founded by Sir Peter Tait in 1866, boasts an elegant clubhouse on the northern side of the bridge. On the southern side, the Limerick Boat Club, established in 1870, occupies a more modest structure. Both clubs have long histories tied to the river and play an important role in the city's rowing community.[14]

A monument by sculptor James Power , located on Sarsfield Bridge just above the Limerick Boat Club building, commemorates the1916 Rising. Prior to this, an earlier monument stood on the same site, featuring a statue of Viscount Fitzgibbon of Mountshannon House,[15]who was killed during The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclavain 1854. The statue was flanked by two Russian cannons captured during the Crimean War. This monument was destroyed by the Irish Republican Army in 1930.[16] At the northern end of the bridge, another memorial marks the War of Independence. It commemorates two former mayors of Limerick, George Clancyand Michael O'Callaghan, along with others who were killed by British forces in 1921. In their honor, the quays on the northern shore are named Clancy Strand and O'Callaghan Strand.

Shannon Bridge

[edit]

The Shannon Bridge is the most recent River Shannon crossing in Limerick city centre. Completed in the late 1980s, it officially opened on 30 May 1988. The bridge links to a relief road that passes through a bird sanctuary and runs around the northern edge of the city. While it is sometimes still referred to as "The New Bridge," it is noteworthy that the Abbey Bridge, crossing the Abbey River, is actually the newer of the two. For a time after its construction, the bridge was also known as "The Whistling Bridge" due to the resonating sound produced by the fencing when winds from the Shannon Estuary passed through. In periods of strong winds, the resulting whistling was notably loud. However, the issue was eventually addressed by adding simple grills, which eliminated the sound.[17]

Baal's Bridge

[edit]This bridge is one of the oldest in the city. The current structure, built between 1830 and 1831, is a single-arched, hump-back limestone bridge. It replaced an earlier four-arched bridge that served as the only crossing over the Abbey River between Englishtown and Irishtown before the mid-18th century.[18] Early drawings of the bridge show a row of houses on it before it was replaced. During the construction of the new bridge in 1830, a significant archaeological discovery was made in the foundations of the old bridge. A brass Square of Freemasonry , inscribed with the date 1507, was found. The square also bears the inscription: "I will strive to live with love and care upon the level, by the square." This artifact is reputed to be one of the earliest Masonic items ever discovered in the world.[19]

Other bridges and the tunnel

[edit]The bridge at the northern end of King's Island connects to Corbally on the north side of the city. This is a simpler bridge, positioned further up the Shannon. The only other road bridge across the Shannon near the city is the "University Bridge," which opened in 2004. The bridge was officially opened by then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern and serves as a modern connection between the recently developed north bank campus of the University of Limerick, which includes student accommodation and the Health Science building, and the main southern campus. However, it does not function as a public crossing, as there is no direct access from the Clare side.

Additionally, the University of Limerick is home to one of the longest footbridges in Europe, known as TThe Living Bridge This bridge is a significant architectural feature on the campus, offering pedestrian access across the Shannon River.[20][21]

Another bridge is named after Dr. Sylvester O'Halloran, which opened in 1987.

The Limerick Tunnel opened in July 2010 as part of the Limerick Southern Road. The tunnel forms a fourth river crossing of the Shannon. It is a 675m long,[22] twin-bore road tunnel underneath the River Shannon on the outskirts of the city.

Architecture lost and found

[edit]

The primary streets in the city centre were originally lined with predominantly uniform Georgian townhouses. However, there are instances where modern architectural styles have been fused with Georgian elements within individual buildings. A notable example of controversial demolition occurred in May 1891[23], when the Cruises Hotel, the oldest hotel in Limerick and a place where Daniel O'Connell had once stayed, was demolished in 1990 to make way for the construction of the Cruises Street pedestrian area, which opened in 1992. Today, the site of the former Cruises Hotel is occupied by a Costa Coffee shop at the right-hand corner of the street entrance. Other examples of lost architectural heritage include the facade of the old Cannock's Department Store (now Penney's), which was demolished in the 1960s and replaced with a more modern structure. Nevertheless, the iconic clock atop the building has remained and underwent a significant restoration project in 2024. [24] Similarly, the facade of Todd's Department Store (now Brown Thomas), which was destroyed by a fire in the late 1950s, has been replaced with a more contemporary design.

Since 1990, Ireland has implemented the Local Government (Planning and Development) Regulations, which introduced the requirement for Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA). These regulations stipulate that certain categories of development projects must submit an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) when applying for planning permission. The EIS is intended to evaluate the potential environmental impacts of the proposed development, ensuring that the potential effects on the environment are carefully considered before approval is granted. This regulation aims to promote sustainable development by identifying and addressing any significant adverse effects on the environment that may result from the development process.[25] Examples of restoration and adaptive reuse in Limerick include the conversion of historic bank buildings into pub and the transformation of old stone-built warehouses, with some Georgian townhouses being repurposed as up-market apartments. These refurbishments often involve cleaning brickwork, installing replica railings outside sash windows with brass catches, and adding new, historically accurate street railings. Several areas of the city have benefited from significant restoration projects, particularly on Mallow Street, Catherine Street, The Crescent, and the historical areas of King's Island, which have seen notable improvements in the 21st century. Additionally, [26] King John's castle underwent a redevelopment between 2011 and 2013, transforming it into a major tourist attraction for the city.

Modern architecture

[edit]

Although a lot of developments in Limerick were concentrated in suburban areas of the city in the early 21st century, there has been notable modern architectural developments and improvements in the appearance of city centre in recent years. Most developments have been along the banks of the river Shannon and are facing onto the river. The most prominent are the 60m high Riverpoint building designed by Burke Kennedy Doyle Architects and completed in 2008 and the 200 ft four-star Clayton Hotel on Steamboat Quay, designed by Limerick firm Murray Ó Laoire Architects and completed in 2002. Other developments include apartments and office blocks along the quay's and in areas such as Mount Kenneth Place, Harvey's Quay, Lower Cecil Street and Steamboat Quay. Other developments in the city centre include the successful redevelopment of Bedford Row, Henry Street, Thomas Street and Catherine Street.

In 2007, Thomond Park underwent a redevelopment project which included the construction of two large stands to accommodate a capacity attendance of 26,500 with 15,100 seated. The stadium has become an icon for Limerick City and in 2009, the design of the stadium, by Murray Ó Laoire Architects, won the people's choice award from the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland. In 2023, a new International Rugby Experience attraction, built on the corner of O'Connell Street and Cecil Street in the city centre, opened to the public. The building's architecture is built based on the neighbouring Georgian architecture on O'Connell Street. The JP McManus charitable foundation donated €30 million for the building's development.[27] The foundation offered the building to Limerick City and County Council in April 2024, however the council announced in October 2024 that after "extensive due diligence" they would not be able to cover the operational and funding cost of the faculty.[28][29] The building, designed by Niall McLaughlin Architects, was crowned 'Ireland's Favourite Building' in 2023 by the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland through the Public Choice awards.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Stalley, Roger (3 August 2020). Brown, Sarah; Stalley, Roger (eds.). Limerick and South-West Ireland: Medieval Art and Architecture (1 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003077206. ISBN 978-1-003-07720-6.

- ^ FUSIO. "Saint Mary's Church of Ireland Cathedral, Nicholas Street, Athlunkard Street, LIMERICK MUNICIPAL BOROUGH, Limerick, LIMERICK". Buildings of Ireland. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "St. Munchin's Church - Church of Ireland • Churches". 23 October 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ FUSIO. "Saint John's Church, John's Square, Church Street, Limerick, LIMERICK". Buildings of Ireland. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ "Franciscan Church in Limerick, Ireland". GPSmyCity. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ "Church of the Sacred Heart, the Crescent, LIMERICK MUNICIPAL BOROUGH, Limerick, LIMERICK". Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland pg505

- ^ "Our History". The Hunt Museum. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ "Buildings of Ireland: National Inventory of Architectural Heritage". Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ https://www.neverlookback.eva.ie/locations/former-tourist-office-arthurs-quay?origin=serp_auto

- ^ Hurley, David (20 October 2020). "New plan targets Limerick shopping centre – no new floorspace will be allowed at the Crescent". limerickleader.ie. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ "Thomond Bridge". film.limerick.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Spellissy, S., The History of Limerick City, Celtic Bookshop, Limerick, 1998. p.295.

- ^ Spellissy, p.242

- ^ "Limerick's Link to the Crimean War, Liam O'Brien • Guest Posts". 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Spellissy, p.297.

- ^ "Limerick Bridges • Limerick Places". 19 July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Baal's Bridge, Mary Street, Broad Street, LIMERICK MUNICIPAL BOROUGH, Limerick, LIMERICK". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Baal's Bridge Square". Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Arup wins award for Living Bridge". irishconstruction.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "LM085 Bachelor of Engineering in Civil Engineering". University of Limerick. Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ "Direct Route". Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Slater, Sharon (17 June 2023). "From Parnell to Senator Kennedy: Remembering the famous faces who visited Cruise's Royal Hotel". Limerick Post Newspaper. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Rabbitts, Nick (25 March 2024). "'Penneys' from heaven as landmark Limerick clock being repaired". limerickleader.ie. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ Book (eISB), electronic Irish Statute. "electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB)". www.irishstatutebook.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Society, Irish Georgian. ">About Us". IGS Craft (en-IE). Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Halloran, Cathy (3 May 2023). "International Rugby Experience opens in Limerick". RTÉ News.

- ^ O'Donovan, Katie (16 April 2024). "International Rugby Experience to be gifted to people of Limerick". Limerick Post Newspaper. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ http://www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2024/1024/1477352-rugby-experience-limerick/

- ^ "International Rugby Experience is crowned Ireland's favourite building at architecture awards". Irish Independent. 23 June 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Shannonside sells itself as Europe's new Riverside City Wednesday, 10 November 2004 The Irish Times